Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch

“Oh, for looking at the Promised Land!”

A perennial

theme, selling the farm to be “richer’n

mud.”

“Men are

such mysteries to me.”

“Well,

it’s time you got one of your own, and learned about ‘em firsthand.”

“Well, land

o’ goodness, if it ain’t just like one o’ them fairy stories

where the fellow rubs the lamp and the thieves jumps out of the jars and brings

him the magic carpet that flies, so as he can go high-kitin’

through the air like a witch on a broomstick, and drop down anyplace he

pleases.”

“Morpheus must have tempted me. Grand old Morphy.”

“Beard of

the Prophet! Madam, WILL YOU MARRY ME?!?”

“Shhhhh! He thunk himself to

sleep.”

Andre Sennwald of the New

York Times got sufficiently puffed up to write of it as “a genuinely

amusing carnival for this disrespectful year of grace,” two days before

Halloween of 1934. Leonard Maltin, “venerable

melodrama...” Hal Erickson (All

Movie Guide), who wouldn’t be caught dead in one, pooh-poohs it

copiously as “ploddingly paced... hoary old... novel about how wonderful

it is to be poor.” Otis Ferguson was of that very mind, cited in Halliwell’s Film Guide in

accordance with its view down a long, pointed nose at Chaplin’s

“never-never milieu” and other gratuitous notions.

Strike Me Pink

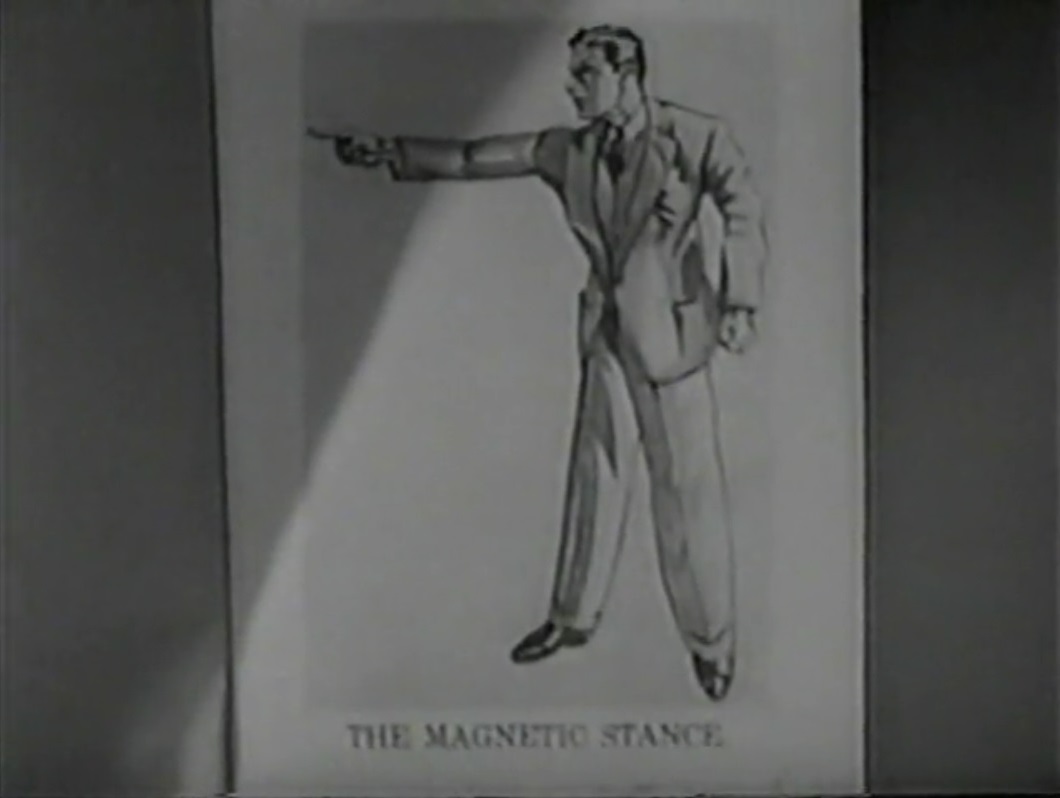

“Follow all

these simple instructions, and you will become a fearless leader.”

Truffaut takes

stock of this in Tirez sur le pianiste, absolutely. Here it’s a question of

college bullies hectoring an industrious townie, rapidly metamorphosing into

Dreamland Park menaced by a gang of vicious hoodlums.

“You see,

our company is going to put a number of little amusement machines in the park,

to educate the great American public.” The entre-deux-guerres. A phony

murder scene, a real damsel (“I get it, huh-huh-huh”) in phony

distress... Keaton’s ghostly card game (“Pete? He looks exactly like Joe!”) described by Alan

Schneider... Parkyakarkus takes on the mission impossible of spiking the

one-armed bandits (cf. “Wheels”,

dir. Tom Gries for the series)... the gang knock out the cops and take their

uniforms... the real hoodoo.

The furious

finale is solus

Cantor on the rollercoaster chased by faux cops, then midget racer, balloon-and-fireworks,

parachute, trapeze act and Chinese mandarin, the George Formby formula to

perfection.

The wizard Taurog

is with comedy brings in Gregg Toland for the musical

numbers (Merritt Gerstad elsewhere), Goldwyn’s

idea of an entertainment more than entertaining, and the director’s

precision with the mobsters (Brian Donlevy, William Frawley, Jack LaRue, Edward Brophy et

al.) is rare as rare.

Neil

Simon’s finger (The Sunshine Boys),

Eric Von Zipper’s finger, the original of Rod Serling’s “Mr.

Denton on Doomsday” (dir. Allen Reisner for The Twilight Zone), The Goldwyn Girls,

Ethel Merman, the immortal pitchman, Sunnie

O’Dea (her reflection in the glossy black nightclub floor comes as a

surprise to her), the formidable Sally Eilers,

Parkyakarkus, Rita Rio as Mademoiselle Fifi, and Eddie Cantor (looking in

fright like the original Robert Middleton) as Edward “Killer” Pink,

park manager.

Even the curious

“cricket” gag in The Longest

Day (dirs. Annakin-Marton-Wicki). Harold Arlen

& Lew Brown, Robert Alton, Richard Day, Omar Kiam,

by top writers of comedy, from the author of Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Sedgwick’s Speak Easily... a film perfectly of its time, but after the war it will be seen to come

into its own, in between probably the inspiration for Chaplin’s The Great Dictator... when something bo-thers

you, do like the bron-cos do, they bump-ty bump and shoo trouble away...

Frank S. Nugent

of the New York Times saw “a

case of mistaken identity” in Cantor for Lloyd (cp. Why Worry?, dirs. Fred Newmeyer & Sam

Taylor) and was disappointed (he refers to the producer nevertheless as

“the Ziegfeld of the Pacific”). Variety,

“Cantor is aces all the way.” TV Guide,

“brisk songs, decent dialog.” Catholic News Service Media Review

Office, “weak... lackluster”. Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “harmless enough,

I guess.” Mark Deming (All Movie

Guide), “well suited to his talents.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “acceptable”, citing more

Variety, “the take will be big.”

Boys Town

Taurog’s

resources are extremely rich. By this point his precise geometry relies almost

not at all on his thematic material, so his liquidity of comic stuff moves very

easily in or out of every situation. Without attachments, his dissolving poetic

is a wavering film that goes successfully into surrealism without any

difficulties. The democratic element appears reflected in the sharp cutting on

a collapsible grid, or expanding.

Presenting Lily Mars

A highly detailed

scenario is matched by the settings to give a thoroughly informative view of

the young artiste. Her late father was a piano tuner, her mother makes hats,

one of her siblings is a great collector of doorknobs.

Midhaven, Indiana, home of a successful New York producer

visiting his mother and introduced to the girl.

The honeymoon of

a Russian princess is depicted in the upcoming show, Let Me Dream. Lily

sends up the soprano at a Gotham nightclub where Bob Crosby leads the band, she

gets the part, too young and inexperienced. The soprano is back for opening

night, Lily’s a chambermaid. The next show is just for her.

Prof.

Eggleston’s Lessons in Acting (“Horror”, hands

upraised, mouth open) is the Bible of the trainee, her Lady Macbeth is a

helpless iteration of come to bed. She plies the producer with The

Secret Bride forsaken holding a daughter outside his window.

An old trouper on

the New York stage helps her out in the duet, “every little movement has

a meaning...”

Garland sings,

hoofs with Tommy Dorsey, and is a regular Jules Munshin

with comedy. Marta Eggerth’s brilliant soprano

earns this offstage remark, “she’s always gettin’

hurty-turty”.

Onionhead

A vast comedy on

the price of onions. The centerpoint is a haughty

Coast Guard ensign who just before and at the start of the war pilfers half the

mess funds every month from the buoy tender on which he serves, starving the

crew but pampering the oblivious captain, an otherwise diligent officer, to

cover the theft.

The hero’s

long education begins at college, continues at boot camp and aboard ship, and

is partly sentimental. He is a mirror to the ensign, always failing with girls

because he stints them. He is a Cook’s Mate Third Class.

The voluminous

expression of the theme takes in many a succession of finer points, in scenes

and sequences each so perfectly constructed as to concentrate interest in

itself. The proper treatment is surrealistic, the scale of the writing and

filming allows this within fair bounds of realism, just as it admits with no

effort an allusion to Capra’s It’s

a Wonderful Life, or even a great examination of Blystone’s Great Guy (a tale of Weights &

Measures defending the housewife).

So, above all, a

metaphor of the war.

His girl cites

Twain at him, but the hero sizes up the situation on his own, “I was a

worse son than he was a father,” in a tone of voice that suggests

incredulity.

Visit to a Small Planet

An absolute

satire, part science-fiction classic and part A King in New York.

The visitor from

X47 is a boob, but the Virginians he meets are still more so. The hopeless

situation is finally abandoned, he returns to his planet.

Much of the

material, such as the bebop beatnik bar and the Earthling romance, goes into The Nutty Professor.

College kids,

hipsters, TV commentators and executives, civil defense wardens, local sheriffs

and guardsmen, all come in for the portrait, even the daffy homemaker who takes

it all in stride.

Sergeant Dead Head

Taurog began his

work by writing and directing with Larry Semon, in

this instance the influence of Keaton is decisive.

One of the

greatest comedies ever made by Keaton is not signed by him (cf. Le Roi des Champs-Élysées), and he acts only in a few

scenes.

An Air Force

Sergeant hides aboard Hercules III to avoid his commanding officer, it is

launched with a chimpanzee for “Project Moon Monkey”, a test of

observed personality changes after space flight. The hapless sergeant becomes a

hero, a ladies’ man and a thorn in the side of the brass. A double is

found in the ranks to replace him and marry his girl, for the benefit of the

press.

This is very much

a sound comedy, a musical, even. Slapstick is rendered by Keaton himself early

on in a basic sense with piano accompaniment, the virtuoso treatment of the

fire-hose gag belies this as the dry nozzle suddenly douses his face and one

leg goes up as if the kickoff were underway, he topples over. WAAFs are drilled but do not hear his command, they march

right over him.

The visual

language is extensive and scenic, Sgt. Deadhead (Frankie Avalon) sits on Gen. Fogg’s newly-installed desktop panic button, red

alert is sounded, WAAFs run out in towels, stand to

attention as Navy and Royal Navy brass drive onto the base, the girls must

salute, their towels fall.

Lt. Kinsey (Eve

Arden) later sings her great number, “You Should Have Seen the One That

Got Away”, around the WAAF barracks, where girls in showers briefly serve

as chorus.

But the fineness

of the satire extends to the whole structural characterization of sober

military types as essentially mad, and this is especially striking in Gale

Gordon’s performance as a Navy psychiatrist quite professionally bonkers.

There is no point of reference, no straight man except Cesar Romero as an

admiral whose sea legs in all this are a simulacrum of sobriety, to conceal his

craftiness.

The comic center,

the whole note of madness per se is the honeymoon couple, who sing

“Let’s Play Love” very happily.

Sgt.

Deadhead’s Whoosher Bomb Rocket fails on the

base lawn, “you light its tail and—” it explodes in his face.

Gen. Fogg’s project is epochal. “Rufus,” says Lt. Kinsey, “after

today your name is going down in the history books, I feel sure.” He

(Fred Clark) tells her in reply, “I’ll share my glory with you, my

dear.”

Pat Buttram is

the President, he tries on the space helmet brought by the young couple as a

gift and is temporarily detained by White House Marines as the real Sgt. O.K.

Deadhead.

The bride and

groom escape to a helicopter on the lawn, where they embrace and send it up

unawares.

Deadhead in space

turns to the chimp, he feels the effect and sternly commands, “give me

that banana!”

The comedy

switcheroo in the honeymoon suite has the bride, Cpl. Lucy Turner (Deborah Walley), serenade the reluctant doppelgänger

delightedly, then be gratified when the switch is on again and her husband

takes up the refrain.

The monumentality

of the scene is enforced by repeated interruptions from the marching brass in

dress uniforms at the door to right the wronged impostor.

“That idiot

Deadhead has made a mockery of my entire career,” says the chimp in

rapid, harmonious tones to a TV reporter. “Someone made a bloomer,”

the Royal Navy malapropizes.

The Navy

psychiatrist recommends the double, “he’s patriotic.” The

other brass are alarmed, “patriotic?” The captain explains,

“he’ll do exactly as he’s told, after I hypnotize him.”

He later ventures this at a critical moment, rising from his seat and drawing

out his pocket watch to practice. The motion is not carried. How far must the

impostor go? “As far as you have to,” Lt. Kinsey says, “for

your country.”

And there is the

secondary theme of McAvoy (Harvey Lembeck)

in the guardhouse, he has exploding pens for escape, Deadhead is incarcerated

after the panic button mistake, McAvoy goes back

inside seeing how Gen. Fogg has it in for the

sergeant, and he is still there when all the brass and Fogg

and Kinsey are locked up at last.

Deadhead’s

flight is given out by the admiral as “not an error, a well-planned

secret launch with a brave, heroic volunteer, he’ll get a medal, even

Gen. Fogg will get a medal.”

Which puts Sgt.

and Mrs. O.K. Deadhead ever so briefly in the White House.

The news anchor

covering the flight and splashdown keeps getting a news flash slipped to him by

the crew on the set or in the newsroom, “zookeepers acclaim moon

monkey.”

Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini

Machine

Five years after The

1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, Ellwood Ullman and

Robert Kaufman join forces to create this meditation for Norman Taurog by way

of Goldfinger. He of the auric Persian

slippers is a wealthy mortician and proprietor of Goldfoot

Memorial Park, his machine makes beautiful robots to lure the world’s

wealthy into marriage and transfer all to him.

No. 11, Diane, is

accidentally shot full of holes by bank robbers as she walks along the

sidewalk, milk pours out of her when she drinks, no other harm is done except

that she vamps the wrong guy, Craig Gamble of Secret Intelligence Command,

instead of richest and most eligible bachelor Todd Armstrong.

The mistake is

quickly put to rights, Diane is sent out once again. The girls are merely toys

for the doctor, he gives each one a computer education to supplement her

allurements, No. 12 soaks up art appreciation before meeting Pardo Perez, the wealthy Spanish painter. Dr. Goldfoot’s assistant Igor invents an attaché case

with a secret weapon, a boxing glove and arm spring up to bop you. Dr. Goldfoot sees all on his monitors (a painting represents

his own earlier invention, a three-eyed girl).

Gamble (Agent

00½) and Armstrong investigate, are captured and escape through San Francisco,

Dr. Goldfoot and Igor pursue them in a cable car that

leaves the tracks to follow them over the Golden Gate Bridge and onto a missile

range where a Navy destroyer fires a round onto the beach that ends the chase.

En route to Paris at Armstrong’s expense for a

vacation, the two bachelors see Diane in the uniform of a stewardess seducing

Gamble’s uncle, West Coast head of SIC. The pilot and co-pilot look on

leeringly, they are Dr. Goldfoot and Igor. At the

last, No. 11 says to the camera, “el próximo

es usted, Señor,” which is the Russian’s warning in

John Osborne’s A Patriot for Me, “you’re next,

mister,” at least in Ronald Eyre’s Chichester staging.

The girls’

standard garb is hat and trenchcoat over a gold

bikini. They are equipped with weapons for rivals and wives.

Dr. Goldfoot’s dungeon holds Dee Dee

in stocks and Eric Von Zipper in chains on his cobwebbed motorcycle. “Why

me,” the latter asks, “why always me?”

Armstrong’s

revolving bar reflects Robin and the 7 Hoods, Gamble meets him there

like Sinatra and Crosby in High Society. The language is entirely

surreal from first to last. “What’s a rotten girl like you

doing in a nice place like this,” says Gamble delighted by No.

11’s erroneous offer at a cafeteria table downtown.

The New York

Times critic fired a soggy squib.