Knights on Bikes

The fate of one

not on horseback but astride Keaton’s velocipede (Our Hospitality, co-dir. John G. Blystone, vd. Stoppard without wheels).

Amelia and the Angel

Here the grand theoretical

basis of all art gets its turn in lines of thought rather like Renoir’s La

Carrosse d’or and looking ahead to Malle’s Zazie dans le métro.

A little girl

plays an angel in the choir that night, after school she takes her wings home

pridefully and her beastly brother wears them to the playground where they’re

smashed. She prays to her saint and guardian angel, goes to her shop, examines

the stalls of a London street. A leetle pair of “beetle wings” from a barrow

won’t do, neither will the décor on Rock the Wonder Dog (Mike Sniver, trainer),

nor yet the stone wings bestowing laurels in the park.

A pre-Raphaelite

artist’s model with lute is similarly accoutered, but the artist himself in

saint’s robe and sandals has to ascend the cherub-ornamented ladder out of

frame and back again to equip Amelia with the very article she requires (artist

and model are pictured on the wall of her room earlier, when she prays).

All of this is

filmed very brilliantly right outside one’s door in London, Amelia herself is

repeated for Women in Love as the girl with the rabbit, the camera

technique includes a POV down the slide and on a swing and scampering along a

deserted train platform into Sniver’s loving arms, the editing is very brisk

and adroit, very expressive, post-synch music and narration crown it, a silent

film of genius with a bit of Alice and Browning’s feather as well as Ernst’s La

Femme 100 têtes (à la Bergman later on in Fanny and Alexander).

Peepshow

Newly-graduated

“bogus beggars” (Die Dreigroschenoper, dir. G.W. Pabst) lose their custom to an

old-man-and-dancing-doll act. They attack en masse but one has a change

of heart and gets bashed on the head with a banjo by a confrere, the rest try

to drown the showman in vain, his magic flute (a soprano sax) pipes them away

on dancing feet.

A film comparable

to Welles’ Hearts of Age, and also to Russell’s much later video work (The

Fall of the Louse of Usher). A silent film with titles written in chalk on

the set producing a most unusual result (cf.

Charles Crichton’s Hue and Cry).

Variations on a Mechanical

Theme

From Victoria’s

loyal bustle (cf. McGrath’s The Bliss of Mrs. Blossom) to Muss on

English organ-grinding (cf. Huston’s The List of Adrian Messenger) and beyond

the beyond (cp. A Kitten for Hitler),

an exercise for Monitor. Schlesinger

without any doubt whatsoever remembers it most particularly in Far from the Madding Crowd.

Michael Brooke

(British Film Institute), “delightful... kitsch it may be...”

The Miners’ Picnic

Dramatically,

John Ford represents Wales in How Green Was My Valley. Russell simply

covers the ground in a composed documentary at Bedlington (Northumberland). The

brass bands compete for musicianship and smartness of uniform, prizes are

given, beauty queens each earn her salute en masse. Dull and daft labor

speeches are endured and rained upon, the miners adjourn to the evening

merry-go-round.

The opening shot

of Truffaut’s Les Mistons, which figures at the very start of French

Dressing, occurs here almost verbatim.

A House in Bayswater

It might easily

have been made twenty years earlier by the GPO Film Unit to document the Blitz,

rather than in 1960 for the BBC.

For there is the

house and its tenants from bottom to top, sleeping in their beds, describing

their lives, seen at work, artists some of them, there is a story about a

wedding party that is quite remarkable, Russell takes a prismatic sort of

dreamlike stretto and then it’s all rubble, picked over by a workman.

Shelagh Delaney’s Salford

Russell was there

before Tony Richardson.

He takes stock, a

very healthy slice of English roast beef, Delaney points out the destruction,

great churches for sale and the like.

The Light Fantastic

A rather

particular London enthusiast demonstrates and joins a guided tour of dancing in

the United Kingdom, which Russell patiently records and then puts to music (cf.

Mahler, The Planets, etc.).

Lotte Lenya Sings Kurt

Weill

“Mack the Knife”,

“Surabaya Johnny”, “The Alabama Song” and “Pirate Jenny”, expertly presented in

four separate vignettes, the first with German film footage directly pointing

out Hitler as Mackie, interspersed with astute commentary from Huw Wheldon.

London Moods

The great city, eating

and slimming, the spiritual city, in a technique comparable to The Planets.

Antonio Gaudí

Gaudí, supremely intelligent as a Stoppard hero, borrows all his

inspiration from the works of Russell.

Teshigahara follows in these footsteps with

color stock and more reels of it, to the same effect.

Pop Goes the Easel

British artists on the tide of popular

culture, surf or swim, they do both with equal facility.

Pauline Boty’s dream of running along a

curving corridor turns up in Wise’s The Andromeda Strain (and Kubrick’s Dr.

Strangelove).

Russell’s Tommy has a partial source

in Peter Blake, Peter Phillips, and Derek Boshier.

The title dates from Del Lord’s epochal

Three Stooges short.

Preservation Man

Astride

a penny-farthing, merry as a lark, to Beethoven’s Bach (cf. the start of French Dressing, also Knights on Bikes). Cult of vanity, cult

of photography, he abstains (Tennyson taught Pound to recite on a cylinder with

“The Charge of the Light Brigade”), amongst Vigo’s dummies. The washed-up

shores of bric-a-brac, speaking integers.

“What

he particularly relishes are those forlorn objects which are too old-fashioned

for use and not yet ancient enough for museums.” The love affair of a Red

Indian and a dinner table set for two, It’s

a Wonderful Life (dir. Frank Capra), “the big Charleston contest!” A babe

in fancy dress, “I invariably wore it to parties, even if they weren’t fancy

dress parties,” cf. Blake Edwards’ Skin Deep. “The Lewisham Hippodrome

every Saturday night.” The dancing dummy that falls apart onstage. How to tune

up a bicycle. “Impression of Sir Henry Irving... blowing bubbles...”

Family

man in “Sleepy Valley”, cp. Dance of the

Seven Veils, Noël Coward’s This Happy

Breed (dir. David Lean).

Elgar

Portrait of a Composer

Very much the situation of the artist defined by his terrain.

Pony, bicycle and motorcar bear him along the Malvern Hills, London is a

disappointment, Germany a salutation. Details are inscribed by Huw Wheldon’s

commentary on Russell’s images, there is the kite Elgar took up flying (it

reappears in Stevenson’s Mary Poppins), his tinkering with inventions

and microscopy in fallowness and mourning. The “deadbeat escarpment” of silent

news footage at 24fps demeans the “vulgar court” and tiresome age and horrid

war.

And within the bounds of non-dramatic representation (latterly

in vogue again on Beeb and Peeb), oscillating between Russell and Wheldon,

cogent images overlap and combine to form a sort of picture obliquely

representing the work and its maker with all the skill of Boleslawski’s film

actor, who must know the part he plays so thoroughly that at any moment any

fragment of it can stand before the camera in complete presence of mind, whole

and entire.

The simplicity of means is emphasized in some stills under the

end credits showing a camera crew of two or three filming the scenes with not a

large apparatus on its tripod, just the surprising way Peter Yates shot the

famous chase in Bullitt.

French Dressing

The gormless

response left it in a warehouse for screenings one day at the Gormleigh on Sea

Film Festival, “to combine Art with Business.”

The first shot of

the title sequence (two shots, tracking shot and pan) is perfect, the second a

stunning articulation of genius, and the punchline is Knights on Bikes (cf. the

opening of Preservation Man for

television). And then, with Nannette Bettina at the h’organ re-mindin’ yew of The Entertainer (dir. Tony Richardson,

with the departure of the Medway Queen

a bit of a taste of honey), h’it’s

pure Fellini, i’n’ it (La dolce vita)?

“I can see through your clothes,” three months after Man’s Favorite Sport? (dir. Howard Hawks—Henry Koster went to the mountain

next year in Dear Brigitte). Bruce

Lacey’s “Artist and Model”. Alita Naughton as the “press agent” behind her

sunglasses and sailor togs resembles Joanne Woodward in A New Kind of Love (dir. Melville Shavelson) the year before (Elio

Petri in L’Assassino put just such

cards as these down on the table for the mayor’s inspection). The inflatable

bikinied F.F. dolls of the French publicity stunt are remembered in the Marilyn

cult of Tommy, George Marshall picks

up the starlet’s rebellion in Boy, Did I

Get a Wrong Number! two years later (the sublimity of Russell’s account is

in her rage, fixed between Anger’s Kustom

Kar Kommandos and Rafelson’s Five

Easy Pieces). The wheelchair parade comes in handy for one of The Boy Friend’s musical numbers,

whereas the historical procession is from Asquith’s The Demi-Paradise. “I swallowed half your stupid sea!” Richard

Lester borrows a gag for Help! the

following year. “Right, gentlemen, shoes and socks off.” Lindsay Anderson

has it in mind in the making of If....,

from the girl’s face to the Zéro de

Conduite town council.

Jean Macabiés of Ciné

Monde has the facts, “qui d’autre que

Vadim aurait pu avoir l’idée de ce film : raconter l’histoire d’une petite

station balnéaire inconnue qui devient célèbre du jour au lendemain, parce

qu’une grande vedette à scandales a décidé de s’y fixer ? Voilà qui

rappelle furieusement la légende de Brigitte Bardot et de Saint-Tropez... étant

bien entendu que toute ressemblance avec des personnages ou des situations

existant ne serait pas fortuite ! Mais le diable Vadim estimant que ce

sujet sentait peut-être un peu trop le soufre, préféra « refiler »

son idée à Ken Russell, un jeune metteur en scène qui brûlait de faire des

débuts fracassants.” Gormeleigh-sur-Mer,

the place is called, Rues de Boulogne

the festival showpiece, a fine feature faked by Alf Russell hilariously but

broken up by a claque, “get all this filthy rubbish off of ‘ere!” The vedette’s Grand Hotel bedchamber is at

the very least from Hitchcock’s The

Paradine Case (and cf. Gordon

Parry’s A Touch of the Sun for the

whole megillah anyway, to be going on with). The vedette departs... leaving the nudist beach unopened. Minnelli’s Gigi springs to mind (and this is all a

way to reach B.B. en verité, and the

character she plays in Et Dieu... créa la

femme). “You’ll never work again, any of you!”

The

cinematography, which is of the finest, will be seen to take note of Losey’s

achievement in These Are the Damned,

among many other things (nothing quite like it, take it all around). The

bravura score by Georges Delerue brings to mind the opening shot of Truffaut’s Les Mistons, but cp. Barnacle Bill (dir. Charles Frend) and

to be sure The Punch and Judy Man

(dir. Jeremy Summers), and Delerue is the composer of Jules et Jim as well as most assuredly Women in Love. Russell later described French Dressing as containing “all the films I had seen in the last

five years,” among which he named “Fellini, Jacques Tati, Mack Sennett and Jean

Vigo,” all certainly visible.

Variety

contrived somehow to find “sheer lack of bright wit and irony.” Radio Times,

“highly original view”. Film4,

“quirky little slapstick number”. Paul Brenner (All Movie Guide), “a slight comedy”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “cinema’s enfant terrible directs this his first theatrical film at breakneck

speed with echoes of Tati, Keaton and the Keystone Kops. Alas, lack of star

comedians [James Booth and Roy Kinnear, to say nothing at all of Marisa Mell

and positively downright snub Bryan Pringle] and firm control [!] make its

exuberance merely irritating.”

The Debussy Film

Impressions of the

French Composer

Arrival of a film crew, “il paraît que c’était un

musicien.”

Pierre Louÿs.

Eastbourne and so forth.

“Jardins sous la

pluie”. La Damoiselle élue. A yawning actress, etc. Baudelaire, Turner,

Whistler. “Fêtes”, processional.

Swimming pool at night (cf.

Antonioni’s La Notte, and Reisz’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman

throughout). Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune.

“Who’s playing Louÿs?”

“I am. Me.”

A Soho cafe, “Gigues”.

“He took ten

years, ten years, over Maeterlinck’s

play Pelléas et Mélisande, turning it

into an opera, and you didn’t understand any

of it.”

A London party, Danses

sacrée et profane, the latter.

La Mer. Children’s

Corner. Berceuse héroïque, commissioned by the Daily

Telegraph (1914). La Chute de la

maison Usher. Syrinx.

Michael Brooke

(British Film Institute), “still represents a career high point.” Ken Hanke (Mountain Xpress), “holding the artist

accountable for the shortcomings of his life.”

Abundantly

illustrating the point made by Boulez, “there

is no doubt that Debussy would have wished it to be understood that he had to

dream his revolution no less than build it.”

Henri Rousseau

Sunday Painter

The work is

abundantly seen in progress (cp.

Savage Messiah), a prodigious feat.

Certain facts,

certain evidence, and a number of anecdotes from the painter’s life.

Always on

Sunday, it’s sometimes called.

Jarry,

“Apollinary”, Picasso. The surrealist mystery of Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street.

Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World

In a sense, another

realization of Buñuel’s idea for a film illustrating the stories of a daily

newspaper (after, let us suppose, Bloomsday), one story in a newsreel like Citizen

Kane.

The real story,

the true one, crystallized as dizziness before the first feature à la

the Press, unfolded throughout “like the tissue / of a Japanese paper napkin,”

the banner waving, the battleship blazing.

“Gloriously

vulgar,” says the BFI (Michael Brooke).

The participation

of a notable biographer tips Russell’s mitt in the way of erudition.

Billion Dollar Brain

Among the major

influences visible (Lean, Eisenstein, James Bond), the most important is

probably Hitchcock, in that Hitchcock receives a complete and thoroughgoing

analysis on a trend of continuous motion, with surprising results,

reintroducing the pleasure of a film that seems to require a Moviola at least

to be sufficiently described, as the early films of Hitchcock do. Psycho

is openly cited with great mastery in Kaarna’s house.

Gen. Allenby’s

oddly Blakean frescoes in Lawrence of Arabia are seized upon and treated

authoritatively. Doctor Zhivago is effectively spoken here. You begin to

see the problem for British cinema posed by Russell, Britmovie calls

this “Pop Art”, and probably means to disparage it thereby, but it’s the same

problem posed by Hitchcock. Much of the flawless editing is done in a handheld

camera used with unerring precision, moreover, and great swiftness. An

admirable analysis is laid on in Hy Averback’s Suppose They Gave a War and Nobody Came.

The costly and

difficult finale is a re-creation of Alexander Nevsky that is

furthermore subsumed in a formal parlance openly prepared by virtuosic

treatment of the earlier foray against enemy forces in Latvia. Palmer wakes to

find himself amid dead bodies in a washroom, menacing types accost him only to

bring him smartly to Col. Stok accompanied by music he is revealed to have just

listened to in a concert hall, after which he explains to Palmer what

Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony means, the Nazis had surrounded Stalingrad,

“they knew they were going to die,” his face streams with tears as he applauds.

The famous music is heard in the subsequent battle, whose outcome is a foregone

conclusion.

Col. Stok’s first

appearance makes reference to Funeral in Berlin (dir. Guy Hamilton), and shows as clearly as anything the nexus

between Hitchcock and Russell. A hotel waiter trundles a cart into Palmer’s

room, takes a glass and listens to the wall, all of this a surprise to Palmer,

it’s the middle of the night, he didn’t order anything, it’s Col. Stok

incognito to return a favor and warn Palmer against betrayal by his Latvian

comrades, “not my men.” Col. Stok undoes the stiff collar of his borrowed

costume with great relief and, talking continually of Lenin and “momentary

interests,” strips to his long underwear, rolls back the tray cover to reveal

his neatly folded military uniform, puts it on, takes a drink and cheerily

departs through the window.

Russell’s

location shooting in Finland is mighty (Griffith) and mighty fine (Kokoschka).

He opens on a streetfront at night in London, the upper windows have a reversed

red neon letter N reflected in them. Someone is searching the live-in offices

of the H.P. Detective Agency with a flashlight (record album of Berlioz on the

floor, Bogart, a Playboy centerfold, dirty dishes, Kellogg’s Corn

Flakes), it’s Col. Ross, brought to bay by Palmer with a pistol, he wants H.P.

back in MI5. Palmer refuses, and instead takes a telephone call whilst opening

his mail, it’s a computer voice with elementary voice recognition for yes or no

responses. Has he received the packet? Will he accept the assignment? Which is

to carry a Thermos bottle to Finland.

A false start

lands him inadvertently where Col. Ross wants him, but only after he “has to go

a very long distance out of his way to come back a short distance correctly.”

His dead contact is Kaarna, MI5. The Thermos contains viruses shortly to be

used in a private military operation against the Soviet Union financed and led

by a Texas oil billionaire named General Midwinter. Palmer quickly sizes him up

as mad, but Midwinter’s billion-dollar computer has the whole plan laid out,

neutralize the Soviet army, foment rebellions and resistance, drive across the ice

in tanker trucks full of troops. Col. Stok sends a few bombers to break the

ice, picks up the plastic symbol representing Midwinter’s forces on his war

room map, holds it in his hand a moment and tosses it over his shoulder with a

smile.

Palmer’s old partner,

Leo Newbigen, now works for Midwinter and is responsible for programming the

resistance activity, but secretly pockets the payroll and agrees to share it

with Palmer, who spills everything to Gen. Midwinter in an effort to avert

disaster. Married father Leo has a new mistress secretly working for Col. Stok,

who gives back to Palmer the viruses filched from a British laboratory and

propagated by a former Latvian Nazi (who takes cyanide rather than surrender).

They had been secreted in egg-shaped containers, and when Col. Ross opens the

package triumphantly (with Lord Nelson atop his column looking on), he finds

live baby chickens.

The performances

are sharp, commanding and subtle. The producers are Harry Saltzman and Andre De

Toth, the opening titles are by Maurice Binder, and the great score is by

Richard Rodney Bennett (who cites Stravinsky’s Les Noces at one point).

The impression

created might be construed as a memory of McCarthy. Palmer knows his enemy, and

photographic evidence of this enrages General Midwinter, who breathes only the

pure air of Texas. The General’s last wish is to “crucify every Red atheist” he

can lay his hands on.

Harry Palmer as

Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe takes his lumps, has his girl, gets the lowdown and

delivers the goods. This is entirely to the benefit of Don Siegel in Telefon,

also Mark Robson in Avalanche Express. Françoise Dorléac’s exit by

helicopter is expanded, analyzed and developed by Robert Altman in MASH.

Dr. No, From Russia with Love, Goldfinger, etc. are more

or less prominently indicated. The trio of code names, Concerto (Palmer),

Piccolo (Newbigen), Sonata (the Latvian germ expert), resembles Len Deighton’s

later Game, Set, Match. The initial reconnaissance foray ends with oranges

strewn across the icy road in a fine image. General Midwinter introduces Palmer

to “my brain” as a product of the 21st century, and tells his “Crusade for

Freedom” troops before the battle, “you are already heroes.” Palmer’s

bullet-shattered windshield fills the screen, he punches his fist through it to

see the road.

Dante’s Inferno

The private life of

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Poet and Painter

Bloody Bolshy

‘ooligans and Luddites, the P.R.B., some fella says, some airy bint with a

Master of Inane Farts.

Your “not Italian—but not really English”

artist, your own, your very own.

William Morris

going ape is in Altered States, later

Borges on Shaw, “a flavor of the sagas.” Gab’s fall recurs very pointedly in The Mystery of Dr. Martinu. “And now

that I have climbed and won this height...”

A pinnacle of

photography, somber construction, and of course the acting and costumes and

everything else is very fine as well.

The Goat of the

Holy Land, the ringing solitudes, patronage, push, the source or wellspring of

art.

Song of Summer

The working title

shapes up to be A Poem of Life and Love. A sublime joke from The

Third Man is arranged for Jelka at the gramophone.

Beethoven’s

surdity, Pope’s valetudinarianism, even Wagner’s hypersensitivity, are

represented in the blind and paralyzed old man who listens to Jerome Kern amid

his own works.

Rev. Thomas Ward

of Jacksonville “taught me everything I know about harmony and counterpoint”.

Delius is briefly

glimpsed à la Charles Foster Kane (passim through the eyes of

Fenby). Forman borrowed the dictation scenes for Amadeus (as Russell for The Music Lovers).

Women in Love

Das

Ewig-weibliche zieht Rupert hinan, Gerald has no such

luck, Gudrun becomes Hermione, tutored by an artist of industry. So the

æsthetic position comes round to its fullest expression and an exit. The

structural apparatus is a consideration of Metropolis

(dir. Fritz Lang) for a cinematic arrangement, as Kubrick had availed himself

brilliantly of Scarlet Street in

making Lolita.

The lens of

youth, an instar past The Rainbow. Everything is seen by this means

alone, even if refracted by childhood or age or reflected back, and so there’s

a constant formula worked out to account for the world in an extension of

childhood that dwindles down to nothing but a whim or wish. An economy of art, Pedagogical

Sketchbooks. A parallelism with Godard, Masculin-Féminin, economy of

love (the French title, an English word).

Truffaut filmed

the “original” of Jules et Jim two

years later, Deux Anglaises et le

continent. The colliery band of The Miners’ Picnic, the father’s

deathbed in Altered States, Isadora, Plath and the cattle, the Japanese

wrestler and so forth.

Vincent Canby of the

New York Times, “if you think of D.H

Lawrence’s novel, Women in Love, as a

kind of metaphysical iceberg...” Variety,

“directed with style and punch by Ken Russell this is a challenging and holding

pic.” Keith Dewhurst (Guardian),

“more like John O’Hara than D.H. Lawrence, more like a respectable best seller

than a probing genius.” Geoff Andrew (Time

Out), “despite a growing portentousness towards the end...” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “surprisingly sane and

classy for him.” Ali Catterall (Film4),

“faithful and frank”. Tom Hutchinson (Radio

Times), “this is one of Ken Russell’s most successful and, for its time, sensational

forays into literature, and it works so well because it is cohesively

respectful of its source (DH Lawrence) and the director, for once, restrained

the excesses that would come to mar some of his later films.” TV Guide,

“tends toward the static, particularly in the later stages.” Britmovie, “strong acting barely

compensates for impersonal direction.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office,

“directed by Ken Russell, the acting is

first-rate, the photography almost too beautiful and the treatment of the

convoluted relationships remains on the superficial level of the physical.”

Lucia Bozzola (All Movie Guide),

“actually does justice to the novel.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “satisfactory rendering... rather irritating characters,”

citing Rex Reed, “call it Women in Heat,”

and Michael Billington (Illustrated

London News), “one-third ambitious failure.”

Dance of the Seven Veils

A comic strip in 7

episodes on the life of Richard Strauss 1864-1949

Omnibus

Strauss is

himself throughout, a most remarkable fact, second only to that must be

reckoned Hitler’s triumph over him as so many.

The artist

stripped bare is an artist, nothing more, an instrument in the ancient sense, a

block of stone carved (Orphée, dir.

Jean Cocteau), “everything and nothing” (Borges on Shakespeare).

“Let me kiss the

hand that wrote Ulysses,” said a fan.

James Joyce replied, “oh no, it did a lot of other things as well.”

Also remarkable

is the legal injunction sought and obtained by the composer’s heirs against

Russell’s film, which vindicates Strauss and is central to Russell’s œuvre (all of his films can be found in

it, or nearly all), as well as in every sense one of the greatest films ever

made by anyone.

The one work of

Richard Strauss not cited yet essential for the form is Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, naturally.

In A British

Picture, Russell gives it a name exultantly, “satire.”

Ken Russell’s Film

on

Tchaikovsky

and

The Music Lovers

“To our great

composer,” says his mother-in law, “Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky!”

The 1812

Overture is perhaps taken from Russell’s own experience as well as

Fernandez’ Enamorada (and Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life). In

despair about the movies after French Dressing, harried from windy

pillar to pissing post (so one imagines) by the inconceivable reaction to Billion

Dollar Brain topping that alas quite off, even (the stuff of legend, it may

be), he is suddenly carried aloft in defence of the realm by Women in Love,

somebody puts a baton in his hand, his enemies expire in a cannonade (all but

the one at one go), bells pealing, getting into the swing of things.

The facts are

given by the London Symphony Orchestra, numerous details of the composer’s life

make up the integument on a fabric of Russell’s combined technique absorbing

the camera into the drama and vice versa. The key of the entire

structure is Richard Chamberlain’s performance, he sets himself within the

great character he represents and will not budge for anything, consequently the

vicissitudes and happenstances are a witness borne by him, the personality of

Tchaikovsky is identified as a response to stimuli. “There are some things,”

says his patroness, “that even a man of his genius must find out for himself,”

the nexus of which she is a part, mainly.

The villainous

reviews begin with an appreciation of Rubinstein’s position and end in a

reversal of the cannonade toward the director, who shows how it was done in the

discontinuous editing of The Planets, whereas here the first five

minutes aim toward an ideal flow of image and music.

But that is the way

throughout the film (and here we have Canby as seasick in the slow movement of

the First Piano Concerto as the composer on the train), comprising as it does

the most musical of cinematic expression with the most moving of dramas, an

ineradicable existence amid blind perceptions (Russell has told the story of

his inertia after the war, from which he was rescued by the concerto).

It is possible to

see a remembrance, if nothing more, of Huston’s The Night of the Iguana.

Mallarmé’s “shallow rivulet”, Polanski’s Repulsion, and René Char’s

“ignominy had the aspect of a glass of water” also figure. Lean’s Doctor Zhivago is a compositional

mainstay.

Vincent Canby of

the New York Times, “boiled to

death.” Variety, “a musical Grand

Guignol.” Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times),

“libelous not only to the composer but to his music.” Nicolas Rapold (Village Voice), “fever dream”. Dave Kehr

(Chicago Reader), “wet dream.” Time Out, “it’s not subtle.” Film4, “much of the film may well be in

questionable taste.” TV Guide, “filled

with wretched excesses”. Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “directed by Ken Russell with characteristic

visual extravagance and narrative weaknesses, the movie’s Freudian approach is

questionable but its interplay with realism and surrealism, objectivity and

subjectivity, succeeds to a surprising degree.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “absurd”, citing Konstantin Bazarov, “a

crude melodrama about sex.”

The Devils

His Great Camp

Majesty Louis XIII (not since the drag ball in John Osborne’s A Patriot for Me) and Cardinal

Richelieu, who envisages a town named for His Eminence... DeMille’s The Ten Commandments for the “Protestant

pigs” manhauling...

Such décor as Things to Come might muster (dir.

William Cameron Menzies). The dead of plague piled wide and deep, a modern

sight. “Every time there’s a so-called nationalist revival, it means one thing, somebody is trying to seize control of the entire country.”

Scenic grandeur

on the scale of Billion Dollar Brain,

the thematic parallel of Women in Love,

the structure of Ophuls’ Liebelei,

homage to Artaud at the stake.

The fall of

Grandier is absolutely swift and dire and takes all of a mauvais quart d’heure to begin, an hour for the naming of him, the

length of the film for his destruction. The girl is pregnant, she has a father,

jakes scryers prevail upon a dying woman with nostrums and delectation,

Grandier soundly rebukes them, chastened they appeal to his enemy, the

Cardinal’s man arrives, “give me three lines of a man’s handwriting and I will

hang him,” but a priest does not marry the boss’s daughter, cf. Hitchcock’s I Confess, Osborne’s Luther

(dir. Guy Green).

Dreyer commits an

everyday witch-burning to memory in Day of Wrath, Russell takes an

extraordinary but in many ways typical case for his panoply of the age. The

devilry is a put-up job to secure a desired result.

The King is Queen

for a day, Richelieu seeks to advance Catholic dominion in the State, Huguenots

are the pretext for a campaign against the fortified towns where local

government obtains, as at Loudun, peaceful coexistence. Father Urbain Grandier,

a Jesuit, leads the town against the plot to thwart its freedoms, among his

enemies in Loudun is humpbacked and besotted Sister Jeanne of the Angels, an

Ursuline abbess, who is made the instrument of his torture and death, whereon

the city is blasted into submission, its fortifications pulled down.

The chicken gag

from Chaplin’s The Gold Rush,

which to be sure Canby did not recognize, is called upon to represent

the Huguenot plight. A fine echo of Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 as the heretic’s lodgings are sacked (“two gross of

broken statues... a few thousand battered books”), another of Don Giovanni (dirs. Paul Czinner and

subsequently Joseph Losey) in court as sentence is read by a hooded Inquisitor

like sounded trombones, her father is a magistrate. The Faust theme is present (not damned into Hell but burned at the

stake), Grandier in the flames is a sight recalled in Altered States.

The last shot is from Kubrick’s Spartacus

(he repays the homage in Eyes Wide Shut).

Cf. Peter Brook’s Lord of the Flies.

“If the Devil’s

evidence is to be accepted, the virtuous people are in the greatest of danger,

for it is against these that Satan rages most violently,” cf. Powell & Pressburger’s The

Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. The title characters do not appear in

their own persons, nor even their signatures on a pact with Satan introduced as

evidence at Grandier’s trial in 1634, a case of what is called judicial murder

rather than the assassination depicted by Eliot (Murder in the Cathedral, dir. George Hoellering) and Anouilh (Becket, dir. Peter Glenville).

“The degradation

of religious principles,” Russell told the Guardian’s

man, “a sinner who becomes a saint.” Screenplay by the director from Huxley and

Whiting, Technicolor and Panavision cinematography David Watkin, witty

choreography by Terry Gilbert on Terpsichore

from the Early Music Consort, capital score by Peter Maxwell Davies from the

Fires of London.

The deplorably

censored bits now visible certainly make plain among other things the eventual

decision by Rome to place the superstition under the ban, rather than the

supposed practice of witchcraft. Jeanne’s “souvenir” suggests Baudelaire’s

calcining Beauty answering the Latin verses earlier on, elsewhere he has “un troupeau de démons vicieux,”

|

Dans des terrains

cendreux, calcinés, sans verdure, |

It was thought by

Vincent Canby of the New York Times to be “of so little substance” etc., which was

Bosley Crowther’s way of dealing with Preminger’s scandalous The Moon Is Blue, he of Saint Joan.

Variety,

“Russell

has spared nothing in hyping the historic events by stressing the grisly at the

expense of dramatic unity.” Roger

Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times), “put them

all together and they spell Committed Art.” Alan Jones (Radio Times), “a highly moral tale of absolute faith.” Time Out,

“best

approached as a diabolical comedy.” Film4, “the real pleasure is in watching

a film by a director for whom ‘too far’ is never quite far enough. The devil.” TV Guide, “one of the director’s most

extravagant fantasies.” Halliwell’s Film

Guide, “a pointless pantomime”, citing Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic, “farrago of witless

exhibitionism”, et al.

The Boy Friend

A matinee at the

Theatre Royal, Portsmouth. There’s a garden fete on in the town, “not a cloud

in the sky”, and so the audience is sparse. The star has broken her foot, De

Thrill has taken the stage box (₤1), leaving the chauffeur outside. The

troupers have a chance to go to Hollywood, they vie for his attention. The

assistant stage manager goes on in the lead after fetching sandwiches and beer.

The style is

Russell’s all the way, from Amelia and the Angel to The Fall of the

Louse of Usher, with that Dionysiac number that exhibits the precision

camera technique, hand-held, already in The Music Lovers (this vital

daydream sequence indicates the play as a torment for the ASM, who merely loves

the leading man).

Fantasies largely

derived from the movies fill the heads of the players, and of course De Thrill

has a creative imagination, the beautifully painted stage production is

embellished with these, each taking place in a moment and lasting onscreen for

several minutes, or replacing in the mind’s eye the number onstage.

Her love informs

her stage presence so that the star, seated with her crutches in the audience,

is moved to tears in spite of herself.

De Thrill recognizes

his long-lost son and takes him back to Hollywood, she tosses away the card

she’s been given inviting her to a screen test and goes off with the leading

man.

Bright girls in

the footlights, showmen, razzle-dazzle, a pantomime or harlequinade, from a

thoroughly engrossed vantage (Humberstone’s Happy Go Lovely) to a

British musical invented sometime before the war, with all the advantages of

Sadler’s Wells and Powell & Pressburger and Ealing and the Free Cinema, no

horseplay unintended.

The intricacies

of the play mirror the action and are a little drama unto themselves, as always

in the musical.

Ebert paid the

supreme compliment of disparaging Russell as Busby Berkeley’s equal in

“fundamental visual poverty”.

Russell’s

indefatigable labors, which include a creation of Thirties ambiance so complete

that characters seem to come out of films, and the fundamental recognition of

arrangements as integral to the style (Peter Maxwell Davies has this), wore out

M-G-M to the extent that as much as half an hour was cut, despite the

complexity of the work, one sign of which are the brisk references to

Sternberg’s Morocco and Fellini’s 8½ in that very brisk number

from Hollywood, “It’s Nicer in Nice”.

Savage Messiah

Too much grip,

not enough grasp (“The other way, the other way. I thank you.”) in Jolly Olde

before the Great War, Henri Gaudier Brzeska there between two stools (women,

worlds) with more of either than the market will bear or even comfortably

envisage (cp. Shelagh Delaney’s Salford).

A classic, HGB,

“anywhere in the world, anytime at all, the classics always work.” (JLG)

The great Van

Gogh joke is played as a lark with a chisel to pierce his own ears, hardly

noticeable, even.

“It’s easier to

become prime minister of this country than one of its artists,” says the art

dealer.

The work is

heroically shown in preparation twice, the “neoclassical” Torso and the Bird

Swallowing a Fish, chisel in hand, mallet to it.

Among the

misunderstandings promulgated by leading film critics is the crucial one that

says the artist is not first-rate, the point being that he was killed in action

very young, just the age of Shelley’s Keats or nearly.

Pound took the

trouble to write his epitaph in lines taken to heart by the screenwriter and

the director so that there is no possibility of a misunderstanding...

|

There

died a myriad, And

of the best, among them, For

an old bitch gone in the teeth, For

a botched civilization, Charm,

smiling at the good mouth, Quick

eyes gone under earth’s lid, For

two gross of broken statues, For

a few thousand battered books. |

Mahler

The extinction of

the artist is a Lincoln dream transposed out of Dreyer’s Vampyr, it

presages along the same inarguable lines Kafka’s fate of European Jewry.

That is well and

good, an absolute nightmare from which the artist awakens on the lap of an

abyss, the studied whoring of a copious future all behind him now, the doctor

is waiting at the next station (Freud’s train ride).

The excruciated

labors of this go into the making of Lisztomania as a more easygoing affaire

d’honneur. The budget is a laughable fraction of what anything costs in

movies anywhere at all, and looks for all that as if Korda’s Rembrandt bought

his film stock out of bins of color at the corner shop, weighing it judiciously

in the light.

When the Bard had

once been convicted of plagiarism, The Charge of the Light Brigade had

to be written by someone else, a veteran. “It’s all very well,” said

Richardson, “but we can’t have Queen Victoria fucked by a Russian bear, now can

we?” And so on.

Le monde et le

pantalon. Freud again, the sad

pupil of Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste, the “je ne sais pas”

of Mallarmé’s toast, Lolita’s piano lessons, Griffith’s Broken

Blossoms. And the curious stained glass of inspiration.

Doré in

excelsis on the rostrum. Vampyr, looking ahead to Altered States,

Bye Bye Braverman (dir. Sidney

Lumet). Henry V (dir. Laurence Olivier) at the crematorium

(Hamilton’s Diamonds Are Forever).

The Music

Lovers, over and over again, and

again Altered States for the naked Wolf acknowledging his critics. Isadora

Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World, Lang’s Siegfried.

Hitchcock’s transmuted scream and the rescue of 1904 (“it was hot,” says Alma),

Altered States.

The dullards and

madmen of the press were impressed with pity for the artist, which becomes

them. Russell transmutes Ford (and the theory of comedy) on the interesting and

the beautiful.

Everything is in

it, of course. Nothing is lacking. Mahler sought to raise Vienna from the dead,

Russell accepts the miracle (cf. Aria, “Nessun dorma”),

supplying very rare jokes, the composer is amused as can be at the spectacle of

Visconti’s Death in Venice. Women in Love for “what Nature tells

me”, Chico Marx hits the spot, Harpo, Jolson “....and then came the TALKIES!”

Structure of a symphonic development.

Tommy

A child of the

Blitz (cf. Powell & Pressburger’s

A Matter of Life and Death).

Certainly the ‘uggetts h’on their ‘oneymoon h’and ‘olidays h’is h’evoked from

Ken Annakin, Shelagh Delaney and John Osborne... and Shakespeare, for the

little perisher is ‘amlet by ‘itchcock (Marnie).

|

You didn’t hear it, you didn’t see it, you won’t say nothing to no-one ever in your

life. Now he is deaf, now he is dumb, now he is blind. The guilty are safe but always accused by his

empty eyes. |

The divine

Marilyn with her skirt up, start of a meditation on Metropolis (Fritz Lang, cp. Crimes

of Passion). Cousin Kevin, “the school bully”. Uncle Ernie “fiddling

about”.

Das Glasperlenspiel (Hesse), derived here from the war works (cp. Lisztomania, also Antonioni’s Blowup). Hi Detergent and Rex Beans and

Black Beauty (“A Thoroughbredly Good Chocolate”) pour out upon Une Femme

mariée (Godard, cf. Makavejev’s Sweet Movie). The physician from

Harley-Davidson Street. Lunchtime Luna

(Bertolucci, cf. Brook’s Marat/Sade).

The second birth

is by the means espoused in Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète, also Richter’s Dreams That Money Can

Buy. Earliest use by Russell of process shots for free backgrounds

(cp. A Kitten for Hitler and Lotte Lenya Sings Kurt Weill, here with

a sense of Blake’s Albion), perhaps.

“A rock musician from California” (Lisztomania).

Fellini at Tommy Holiday Camp. Revolt of the glass beads. The climb up the

mountainside is Richard Thorpe’s Fun in Acapulco.

It is certainly

better, as Debussy said, to see a sunrise than to hear the Pastoral Symphony.

Nevertheless, the Pastoral Symphony is also something not to be missed.

Mahler

as paterfamilias here, significantly.

A way out of the

mess evoked by several cults, even the cult of oneself. Remarks upon it are generally

uninformed, yet Variety heaped praise, “a superbly added visual

dimension.”

Vincent Canby of

the New York Times, “an elaborate

put-on... all fairly excessive and far from subtle, but in this case good taste would

have been wildly inappropriate and a fearful drag.” TIME, “weird, crazy, wonderfully excessive”. Geoff Andrew (Time Out), “watching his more excessive

movies tends to be a wearisome experience.” Andrew Sarris (Village Voice), “excitingly grotesque.” Film4, “Russell’s hypertrophied direction...” Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times), “one glorious excess

after another.” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader),

“and the results are somewhere between the apocalypse and Andy Warhol.” TV Guide, “Ken Russell applies his

rococo outpourings”. Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “director Ken Russell’s

treatment is ludicrously out of control, obscuring the sense of the opera by an

undue emphasis on visual pyrotechnics that is not dramatic but destructive.

Satiric jabs at religion are excessive if taken literally.” Perry Seibert (All Movie Guide), “with his penchant for irreverent interpretations...” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “of occasional interest.”

Lisztomania

Baudelaire’s Thyrsus, “et une gloire étonnante jaillit de cette complexité de lignes et de

couleurs, tendres ou éclatantes...” The

opening duel and the substitute cult are from Dance of the Seven Veils.

A very comfortable

presentation of caricatures taken to an irredeemable point of issue, beyond

which there is Abbé Liszt as Matt Helm vs. the Frankenstein rockstar in Tommy,

little Dickie Wagner’s übermensch.

Rienzi and “Chopsticks” make for the mad approbation of

schoolgirls, the creature is wiser than its maker and knows all about pissing

on a fire with Ives, until the final adjustment.

Fellini’s Casanova

(cp. Gothic), surely. The

“Millionairess” and the beggar, the “Most Promising Actress” and the

revolutionary, the “Princess” and the savior of Germany.

The artistic

economy that here lays the basis of Russell’s later style is a structural

identity with The Devils, this allows a tremendous concentration of

force upon the speed of his images and the characteristic jointure of his

thematic constructions. The reason for it is that there is something to express

that can only be said at a certain velocity. Freud is the happiest analysis

offered all throughout.

Eisenstein’s pram

gets a good going-over, Casino Royale (dirs. Huston et al.) is

the significant source of the Dickie farce (cp. Mata Bond in Ost-Berlin), Great Catherine (dir. Gordon Flemyng)

figures pivotally in Saint Petersburg, Dreyer’s Vampyr has Franz at the

stained-glass swastika window before expiring towards the Elysian heights.

Richard Eder of

the New York Times, “a noisy bit of

pretentiousness”. Alex von Tunzelmann (The

Guardian), “Franz Liszt (1811-1886) was a Hungarian composer.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “what does all this mean? Nothing at all.” TV Guide, “bizarre, sexually obsessed biographical fantasy.

Russell’s style works in some parts but often ends up in self-indulgence

disguised as surrealism. The result is a shockfest.” Time Out, “the result is not only catastrophically wide of the mark

as a ‘sense experience’, but misogynistic, addled and grandiosely witless. The

most pitiable aspect is that Russell is here patronising his collaborators as

much as he’s always patronised his audience.” Film4, “another of

Russell’s gloriously indulgent follies.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “most excessive and obscene”, citing Tony Rayns of the Monthly Film Bulletin, “completely

umitigated catastrophe”, Patrick Snyder of Crawdaddy,

“bludgeoned into pulp”, and a reviewer from Sight

and Sound, “like a bad song without end.”

Valentino

The Temptation of St. Rudy (Lasky’s ape) is a missing link from The

Music Lovers to Altered States.

Rambova’s séance comes from or points out the crucial scene from

Buñuel, Jesus in the whorehouse (L’Âge d’or).

Fellini the Italian Russell is concurrent with his Casanova,

equally misprized.

Singin’ in the

Rain is just around the corner

from the Citizen Kane parody in silent Hollywood, as grand as anything

and hopelessly full—replete with genius.

That puts the

kibosh on the great career as smilingly contemplated and assiduously

entertained. “All you need in movies is to look sincere,” the well-paid

erstwhile waitress from Dallas explains about acting. “Let me tell you,

brother, lookin’ sincere in this town is a lotta hard work.”

Clouds of Glory

William and Dorothy

The Love Story of the Poet

Wordsworth and his sister

“Louisa”, the poet’s running commentary, like Gaudier Brzeska at his

studies.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

The mania of Coleridge, by way of Preminger’s The Man with the

Golden Arm.

Altered States

In the minds of

the great public, artists will have to be considered as apes gone feral at the

zoo (cp. the jailhouse scene in Valentino).

For academics, another matter, there is a kind of swirling gray matter, a

return toward the time there was before there was time, a state of despair as

preceding creation, a black hole (this is indeed a mirror of unsatisfied

curiosity). Time mends the first “altered state”, Shakespeare is hardly ever

thought of as a poacher nowadays. The second leads merrily to a rescue of the

imperceptible artist by the creative matrix of biography, represented by his

wife. This continues by a natural process to the third altered state under

consideration, the private man.

The general view

is more or less conditioned by academia, he is more or less a learned man, so

(it may be) is his wife, these are all temporal points defining his curve, the

track of his flight.

His reputation

steeply declines upon his death because he has not the daily fight to wage of

pounding the walls to shake free of a certain conditioning, a received idea

that once shaken off restores him to humanity once more, and to his wife.

That beautiful observation

has nothing to do with the film, which is an analytical understanding of Women in Love. The idiosyncrasy

manifested in Jessup’s psyche by means of his several hallucinations is Gerald

Crich’s, Rupert Birkin’s aspiration is his. The identification in a single

character is seen with Urbain Grandier (The Devils), the situation

occurs (a Blakean marital row of sense and soul) in Mahler.

The medieval

doctors of The Devils are entirely updated. Rimbaud’s famous

pronouncement on the seer is indicated.

Mahler (by way of Dreyer’s Vampyr), The Music

Lovers, Savage Messiah, Tommy for the man in the tank.

Stevenson and

Kafka, beyond which there is Borges, Jack Arnold’s Creature from the Black

Lagoon, The Incredible Shrinking Man and It Came from Outer Space,

also Kershner’s A Fine Madness.

But most simply,

Arnold’s Monster on the Campus.

The Planets

by Gustav Holst

performed by Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra

a personal view by Ken Russell

MARS

The Bringer of War

Hitler hot from

Hell, the fire that sent him back again.

VENUS

The Bringer of Peace

As Riefenstahl’s Olympia to her Triumph.

MERCURY

The Winged Messenger

Flight and

descent (cf. Richter’s Dreams That

Money Can Buy).

JUPITER

The Bringer of Jollity

The sublime of

joy, exaltation.

SATURN

The Bringer of Old Age

“Whilst this

machine is to him...”

URANUS

The Magician

Hoc est

corpus...

NEPTUNE

The Mystic

Grand summation (cf. Beckett’s Quadrat 1 + 2).

A purely

cinematographic study adhering to Holst’s particular program, composed entirely

of heterogeneous images chosen from the library and fitted together in relation

to his masterwork and Russell’s understanding of it in such a way as to

illuminate the composition and the cinema and much else besides.

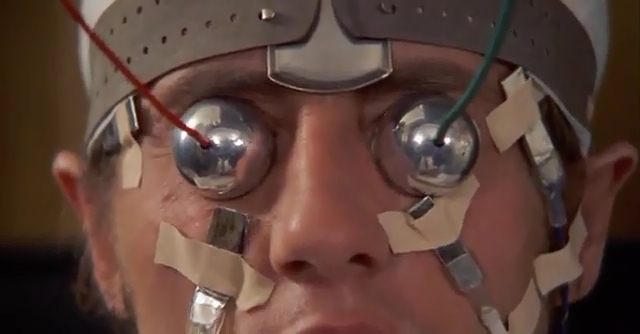

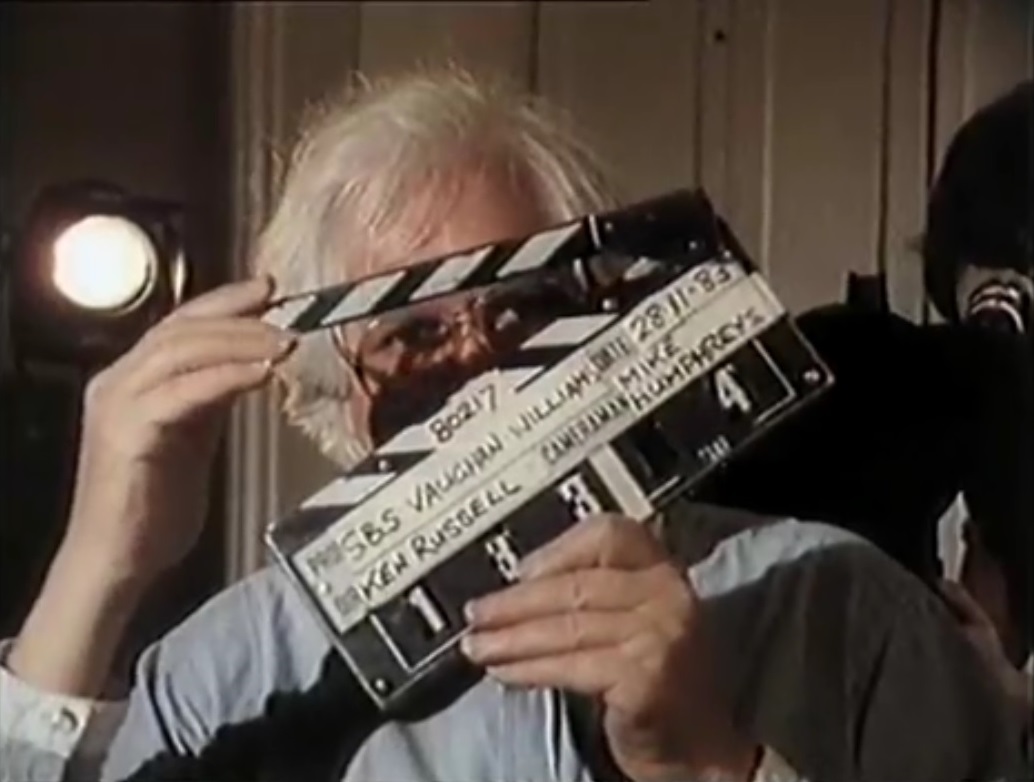

Vaughan Williams

A Symphonic Portrait

That is, from a

picture-book biography for a very young daughter (“ah,” the erstwhile Royal College of Music, “now that’s a funny place, isn’t it”), and

interviews with Ursula Vaughan Williams by the sea, for instance, and Russell’s

great sea studies with the Symphony No. 1, and the director at work on all this

or between shots, and so forth (cp. The

Debussy Film).

Back into the

cave with Kazan (The Last Tycoon),

which is the cathedral, “the cinema was our academy and our cathedral,” says

John Osborne (it mystified the television critic of the New York Times). London for the Second, which takes Russell back

into London Moods and The Light Fantastic, this time in color

like The Planets and looking ahead to

the ABC of British Music (Susan

Penhaligon at the Strand in Stoppard’s The

Real Thing). The ‘14 War, Cocteau calls it, the Pastoral Symphony. The Lark Ascending played in the fields

like Women in Love. The Fourth a

portrait of the man. The Oboe Concerto and an expert. Dona Nobis Pacem at the Tank Museum, a peculiarly Felliniesque

flair. At the resumption of hostilities, the Fifth, another pastoral scene

(recalling Dance of the Seven Veils).

The Sixth with Vernon Handley and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, The Loves of Joanna Godden (dir. Charles

Frend). Penguins and Scott of the

Antarctic, the Seventh (Russell playing dumb in the front row, attentive in

the clips). The batterie of the

Eighth in the foyer of Royal Festival Hall with a view of the Thames. Dover, Four Last Songs. Stonehenge, the Ninth.

Russell’s

sublimest, most seemingly offhand inventions throughout.

Michael Brooke (British

Film Institute), “uncharacteristically restrained... Brechtian...” John J.

O’Connor of the New York Times, “not

about to settle for being commonplace.”

Crimes of Passion

China Blue AKA Miss Liberty 1984 works the boulevard while Rick Wakeman

plays Dvořák’s “New World

Order” Symphony.

The American cut

is to be eschewed at all costs, there Beardsley and ukiyo-e are not allowed in public auditoriums without an X.

By the same

surrealistic process, the screenplay identifies only two characters with a

multitude. China Blue designs clothes by day and lives alone, she is the

unloving wife in the suburbs (“cable’s in but the hot tub ain’t ready,” Lenny

Bruce might say) whose unhappy husband runs a security shop in a Hollywood

strip mall, he is the Reverend Peter Shayne trying to save her with his dildo,

“cruise missile or Pershing?”

Faust

Moonlight, wisps of cloud. Body snatchers bring in a coffin, Faust

brings to bear his Frankenstein apparatus, she rises and dances—and dies,

bidding him farewell.

An opera director

has not the same resources as a film director, he has the image, his objective

correlative, and Russell has the multicamera system Czinner pioneered as well.

Stravinsky’s Tom

won’t act, Gounod’s Faust can’t, he casts away his age in Mephistopheles’ cloak

like Strauss on the podium (Dance of the

Seven Veils). The unusually large cannon suggests Lisztomania, or rather The

Pride and the Passion (dir. Stanley Kramer). Marguerite takes the veil,

Valentine is off to the wars. The Golden Calf that might have inspired

McGrath’s The Magic Christian “in

blood and filth” has eyes that roll like a slot machine, it dispenses gold

coins from its mouth. Wine pours from the bleeding Christ, a broken sword is a

Cross made of chocolate to defend one from Hell... where opera directors go who

do not understand the art per Tony Richardson (The Phantom of the Opera), whereas here... Mephistopheles pees in

the holy water, as Debussy would say, and hangs his hat on the crucifix above

it, thus begins Act III.

Whereas here the

proper elements of opera are seen to glide by in various succession, poetry,

music, pictures, dancing, drama, with extraordinary swiftness, nothing like it

elsewhere. For it is indeed prismatic, even kaleidoscopic, one moment the stage

effect, another the tune, a ballerina next, the singing then for a moment, and finally

the dramatic effect combining all these in a single expression, nothing more

than a sigh perhaps. Bejeweled Marguerite in her nun’s habit, “a king’s

daughter.” The exquisite love scene.

D.W. Griffith

(Acts IV & V), with interpolations from Russell. The guillotine is yet

another Cross, Faust in his laboratory receives another corpse, male,

unassisted it rises to accuse him (“Christ is risen!”), he sinks down into

Hell.

Gothic

The unique

precedent is Alain Resnais’ Providence.

Russell opens with the return of the beloved (Dante’s Inferno) and Shelley’s arrival à la Percy Grainger (Song of

Summer), the enshrouded female figure at the start of Mahler occurs passim.

One of the finest

English films splits open the pomegranate of an onlooker’s mind to reveal the

stark self-realization in the face of genius as a series of nightmares so close

to the poetic imagination as to recall Auden’s censure of his colleagues as

“superstitious” to an extreme degree.

These are the

nightmares of poets, more intense and horrible because they are possessed of

finer imaginations, or perhaps rather these are the nightmares foisted upon

poets by their admirers and detractors, but the impression throughout is of the

poetic imagination at bay and forced to create because of it, Mary Shelley’s

hallucination, Frankenstein.

The humor of it

is aided by tourists before and after, viewing the site (Byron’s abode).

Thomas Dolby’s

score is very apt with quotations and nuances and off-putting asides. Russell’s

technique is to move very fast, cutting almost subliminally at times, to

achieve the inner tempo of his regularly accelerating nightmares. This alone

accounts for the critics missing the boat.

Fuseli has the

nightmare vision corresponding to this, the rare sort of imp that crawls upon a

lady in her bed at night to perch there on her lower parts, staring not at her

but at the spectator, neither faun nor gremlin specifically, a nameless sort of

untoward horror. Unless it be granted that his Nightmare is a variation

of the theme expressed in Poe’s “The Raven”.

This is the

occasion described by the authoress, so like Poe and Borges, of The Modern

Prometheus, “perhaps the component parts of a creature might be

manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.”

The so-called

terrors of art pertain to the mind alone, as Byron points out here.

Every image is a

precise term in a surreal language stating the problems of comprehension that

follow inspiration, “that hurtles from heights unknown”.

Nessun Dorma

Aria

An application of

Dreyer to the specific problem of Lang’s Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse,

already prefigured in the opening credits of Quincy, M.E. (where you

find the dissection gag in Mel Brooks’ Dracula: Dead and Loving It).

The conjunction

with Godard is salutary and fortuitous. “Only Hitchcock and Dreyer have filmed

a miracle,” in part

three (« Le contrôle de l’univers ») of Histoire(s) du

cinéma.

Ken Russell’s ABC of

British Music

The idylls and

the idiocy. Elgar’s house gone to rack and ruin, two weeks from demolition,

“you couldn’t get a ticket to see Elton John for £15!” Welles complained that

Spielberg had bought a Rosebud sled at auction for $50,000 and wouldn’t give

him a dime to film one of his unproduced screenplays (Spielberg called it “a symbolic emblem of

quality in the film business”), Tom

Waits raised $90,000 for the homeless

with a chapbook of poetry.

“F is for film

music,” Vaughan Williams, William Walton, John Ireland, Arthur Bliss (Russell’s

hand can be seen in a précis). Thomas Dolby scoring Gothic (“my latest feature film”) à la diable...

Webber’s Requiem No. 3 in a Choral Top Ten headed

by Belshazzar’s Feast. Sir Michael

Tippett nix. Kate Bush. Iron Maiden.

“The greatest

opera of modern times, Troilus and

Cressida” of Walton.

“P is for punk

and Purcell.”

Scotland, a

bonnie lassie.

Nigel Kennedy,

top soloist. The Critics (cf. Dance of the Seven Veils). Tippett off

message oke. Havergal Brian.

Uncle Eltie in

McCloud’s red red Rolls (“The Moscow Connection”, dir. Bruce Kessler). Wales a

reverse striptease (see Scotland). Xylophone (Evelyn Glennie), Youth, and Zadok

the Priest.

In and out of the

muckheap and mania, a great artist draws the thread.

“A video

encyclopaedia megapack,” Melvyn Bragg calls it (“Edited & Presented by”).

Salome’s Last Dance

The play in

English, with its beautiful crux, and the critical response. Or, a pubescent

Mae West vs. a Pre-Raphaelite Baptist, a cinematic transposition accurately

placed within a sort of macaronic mise en scène that is largely adduced

in loving detail from Pabst’s Die Büchse

der Pandora (Alwa’s revue, featuring die

kleine Lulu).

The critics, the

damned and foolhardy critics, will doubtless prattle of Russell’s “excess”, in

that manner of speaking to which we have long since grown accustomed after a

fashion, or deaf. “So you’re the one they call the excessive doctor,” says

Cajetan in Osborne’s Luther. “You don’t look excessive to me. Do you

feel very excessive?” The doctor replies, “it’s one of those words which can be

used like a harness on a man.” The courteous Cajetan asks him, “how do you

mean?” Dr. Luther (“conscious of being patronized”) explains, “I mean it has

very little meaning beyond traducing him.”

The fate of Salome

is eloquently described by Russell, “it was death by misadventure, she slipped

on a banana skin.”

To her prize on

its silver platter Salome still argues, “the mystery of love is greater than

the mystery of death”. Critics (Hal Hinson, Desson Howe, Roger Ebert, Geoff

Andrew, Film4) gnashed their teeth upon her unpleasant revelation, so be

it, Canby correctly placed the work “among the earlier Russell biographical

extravaganzas”.

A silver box of

cigars upon a silver tray in the pale hands of an ill-favored Cockney skivvy

whom Wilde describes as “undernourished”, and just before the end of the play,

the little bootblack whom Bosey proscribes as “the Golden Calf”.

Herod has no

objection to curing the sick, “a good deed”, it’s Jesus raising the dead he’ll

have nothing of.

Millais-Scott

says her arias in such a way as to equal the beauty of the original.

The tiny stage in

a “disorderly house” (with “clients and courtesans alike” in the parts)

effectively represents the moonlit terrace of Herod’s palace.

Wilde is

strangely moved by his own creation in a whorehouse that caters to one and all,

where the brothelkeeper plays the Tetrarch for him, and the butler is a Roman.

Beardsley’s drawings accompany the opening titles.

Rodin’s Balzac

has a cloak, Kenneth Clark tells us underneath it at the first presentation was

the nude portrait waiting to expose academic critics at the drop of the

sculptor’s hammer. By the same token, Russell’s hermaphroditic trick is already

on Beardsley’s title page.

The Lair of the White Worm

St. George and

the Dragon in the style of Universal-Corman-Hammer.

The worm god

Dionin has its avatar and priestess in Derbyshire (cf. Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, dir. Tony Richardson) maintaining human sacrifice and vampiric

zombiedom, it is a virgin sacrifice of course, hermaphroditic (Salome’s Last

Dance), and makes for some exceedingly fine nightmares. Dionin is wroth

still over a convent set up at the place of his worship (his “holy of holies”,

as the Reverend Peter Shayne would say), the immemorial priestess once caroused

with a rebel Roman emperor, and so the vision is of nuns ravished by a legion

whilst the great worm curls around the crucifix of Christ.

An amusing

streamlined remake in the sunny American Southwest (Tremors, dir. Ron Underwood) followed a

great scholarly analysis as one in a series of Archie’s Weird Mysteries.

The Rainbow

The prism of

childhood, among other things that are outside its knowing purview.

The world as it is,

a learned thing, an acquired taste.

Since that is its

discourse, the film is sedate, relatively speaking, to give the moral gravitas

of scenes perceived by a girl without uncommon wisdom or insight, a foolish

girl.

And her defense

is her childishness, something more and less than innocence.

After all, the

world is an elaborate apparatus, time is one of its elements, there are traps

easily sprung and stepped over, with a brisk smile.

And this is

Ursula Brangwen (Women in Love), whose sister Gudrun pulls men’s hair.

A British Picture

“Portrait of an

Enfant Terrible”, a very brilliant and amusing film for British television, an

autobiography, a self-portrait as the wee lad who did all that, made all those

films and this one.

The Strange Affliction of

Anton Bruckner

A very precise

medical disorder, a mental complaint, he had to number the sands of the sea

like Augustine’s vision, Russell films him at it, the sort of thing Auden might

have written with his contempt for the dreary numeration of Don Juan.

Cold baths in a

clinic, his bedchamber just suggests Van Gogh’s at Arles. A religious man, a

churchman in his pastoral hat, a Catholic at confession.

A keen impediment

to the composition of great works, therefore you have in this kind jesty madman

a picture Beckett might describe as “Bruckner in the throes.”

The hairs of your

head, the stars of heaven, the divine creation (Women in Love).

The initial shot

recurs, “you are not ill” (cf.

Fellini’s 8½).

Script and camera

by the director. Jochum/Berlin, Astarte.

Whore

Prostituted L.A.,

five years or so. The location filming is cagey, always a very precise locale

and not seen properly, as when the camera has its back to the Bradbury

Building, or lumbers around Grand and Olive, a few movie theaters (one showing Fantasia),

or lets you know it’s Century City (formerly Twentieth Century-Fox).

It seems fairly

safe to say that it was not well observed by the critics, because it doesn’t

miss a thing and they all did.

Kenneth Turan (Los Angeles Times), “heroically tedious”

Prisoner of Honor

Dreyfus, also

Picquart (Prisoners of Honor, “this

book”).

The affair begins

with the degradation of Captain Dreyfus, degradingly in “slo-mo”, and ends with

him a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (Picquart is seen as Minister for

War).

There are

entrancing echoes of Kubrick’s Paths of Glory and Hitchcock’s The

Wrong Man, and a near-quote from The Devils on a bit of handwriting

hanging a man.

Lieutenant

Colonel Henry deliberately drops an Edison cylinder of Mahler, “a Viennese

Jew”, upon taking over Colonel Picquart’s office, it breaks.

An affair of honor

does take place, the saber duel between “ignorant oaf” Henry and Picquart.

Dreyfus accepts a

pardon, Picquart reminds him of his duty.

The essence of

the argument is Picquart’s understanding of duty, “I don’t believe that my

personal code of honor and the honor of the Army are in conflict.”

Esterhazy tells

it all to a writer in England decades later.

The Minister for

War (Lindsay Anderson), “no sensible man would allow himself to be sent to war

for a politician. But, there is the flag, he’ll fight for that, and the Army

holds the flag, and I am responsible to tens of millions of French men and

women to ensure that nothing is done to destroy the prestige of the Army. What

would you do, Colonel, what should I do sitting behind this desk, balancing a

possible injustice to one man against the lives of millions? This [the Gatling gun] goes into service next

month, the Germans have it too, it fires 600 rounds a minute. It won’t wound

you, it will saw you in half. From now on, survival on the battlefield will be

a matter of statistics, not of individual merit or bravery. The only thing that

will keep a man in the firing line will be discipline, and the belief that the

high command knows best, that it will never, that it can never, make a mistake.

Are you prepared to destroy that belief, Colonel?”

The cabaret act

parodying the Marseillaise (“destroy these filthy Yids, restore our honor and

our gold”) echoes Losey’s Mr. Klein.

Picquart holds no

brief for Jews, but as a cavalry officer reluctantly placed in charge of Counterintelligence

and specifically asked to look into the Dreyfus affair he finds himself almost

at once in possession of the facts. The question that begins the film is one of

motive, “why did he do it,” asks General Boisdeffre, referring to Dreyfus now dead

(“as good as”) on Devil’s Island, the Minister for War speaks of his “widow”,

the General changes his tune, “Dreyfus stays where he is. That is how he can

serve his country best. There is more to this than the career of one artillery

officer.”

Picquart’s love

affair recalls Richardson’s Captain Nolan in The Charge of the Light Brigade. To the tune of “Frère Jacques”

provincial children sing,

|

Alfred

Dreyfus, Alfred Dreyfus, Dirty Jew! Dirty Jew! Safe on

Devil’s Island, safe on Devil’s Island Let him stew, let him stew. |

The inspection

tour of outlying installations is a feature of Terence Young’s Mayerling, for example. “Whatever you

think of him,” the General sticks to his guns after a fashion, “whatever has

got into his head, Colonel Picquart is the sort of officer that the French Army

cannot do without. I will not have him put at risk skirmishing with native

tribesmen. This has gone far enough. Bring him back.”

Jews are attacked

in the streets of Paris, an effigy is burned, “the Jews killed Christ! Dreyfus

killed France!” Picquart is nonetheless “a serving officer,” as he tells Madame

Dreyfus.

“Esterhazy is a

traitor! That’s what I have against

him. Petty of me, I know.” Thus Picquart in his cups. A long, winnowing view is

obtained before Dieterle is brought into play, therefore (the General describes

Henry and his ilk as “nosepickings”), or to put it another way, the central

figure is neither Zola nor Ferrer’s Dreyfus but Picquart, who facing a drunken

threat replies drunkenly, “I will not go to my grave knowing that the Army has

protected a traitor and disgraced an innocent man.”

General Mercier,

who tells the story of the drunken commanding officer, refuses Boisdeffre’s

resignation, “I will not have the Army of the Republic destroyed by Dreyfus.

The traitor and pornographer Zola was right about one thing, there is a conspiracy here, between the Jews

and Socialists. We are fighting now for the life of the State itself. We shall

fight on.” The later cabaret recalls, among other things, the opening shot of The Devils.

Esterhazy, “the first twentieth-century man.” John

Osborne’s play A Patriot for Me

(filmed by István Szabó as Oberst Redl)

has a small role in the production, one might say.

Robert Pardi (TV Guide), “apparently tickled pink to

be playing historical personages in a prestigious cable-TV production, the cast

declaim like highschoolers at a regional Shakespeare competition... it’s hard

to believe that notorious bad-boy director Ken Russell played any part in this

handsome-looking pageant, and Ron Hutchinson’s speechifying script deadens

material that was better handled in The

Life of Emile Zola (1937).”

Road to Mandalay

At home in his

home town, the director en famille

strives vainly in his Renault to reach the goal of luncheon curry (“I would

like an Indian pizza,” says Russell fils),

one is straight out of Southampton and on the Isle of Wight before one can say

Defoe’s Robinson, “just like the Blitz,” Aunt Muriel observes upon the return (cf. Lumet’s Bye Bye Braverman).

The Phantom of the Opera

As fantastically,

ideally, awfully dull as Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber, Russell’s three videos.

The Secret Life of Arnold

Bax

Like Handel at

the Victoria & Albert, one shoe off and one shoe on.

“The poet and the

secret wish.” (Nemerov)

Cp. Dance of the Seven Veils for the director

conducting Mr. & Mrs. Strauss, the second Elgar film for the seaside muse,

and of course there is Peepshow.

Tom Service (The Guardian), “eccentric musical

obsessions... eccentric auteurs... outside the mainstream... fantastical

dreamers.”

Lady Chatterley

A masterpiece of

British Art.

The theme skirts Rebecca and Under Capricorn most skillfully, which is exactly what it was

intended to do.

Lubitsch could

not have handled it better.

One would like to

praise Jean Claude Petit for a peculiarly amiable score and its lovely tune,

which comes over the wireless in an important scene early on as a respite and

relief from war memories.

Russell is the

operating cameraman. The location (manor house interiors) is the same used in Gothic.

The technique is refined out of The Rainbow as a kind of plainspokenness

that must defeat the strangest critic, even the one from Entertainment

Weekly (“a total snore”).

The little tune

expresses the tragic circumstance and is simply an English tune of old, as it

sounds.

The gamekeeper

and the lady, the invalid and the district nurse, quite a lark in its way, with

some terrible things. An erudite treatment of the material, as reported, in

Lawrence’s workshop, whence the curious reflection that only seems ready to

hand but is nearly if not entirely obscure, commended by the Bard as useful in

the range of art, if only to convince the onlooker that idle fancies are not

the scope of the production.

The calm naturalism

is perfect English poetry, the marriage of Sir John Thomas and Lady Jane, after

all. “O my America! my new-found-land.”

The Mystery of Dr.

Martinu

A Revelation by Ken

Russell

An oneiric

biography. “Bohu Esclave Martini.” The case is made by his music throughout.

“What’s the name

of the movie?”

“Donald and Donna Go to New York.”

“Quack. Quack.

Quack. Quack. Quack. Quack. Quack. Quack. Quack. Quack. Quack.”

This is a

specialty of Russell from Dance of the

Seven Veils to Altered States,

applied here continuously. Those people down there looking like ants are real

ants. Russell is in possession of the fact that Martinů is a great

composer facing essential problems in the twentieth century. “Behold the man

who has vanquished the Minotaur!” A Nabokovian theme of exile, horrors of the

war and so on, a mysterious fall. “Is that all you heard, the applause?”

Sanatorium. “The fracture’s mending nicely, it’s no longer a problem...” A

dream analysis, “one must beware of the obvious in these matters.” Lidice. “Now

I’ll tell you about my dreams. It

will make your hair curl!”

Script

and camera by the director. The English Fellini has La dolce vita’s spiraling rise to prepare the Hitchcock Vertigo motif, resolved with a flourish

out of Huston’s Freud in the realm of

Bergman’s Wild Strawberries, to the

tune if you will of Baudelaire’s “Soup and Clouds”, favoring Jelka in Song of Summer (the other half of this

equation from Buñuel’s Cet Obscur Objet

du Désir is by way of Mahler).

Rod

Serling states the case in “A Passage for Trumpet” (The Twilight Zone, dir. Don Medford), the artist’s terrible fall is

not his, per contra, “we have both

risen in my estimation,” Mallarmé tells Heredia after a successful exegesis.

The revelation is a literal one, the Czech ritual of “opening the wells”.

The Insatiable Mrs. Kirsch

Daumier’s Une

Méprise à l’Odéon was formerly presented to English-speaking museumgoers in

Los Angeles as A Wicked Man at the Odeon. The Armand Hammer collection

is no longer at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

What looks like

seaside holidaying to a young writer is actually the woman in the wilderness or

something like it.

Treasure Island