Catherine

Une vie sans joie

A capital work of

art, Dieudonné as cosignatory will have his due, the

photographic reigns supreme, it strides into the cinematographic, his face

expresses the supreme of ennui, the title character is

the mayor’s kitchen maid.

|

Dites,

Edith, un oui qui laisse Votre

soupirant en liesse, Un

oui, par pitié, ou sinon, Malgré

mon zèle je délaisse La

France et l’Administration ! |

As Vigo notes,

there is another Nice, Pabst appears to echo it in Die Dreigroschenoper.

Dieudonné and Renoir continue in a vein anticipating

Pabst’s Tagebuch einer Verlorenen.

The mayor’s

electoral difficulties are a small-town joke writ large and the pivot of the

entire film.

“L’aube

se levait... et Catherine dormait encore.”

The hallucinatory

finish that has “deux vagabonds en quête

d’un mauvais coup” is essentially

mirrored in Murnau’s Sunrise.

La Fille de l’eau

A charming

screenplay, its villain played by its author “entreprit de dilapider l’héritage.”

D.W. Griffith (Broken Blossoms) and Buster Keaton or

Gasnier’s The Perils of Pauline

are indicated, the splendid nightmare is well in advance of Cocteau (and

Russell).

Certain touches

in the shooting and the editing are as much in the vein of early Hitchcock as

anything else.

Pierre Leprohon saw a “partly destroyed copy at the

Cinémathèque Française”, discounted the plot as

“very slight” and described the circumstances of filming in brief

(“the crew set out for La Nicotière,

Cézanne’s property at Marlotte, where various

buildings provided natural settings for the action”).

Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader)

considers the result “full of charm and poetry,” Time Out Film Guide “a quite recognisable Renoir.”

Also Schlesinger

(Far from the Madding Crowd), owing

to Truffaut’s formula, “a woman loves and is loved by three men...”

Nana

“Une jolie

fille... ni voix, ni talent... l’idole du Boulevard... ”

Truffaut,

“romanticism... the same theme as in La

Chienne... Renoir was,

in the view of the profession, just a daddy’s boy keeping himself busy

with a camera and wasting his family’s money when he shot Nana... he reinforced the French side of

his films while he absorbed the Hollywood masters.”

Charles Morgan of

the New York Times found “the

picture is dull... the story itself is a crude one”. It

makes its way through Lang to Kubrick’s Lolita, nonetheless.

Tom Milne

perceives an influence on Les Carabiniers (Godard

on Godard). Truffaut’s amateur has Werner

Krauss to his Comte Muffat, setting off Hessling’s brilliant and fascinating Nana.

“Un échec

retentissant... sa dernière création avait été pour ses amis

l’enterrement de nombreuses espérances.” A resounding failure, the entombment of many a

hope, her Little Duchess (where her success in Blonde Venus inspired Sternberg).

Lively

comparisons can be drawn with Antonioni’s La Signora senza camilie,

Hawks’ Twentieth Century, etc. A most excellent comedy, to be sure.

“Madame est-elle

visible?”

At Longchamps the fix is in, not for long champs.

“The gilded

fly,” she’s called, “that poisons whatever it lands

on.”

Malle remembers Georges “où les robes de Nana faisaient régner un

voluptueux parfum” in Le

Souffle au cœur.

She teaches an

old dog new tricks. “Que les hommes sont bêtes!” Renoir’s contempt for the Théâtre des Variétés is not far from that of Fellini and Lattuada in Luci del Varietà. She dances the can-can like Chaplin’s model for The Gold Rush. The

camera on a dolly deals itself in or out across the set forward or back. “Le plaisir,

le plaisir, si tu crois que ça m’amuse!” It ascends the stairs of Nana’s mansion one

last time with the founder of the feast to see the poor wretch. Minnelli’s Madame

Bovary comes to much the same end.

Geoff Andrew (Time Out),

“anticipates his later (superior) films.”

Sur un air de Charleston

What famous

masterwork did Renoir initiate here?

2001: A Space Odyssey.

Also

Juran’s First Men in the Moon,

Welles’ The Hearts of Age, etc.

“Après vous pourrez me tuer et me manger!”

Reader, she

doesn’t eat dark meat. Vadim’s Barbarella...

“The traditional

dance of White men.”

Truffaut,

“burlesque”.

Tire au flanc

The poet de famille and

the family valet enlist.

Jolly French,

“une note pittoresque dans la vie méthodique de la

caserne: l’arrivée des bleus,” which

is to say that things liven up around the base when recruities

arrive.

At home, a

foreglimpse of La Règle

du jeu. In the barracks, La

Grande illusion. “V’là mon ancien patron. C’est un poseur qui se croit sorti de la ‘cuisine

de Jupiter’ comme

on dit,” the valet says of the poet, seeing

him coming, as they say, “sprung from the headquarters of Zeus.”

At 24fps, a

somewhat intemperate proposition.

“Mon colonel,

c’est le poète.”

“Ah ! oui... l’idiot.”

The title means

goldbricking but has been given as The

Sad Sack, McGrath’s McGonagall is such another.

Truffaut,

“burlesque”, a lesson from Chaplin as Nana from Stroheim, the Renoir theme of the “adorable

hussy”, finally “it is impossible to prove what I believe to be

true—that the construction of Zéro de Conduite (1932), with scenes divided by titles that

comment humorously on life in the dormitory and the refectory, was very much

influenced by Tire au Flanc

(1928), which was itself directly influenced by Chaplin, most particularly by Shoulder Arms (1918).”

Truffaut’s nervous pianist derives in part from the poet’s

guardhouse reading matter, How to Become

Daring. “Most of our politicians are the

living proof.”

Not Solange but

Lily (for the valet his Georgette). Petit ballet du faune et de la sylphide (Georges Pomiès, Michel Simon) with fireworks, a shower.

The colonel is

hoist with his own petard nearly, but Wellies out the

storm.

The poet is victorious. “Qui donc a mis cette brute dans cet état?”

The Tournament

“A

Historical Drama in 3 Reels”, evidently a

fragment of Le Tournoi dans

la cité, reported as twice or even three times

longer.

1562, conveyed by both means available to the

director, a painterly consideration of portrait and pageant, and a purely

naturalistic use of photography for intimate views.

Private duels are outlawed,

one is settled at a public joust.

Catholic and Protestant feuding must cease.

In every way a remarkable film, rather oddly

considered by some writers as insignificant, a commission.

On Purge BéBé

La folie conjugale, familiale, the discovery of the Hebrides.

Feydeau, gone to

town, writes back an explorer’s treatise. The

far-famed savoir-faire and franchise of the French get run up the

flagpole, as the Americans say, “or is that some fancy hat?”

It ain’t

Sèvres, baby. The manufacturer and patent-holder, his luncheon

guest, a highly-placed cocu,

their wives, l’Armée Française et al.

Fulsomely

recalled by Buñuel in Le Fantôme De La Liberté. It ain’t even ordinary porcelain, it’s

unbreakable, “résiste tout... presque tout!”

Time Out,

“droll adaptation of a slight, one-act farce”. Mel

Brooks has the last word, “plumbing!”

The title character is seven, he’s called Toto,

short for Hervé. “Du tout! Du

tout, du tout, du tout, du tout!”

La Chienne

The mystery of

the artist loved for his work.

This is crucial

for an understanding of the double structure set up in Huston’s Moulin

Rouge.

Agonizing, but he

survives, happy in old age with a clochard’s tip.

Boudu sauvé des Eaux

That is, Boudu Saved from Drowning. Renoir’s

sparkling masterpiece is rather, in its literary way, like Nabokov’s

story of the Russian poet long vanished who shows up at a meeting where funds

for his memorial are being collected and cheerfully asks for the money.

Better still,

Enrico’s An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.

The significant

remake is Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills or

Furie’s Little Fauss and Big Halsy.

“And

above all do not go,” says Mallarmé’s almsgiver, “to buy

bread.”

Toni

It’s the

same fate as in La Chienne, set in the air and

light of the Midi, a true story, less comical.

“Renoir

invented neorealism... life as it comes... the work

of the actors in Toni is pure pleasure”. (Truffaut)

Partie de campagne

A film to recall

the director’s father, who said of Mozart, “he had to compose, like

you have to pee.”

Renoir’s

direct corollary to Boudu sauvé des Eaux, and all but a

famous Fragonard.

Sir Toby Belch

and Sir Andrew Aguecheek come and go prosperously, their city scenes were not

filmed owing to production delays caused by rain, it’s

said.

And

this is still, whatever its source, a basis (like the earlier film) of

Renoir’s technique in The Southerner.

Le crime de Monsieur Lange

Arizona Jim

avenges every French writer abused by an editor who deserved dying.

And

thus, even before Coney Island, the Nouvelle Vague begins.

Crowther, a hack if ever there was one, took the occasion of its

first showing in New York three decades later to belittle it, along with

Bresson’s Les dames du Bois de Boulogne.

A film that must

have delighted Hitchcock (Shadow of a doubt) and Huston (Beat the

Devil).

Les Bas-fonds

Decline and fall

of a baron, out gambling with government funds.

Extrication of a

congenital thief, through the love of a good woman.

The flophouse is

run by a fence, her brother-in-law, his wife her sister is conducting an affair

with the thief, and plotting murder.

The good woman is

nearly seized as a bribe by an inspector.

The baron is

infinitely genteel, in his element he is the flower of culture, out of it

perforce he is purblind and does not recognize a blonde’s romantic

anecdote (from a novel called Amour fatale) as reflecting his own

plight, furthermore he punctures an actor’s dream of marble-columned

hospitals somewhere, pristine, for such a drunkard as himself.

Reciting

Shakespeare in the yard, the actor commits suicide by hanging.

The fence is

dead, the thief has served his time, he departs with

the good woman (like Chaplin, as pointed out in reviews).

La Grande illusion

You can see how

grand La Grande illusion is from its various

lines of departure, Dearden’s The

Captive Heart, Bresson’s Un

Condamné à Mort S’est Échappé,

Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai,

and the clearest homage of all, Sturges’ The Great Escape.

The script is an

ascending series of harmonies constructed out of true accounts of World War I,

“the war to end all wars” (that Grand Illusion). Renoir’s

style is all of a piece, an art of pictures, and if the camera moves it’s

from one picture to another.

When Reed takes a

tour of the children’s ward in The

Third Man, he employs a sequence of shots to describe the tragic

scene. Renoir simply pans to Lotte sitting at the

empty table to achieve the same effect. He conveys

Spring by opening a window and dollying through it.

Disney’s The Band Concert and Forde’s Land Without Music may be seen in the

escape scenes, and the sight of Maréchal and

Rosenthal tramping not only must have inspired En Attendant Godot but the opening scene of

Schatzberg’s Scarecrow.

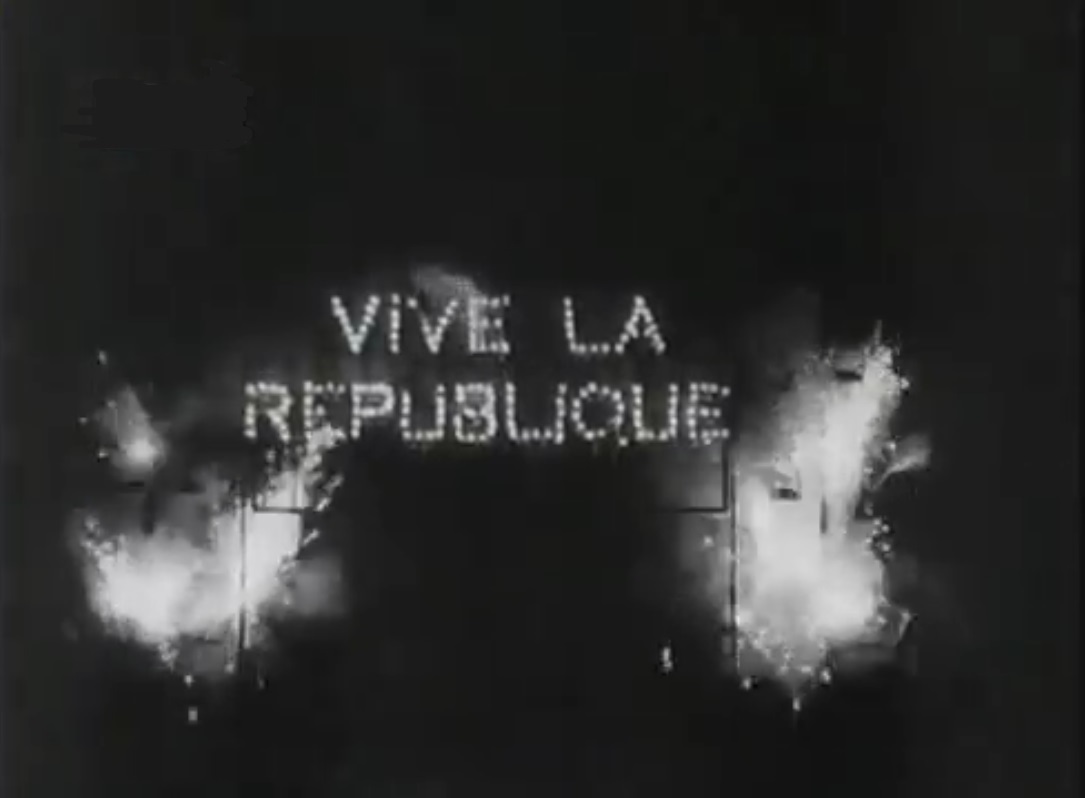

La Marseillaise

From the Bastille

to Versailles, not counting the Reign of Terror.

Renoir is, of

course, on everybody’s side. That includes the

people, which gives some writers pause.

Nothing is missed

or overlooked, and once again the critical perturbation caused by this film is

a fanciful wonder.

It might be an

American war film made a few years later, the men from Marseille are just like

GIs, but it all happened a century-and-a-half earlier, and in France.

La Bête humaine

The film is very

abstract and follows its course like Renoir’s train-rides throughout,

that pass towns and depots right by at a barreling pace and only stop at the

terminus, they even scoop up water en route from pools set out between

the rails.

Grandmorin has had his way with Séverine,

he dies in a railroad car. She tries to persuade Lantier to kill her husband, she dies on her bed.

Lantier then dies beside the tracks. The

extensive citation of Zola given as a preface and reflected in some lines of

dialogue is a preparation. “We’ll teach

you to drink deep ere you depart.”

La Règle du

jeu

It bombed, was

banned, cut and bombed, reassembled, and seen as a masterpiece by Fellini,

Bergman and Buñuel among others, Woody Allen elaborates one of its gags in Annie Hall. It

proceeds from an air du vaudeville

in Beaumarchais’ Mariage de Figaro to Le Bourget and the radio

and telephone. The spécialité de la maison is the curving

track-and-pan.

The ineffectual

meddler Octave is a modulation from Ibsen, and the aviator Jurieu

is twice referred to in terms of Baudelaire’s albatross, an emblem of the

poet. Add the poacher, and Octave’s

self-deprecation as “a parasite” (which was Valéry’s word for

artists and such), and you have the screenwriters’ development of the

comical supporting roles.

It now comes with

a preliminary notice in which Renoir advises the public that it was

“intended as entertainment and not as social criticism,” which

certainly appears to be the case. The original also

was banned, before its triumph.

What you have is

a comedy of manners with a special tinge of satire for the famous, that opens

the flower of Paris and breathes the countryside, and shows all manner of men

and women as charming and ridiculous at the same time.

The theme is

stated with sufficient clarity to avoid misunderstandings. Jurieu crosses the Atlantic and declares his love on the

radio, this is not playing by the rules, but when he does play by them

according to his lights he nearly loses Christine and, thanks to Octave’s

sense of the rules, etc., loses his life.

Analyses have

been made by Alan Bridges in The Shooting

Party and Robert Altman in Gosford

Park.

Swamp Water

The onliest or mainest thing is the

trade of innocence and guilt by revelation. That done, and it’s a mighty simple thing when you look at

it, then there’s the place and folk to consider.

Nicholas Ray gives

an abstract reading in Wind Across the Everglades. Jean

Negulesco countered the reviews with Lure of the

Wilderness.

It might be that

Renoir goes back to silent days for American roots, being here at

“Sixteenth Century-Fox” as he called it.

A snap of his

fingers tells the tale. For the rest, a mighty fine

life, huntin’ an’ trappin’

an’ chasin’ the fox with hounds of an evenin’.

Pierre Leprohon, “Swamp

Water is a good film without an ounce of genius in it. And

this is precisely why the American public gave it such a rapid friendly

welcome.”

This Land Is Mine

HITLER SPEAKS FOR

UNITED EUROPE (headline).

The New Order

comes to a small town in Europe. It explains itself in

the person of Major von Keller (Walter Slezak). This is very edifying, particularly as a number of books

have to be burnt, and several pages removed from textbooks at the school.

A very timid

schoolmaster (Charles Laughton) answers it in the docket for his life on a

charge of murdering a Nazi sympathizer (George Sanders) who has committed suicide.

Maureen

O’Hara is a colleague, Kent Smith her brother in the resistance, Thurston

Hall the hypocritical mayor, etc.

According to Leprohon, “the movie remains indefensible” and

“the best critics (including Bazin and Sadoul)

were provoked into ridicule” because among other things the characters

speak English, which “would not matter, except that the plot and the

spirit of the work are equally ridiculous and false. Renoir

really knew nothing about life under the Occupation, and the American public

took this farce to its heart because it catered to their distorted vision of

the Occupation’s reality.” Renoir to

Claude Renoir (1946), “if what I

read is true, I am not prepared to forget the deep pain this lack of

understanding by my fellow countrymen has caused me... This

incident can only reinforce my desire not to go where I will find men whose

heroism during the war forces my admiration but whose susceptibility seems

regrettable to me.” Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times, “a sane, courageous film... loquacious beyond excuse...

hard to take... hard to credit... far-fetched... too theatrical... dissipates

the interest... doesn’t quite hit the mark.” Variety, “not that the picture is by any means

perfect.” Leonard Maltin, “dated and disappointing today.” TV Guide,

“it

must be praised for its understanding of humanity. Instead

of painting the Germans as mighty evildoers and the French as innocent victims,

Renoir took a more daring and honest approach, implicating the French as being

partly responsible for the Occupation, when many citizens collaborated with the

Nazis to ensure that they would remain immune from punishment and that their

orderly lives would not be shattered by the invaders. Renoir avoided

propagandistic cliches and took into consideration human nature; human nature,

however, is not what people look for in war heroes and patriotic messages.

Although long considered a propaganda film, This

Land Is Mine is more correctly seen as anti-propagandistic. There is no

black and white, no good or evil. There is only grey, and, in that grey area,

an understanding of the frailty of human nature.” Time Out, “unusual ethical stance, not that Nazism was wrong

because it denied free enterprise...” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “pure jingo.” Film4, “moving tirade against Nazism that packs quite an

emotional punch.” David Parkinson (Radio

Times), “throughout the Second World War, Hollywood failed to capture

the fear and suspicion that pervaded occupied Europe. This... is no

exception... bland picture, made with virtually no enthusiasm for its clichéd

villagers and hysterical Nazis, had little dramatic or propagandist

value.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “contrived

plot.” Hal Erickson (All Movie

Guide), “one of those ‘inspirational’ war dramas that

just don’t hold up too well when seen today.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “superfluous flagwaver”,

citing the Guardian, “Zolaesque

intensity,” James Agate, “dull,” and James Agee, “you

cannot afford to dislocate or internationalize your occupied country.”

A Salute to France

Joe Doakes, Tommy Atkins and Jacques Bonhomme

on their way to Normandy, they are each of them any of their countrymen

perchance and much alike (cf. Mervyn LeRoy’s You,

John Jones!), so that in the fortunes of war anyone might hear the charges

read to him, hands bound, once the scourge of “our science”

(“we in Germany have abolished the sterile institutions of democracy

which strangled us. To assert our scientific right to

rule the world, we must wipe out inferior people by every means, by death, by

sterilization, by slavery”) has put out the light of truth (cf. Ken Russell’s Dance of the Seven Veils). The French defeat, another Pearl Harbor and Dunkirk

(“man,” says Tommy, “we never knew what hit us”) and Bataan.

1792

(Rimbaud’s ‘92), 1814, 1870, 1914, Armistice. Pierre

Laval, Jacques Doriot, Oswald Mosley, the American

Bund. “We will wipe out even the memory of your Revolution, and the American, and the British, and the

Russian, the memory of the storming of the Bastille, of the Declaration of

Independence, of the Magna Carta, of the Declaration

of the Rights of Man, the three French Republics, the most dangerous slogan

known to Europe, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity! Now,

for a thousand years, we will decide

the fate of the world... Hail to the New Order! Hail to the superrace!” Blitzkrieg, France overrun. “Soldiers

without uniform... an honest review of our story here in France... but our Pearl Harbor, and our Dunkirk, was France itself. There was no place to retreat, there were no protecting

waters around us, there was no breathing spell, and it seemed to us then, there

was no help, anywhere.” Rejection of Marshal Pétain,

“he told us we were paying for our sins, then he abolished representative

government in France.” De Gaulle in London, “nous croyons que l’honneur des

français consiste à continuer la guerre aux cotés de leurs alliés.” The experience of J.P. Melville, for example,

“when the government began to turn over hostages to be shot,” a

tale told by a priest (cf.

Rossellini’s Roma—città aperta). “I knew there were some things worse than war, and

better than peace! I knew that the Marshal was not our father, but the close relation

of our enemies, and I understood what these three words, Work, Family, Country,

had come to mean.” Resistance to the Occupation,

“a common enemy”. To “the prison

camps of Germany”, a word from “the new French Army”. The Nazi complaint.

“You are on

trial for rebellion against the established order. Your

list of crimes is well-known. You’re one of a

long line of criminals condemned for resistance to invaders for two thousand years—and

for the last hundred and fifty years a wicked struggle. Revolt,

mutiny, arson, propaganda, sabotage, armed resistance, spiritual pollution and

cynical indifference to your lawful masters—these crimes in themselves

are sufficient to condemn you to death; but more than that, your clear record

of continuing to rise and fight again and again—under conditions and laws

of certain defeat—can only be defined as an unforgivable sin. Therefore, no torture, no means of death, no humiliation,

would add up to a just sentence of punishment in such a case; a case without

parallel in history. You stand alone.

There are no witnesses to help you. You may

speak briefly in your own defense.”

Cf.

Beckett’s Catastrophe (dir.

David Mamet), Pinter’s One for the Road (dir. Kenneth Ives). Victory. “The hangman has paid for the bloodshed and the

tears and the sorrow... oh, friend, can you hear—hear the song of

Liberation?” A film summed up by Ken Russell in

the “Mars” sequence of The

Planets.

Claude Dauphin,

with Philip Bourneuf and Burgess Meredith (who also

produced). An extraordinary pirouette that proceeds

directly from This Land Is Mine and

is recollected in Le caporal épinglé, though Renoir modestly dismissed his labors as

a debt owed to America and France, “I worked on this film but I

didn’t make it.”

O.W.I. Overseas

Branch (Philip Dunne, Robert Riskin) assisted by the

Army Pictorial Service and the O.S.S., screenplay Meredith and Maxwell Anderson

and Renoir (using material from Dauphin, serving with the Free French),

supervising editor Garson Kanin (completed by Dunne and Riskin,

Renoir being then in Hollywood for The

Southerner), narration José Ferrer (while playing Iago

to Robeson’s Othello in New York where the film was made), voice of

Hitler and others evidently Paul Frees, score Kurt Weill (whose

“beautiful theme song” recorded by Robeson was cut, Meredith says).

“Next I made a number of short films for the government, to be used to

instruct troops. I don’t know what has become of

them,” vd. nonetheless Tire au flanc.

The Southerner

A portrait of the

Southern dirt farmer. Beulah Bondi’s

unusual performance is an ultimate fount of Paul Henning’s Granny (as

played by Irene Ryan on The Beverly

Hillbillies), and Sam Peckinpah’s The Rifleman owed a good bit of its first seasons to the

neighborly dispute here. The Andy Griffith Show

made comedy of the catching of Lead Pencil, and so did Van Horn’s Any

Which Way You Can.

Renoir’s

close work on the flooded river, though it probably stems from D.W. Griffith,

certainly was a direct model for Boorman’s Deliverance. A distinctive shot

is the tracking shot set off-kilter to the action so that it combines a zoom

and a track. A film so elemental, Renoir was ready

afterward to launch out on The River.

The Diary of A

Chambermaid

Mirbeau in English, by Meredith out of three dramaturges

on the French stage.

The chambermaid

and the scullery maid from Paris in the sticks have their latter-day adventures

behind the oyster bar in Malle’s Atlantic

City, visibly. “He must be a very important man.”

“He’s

a valet!” If the ancien régime family vault recalls the wedding board of The Philadelphia Story (dir. George

Cukor), it is certainly remembered in Big

Trouble (dir. John Cassavetes), the husband is game but the wife has all

the money. The man of liberal thinking lives next

door, eating roses and water lilies and dining with Rose his maid (she calls

him her baby) and lobbing stones into his neighbor’s greenhouse.

The series of

fascinating tableaux (“Fascination” is a theme in the score)

modulates like a development section into the feeble scion and the scheming

valet on Bastille Day. “He’s funny,

isn’t he?”

“Like an

undertaker.” And thus, on a foreign shore, the

director of La Marseillaise conveys

the Terror. “Hm! Here’s another woman murdered in Paris. Another woman cut to pieces.”

“Charles!”

“Yes, dear?” Not quite a year after The Southerner, Irene Ryan herself plays Louise who is such a

lesson to Celestine, the title character. Renoir on a

Hollywood sound stage (“an independent studio that functioned like French

studios, that is,” he explains, “it rented its facilities to

various producers”), directing a major variant of La Règle du jeu with nothing up his sleeves, the only filmmaker who

ever lived than whom Buñuel is not more amusing.

Jacques Becker

recalls it formidably in Casque d’Or. François Truffaut finds it comparable to Le

Testament du Docteur Cordelier. Pierre

Leprohon (Jean

Renoir) records “a series of paroxysms that gradually unloose an

extraordinary bitterness and violence.”

TV Guide,

“a brilliant film”. Leonard Maltin, “uneasy attempt at Continental-style romantic

melodrama... tries hard, but never really sure of what it wants to be.” Geoff Andrew (Time

Out), “it stands on an otherwise uncharted point between La Règle du Jeu and, say, The

Golden Coach.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“wholly artificial and unpersuasive adaptation”.

The Woman on the Beach

An allegory of

the war, lately received as a torso (Time

Out Film Guide) though Renoir is said to have labored a year on the recutting and reshooting, to make it plain in Santa

Barbara.

A nightmare

within a nightmare ends the entre deux guerres (cf. Dieterle’s This Love of Ours).

Tod Butler the great blind artist and his ambivalent

slave of a wife and the United States Coast Guard lieutenant who rides a horse

enact the “dream and danger” before going their separate ways, cf. Richard Wallace’s Thunder Below (with Bickford).

The River

In Bengal,

“where the story really happened.”

The structure is outwardly

like the houses and towns and temples with steps (wide, narrow, rich, poor,

old, new) leading down to the river. Two English girls

and an Anglo-Indian girl who variously live beside the river, to them a

one-legged American wounded in the war.

Already indicated

are the well-informed jokes that go together to make up the actual structure

like a river system.

The best

criticism is in practically any of Satyajit Ray’s films, the Apu trilogy, Pikoo, etc.

The Golden Coach

The dramatic

accomplishment can be simply stated, Renoir makes Vivaldi’s music

intelligible and authentic to our ears, rather than the fodder of classical

music stations. The Cahiers were impressed by

the play within a play, and this is a striking effect when first perceived

after a cut from the opening curtain, the camera shows a theater stage and then

is on a movie set, furthermore a musical effect is achieved when the original

orientation is attained once again at the gift of the coach, a rhyme preparing

the finale, which returns to the stage.

The story is

instantly familiar to a reader of Thornton Wilder or a spectator of Rowland V.

Lee’s film, this is the colonial theater of San Luis Rey, here is the

brilliant actress and the ideal showman, they lead a commedia dell’arte troupe from Italy on a

months’-long voyage to this place, nor far from Cuzco where the Indians

are still being fought. The theater is aptly described

as a “barnyard” with alpacas and the like, the troupe prepares it

festively and puts on a harlequinade for the local peasantry and nobles, under

the auspices of their impresario the innkeeper, whose middle-class friends

can’t be asked to pay, either.

Their passage is

paid by the innkeeper, who expects 80% of the proceeds and a refurbished

theater. The actress’s lover is a soldier

accompanying the troupe, he strikes a fairer bargain, still there is a huge

debt to be paid. The viceroy orders a command

performance.

The polite

courtly response drives the actress to despair, until the viceroy leads a round

of applause. He doffs his wig to the lady in private

(“it itches”), she is most agreeable.

The coach is the

viceroy’s gift to his mistress, a marquise whose husband was sent to the

fighting near Cuzco and died there, the expense is passed off as

“personal expenditure”. To the Council of

Grandees, the viceroy explains it as “a symbol”,

he makes a present of it to the actress, they vote him out of office, subject

to approval by the bishop, “a saint”.

The military

escort joins the army, is captured by the Indians and learns

“they’re better than us”, he

proposes to the actress and offers “a new life” on paths too narrow

for her coach.

The most popular

man in town is the bullfighter Ramon, he proposes as well, they will share

their audience, but he is fiercely jealous, she may not look at another man.

The viceroy

proposes “as an ordinary man”. She is

rueful over his plight, and gives the coach to the Church. The

bishop restores peace, announcing that her gift will carry the Last Sacraments

to condemned prisoners who ask for grace, and that the troupe is to give a

performance at which all are expected.

The

disenchantment of the actress with her profession is conjured away, she returns

to the “two hours nightly” in which she lives.

Since the point

has been missed by reviewers generally, it may be that Renoir made French

Cancan to supply them with a film answering to their assessment of this one

more closely. The point is in the alternatives

symbolically presented to the actress.

The compositions

suit the theatricality of the conception, and Renoir is especially skillful in

his construction of the political side (the grandees are asked for further

contributions to the war effort, and admire the coach). The

English version is very careful to make its points plain, as when the innkeeper

asks the newly-arrived showman how he likes the New World, and the Italian

answers studiedly, “it will be nice when it’s finished.” This is a film of much importance to Renoir, he went

so far as to film it in French, English and Italian. He

has an actor from the Comédie-Française as the bishop, and dubs him into

English for the performance’s sake, as a Mozartean

coda ends all the wrangling among the dramatis personæ.

The impossible

influence on Bergman is marked and notable in The Magician and The

Magic Flute.

French Cancan

Truffaut in his

critical years probably didn’t understand Le Carrosse

d’or, which he nevertheless described as

“the noblest and most refined film ever made,” so Renoir brought

him along with this.

Halliwell’s

Film Guide says it’s

“dramatically thin” but misunderstands the story, not “how

the can-can was launched in Paris night clubs” but how the Moulin Rouge

was launched by Danglard who revived the can-can for

it with a fashionable English name, which is Renoir’s title.

Already the

business is dicey, it gets worse and worse throughout the film, precarious,

precipitous, Danglard literally falls into a pit on

the site of his new establishment, which takes money and talent and brains and

initiative and hard work and genius, and that is why he sits in a chair

backstage attentively at the grand opening, harking to every sound of success.

The great

revelation is just before the final number, the French Cancan, and here the

secret of Le Carrosse d’or

is the mystery revealed. The financial backer and

the admiring prince and the baker’s boy who inherits the shop all have

their part to play, Danglard is the creator of

artistes, he serves them and they serve the theater, that is the only

obligation.

“Each shot

in French Cancan is a popular poster,” says Truffaut, “a

moving ‘Epinal image,’ with beautiful

blacks, maroons, and beiges.”

Alas it is now,

as Time Out Film Guide reports, “digitally restored and on screen

at the BFI Southbank.”

Elena et les Hommes

The secret is so

rare that it will not be disclosed here, except to say that the coup is disguised

as a gypsy.

Prince Volodya desires to blow up the Tsar but destroys himself

and his palace, Lionel gets his Héloïse et Abélard played at La Scala, General Rollan has the nation at his feet.

Henri de Chevincourt, like the great man in Gist’s “I Dream

of Genie” (The Twilight Zone), apperceives where such gifts are

formed.

Truffaut and

Godard praise this film most highly, the former cites

Renoir, “if we leave reality alone, it is a fairy tale.”

Bosley Crowther saw the cut version (Paris Does Strange Things)

and gave it zéro de conduite

in his New York Times review.

Le Testament du Docteur

Cordelier

Good, kindly,

rich Dr. Cordelier, a psychiatrist beset by qualms over his attractive female

patients, gives up his practice to isolate the problem of evil and treat it,

within himself.

The result, M. Opale, is a fascinating herky-jerk

hophead voyou one sees in the city streets now

and again.

Octave serves

this up at the R.T.F., all Barrault, one of

Godard’s Six Best French Films since the Liberation and Ten Best Films of

1961. “One of Renoir’s ill-fated

films,” says Truffaut, “like his Journal d’une Femme de Chambre (The

Diary of a Chambermaid, 1946), which is equally ferocious.”

Le caporal épinglé

The miraculous

effect of its style is to convey and transmute the wartime experiences it

covers with a dash of intimacy and nonchalance that can’t be imitated,

they are quite real and vivid, not so much represented as recorded with a frank

expression to suit the occasion, yet like nothing else on this subject or any

other, certainly not Grand Illusion though it is often cited as parallel

and complementary. And the reason is that Renoir has

invented an altogether new language for his film, which is not made of dramatic

incident and comedy relief, though it has both. The

Fall of France sets a certain sequence of events in motion, these are observed

by following the affairs of a French Army corporal nabbed by the Germans. Lots of things happen and don’t happen, it’s

the story itself that is of maximum interest at every moment, the events matter

in its light. This is one of the great discoveries of

the cinema, one not entirely overlooked but nearly.

Le Petit

Théâtre de Jean Renoir

The end of all

things is le cocuage.

|

the jolly cuckold is a fuck old |

There is precious

little more to be said, the helpful veterinarian arrives in a Volkswagen, the

end comes in the Zone Libre, Renoir emulates

Hitchcock once again (Le Testament du Docteur Cordelier) as compère.