A

Stranger in Town

“The men around here, bless ‘em, either clump

about in gumboots directing dung spreading, or prop up the hotel bar mourning

the nineteenth century. David was cultured, discerning,

and talented, consequently there wasn’t a man who didn’t hate him, nor a woman

who didn’t respond to his charms.”

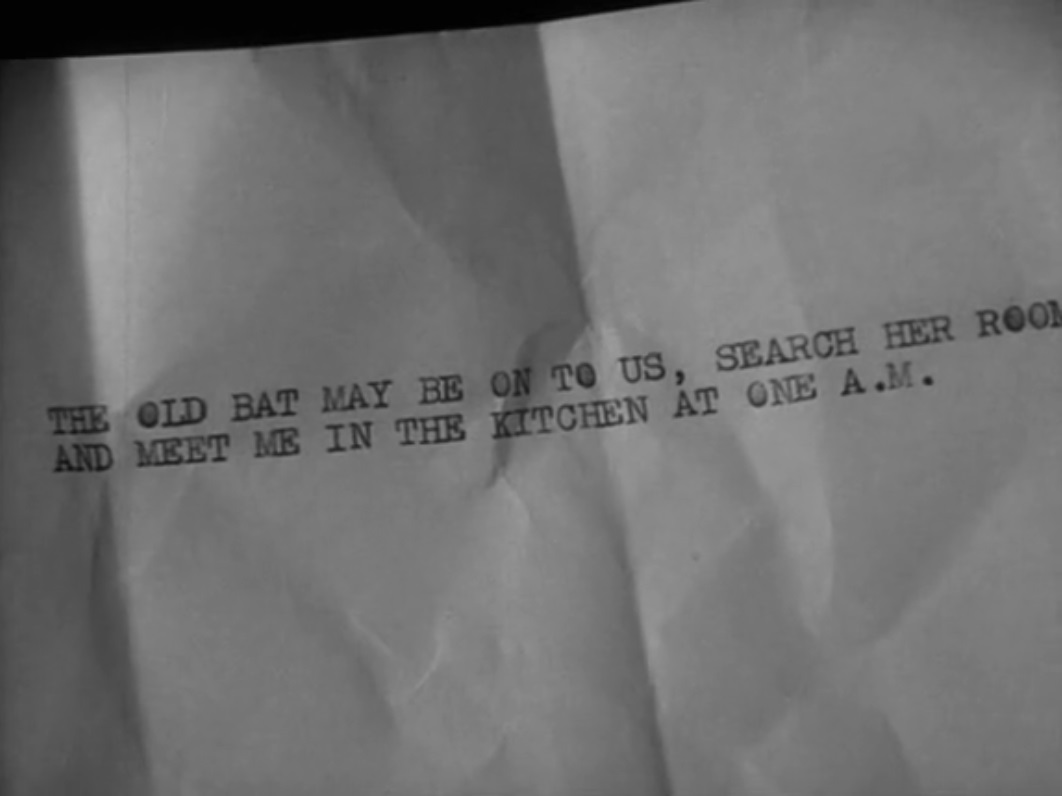

David and King Saul, the story of a pianist-composer

in the sticks, a Yank in an English village complete with bard (parsnip wine,

dabbler in verse, a lady typist by profession), Abigail figures strongly (the shewbread is the bard’s bracelet), he is penurious and

depicted as a blackmailer in villagers’ accounts of him (Vicky had no

inheritance, he threatened to tell Lorna’s husband “a string of lies”, the

farmer’s daughter was too young), dictation laid over a tape of his concerto

identifies the murderer (cf. Douglas

Sirk’s Thunder on the Hill).

A home town reporter on vacation does a job for Uncle

and retraces all the steps, which makes for an interesting structure with doubles

and descriptions (The Third Man is cited in the churchyard scene).

Norman Hudis and Edward Dryhurst have the brilliant, complicated screenplay from a

novel called The Uninvited, Pollock directs on location.

Rooney

“Anything in the paper, Joe?”

“Ah, the whole country’s in a terrible state, lads.”

“Eagh.”

“They say they’re puttin’ up the price o’

stout.”

“And to think o’ the days when it was only tuppence

a pint.”

“Aye, and so full o’ strength that if your glass didn’t stick to the

counter you’d ask for your money back.”

“Ah, there’s no doubt them were the days, we were born out of our

time.”

The Dublin dustman, a prince at the hurling, and the

Cinderella of the premises where he dwells a lodger despised but for his

prospects, like Granddad upstairs who owns the place run by his daughter, a

widow like all them that plague the young fellow with their kindnesses from

pillar to post.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “it is not too

amusing... nor is it dramatically apropos.” Leonard Maltin, “sprightly tale”. Hal

Erickson (All Movie Guide), “stronger

on characterization than plot.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “unconvincing.”

A particularly fine sense of the city (Austin Dempster camera, Christopher Challis cinematography).

And

the Same to You

A very bloody charming comedy on the fight game at shared premises in a

church hall, the up-and-comer’s a boxing blue from Cambridge and the vicar’s

nephew, replacing the house hopeful. Sublimity touches

the screenplay by John Paddy Carstairs when, for

example, the hopeful dances close with Shirley Anne Field.

“Ooh, aren’t you strong.”

“Yeah, but easily led.”

Question of a new roof against deathwatch beetle, also of a very bloody

down-and-out promoter, also of a fixed fight.

“I can’t lose to a new boy. I’d on’y feel like ‘alf a man, an’ that’s no way to feel before y’ wedding, is it.”

“Depends which

half.”

The archdeacon

and Uncle Sidney. “Why does everyone call you Sid?”

“Sheer

popularity.”

How I won the

war, or the thousand pound fight.

Murder She Said

Miss Jane Marple, champion sportswoman, good

English cook, great reader of detective fiction, grand girl all round, enters

the service selflessly when duty calls, as Mrs. Binster

(Richard Briers) joyfully observes.

France turns up again in an Egyptian mummy case amongst the old traps

of a disused outbuilding. Thunderstorm, power failure,

“may I ask what you’re

doing?”

“Trying to provide light.” Dr. Quimper

(Arthur Kennedy) is an American because this is An American Tragedy and a very odd thing, a mirror

to Murder

at the Gallop

as well as in another way The List of Adrian Messenger (dir. John Huston) or Kind Hearts and Coronets (dir. Robert Hamer), “kill off

all your relations in easy stages except the old man, when he dies a natural

death...”

The expert eye will almost certainly discern significant traces of

Cukor (Pat and Mike) and LeRoy (Madame Curie). James Robertson Justice

plays the later John Osborne in the role of Sheridan Whiteside from The Man Who Became the Autocrat of the Breakfast Table.

Pursall & Seddon

screenplay, Geoffrey Faithfull cinematography, Austin

Dempster camera, Douglas Hickox assistant director,

the famous score.

Film4,

“modest and breezy”. A.H. Weiler

of the New York Times, “a thoroughly satisfying and suspenseful diversion.” Variety, “the George H. Brown production is weak in the

motivation area, and there’s a sticky and unnecessary parting shot...” TV Guide, “a bit talky”.

Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “dandy”. Dave

Kehr (Chicago Reader), “distinguished mainly by its

utter lack of atmosphere.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “frightfully British and

disappointingly tame”.

Kill or Cure

J. Barker Rynde (“Jeroboam—I was weaned on

champagne”), Capt., wedding photog cum divorce dick, is hired by a rich

old baggage to put the tail on someone at a health nut hideaway where she,

employer of Rynde, is subsequently poisoned. A reward is offered for blah-blah-blah leading to the

bloke or blokes what done it, our man dives in.

Hook of the long arm comes to this very pretty surmise, “I can feel it,

there’s somethin’ goin’

on.”

“The old head wound acting up, Sir?”

“Yeah, itchin’, itchin’.”

Question thus of a culture war, of some pretty slick doings, finally of

a divorcee with a doubtful past and a nasty character indeed, the secret of

long life is in the end disclosed. “I thought I told

you to get this flamin’ mongrel out of it!”

New York Times, “deplorable slapstick farce... futile pursuit of mirth...

would tax the talents of Charlie Chaplin... a snicker or two from the old

‘health farm’ wheeze... the kind of low-budget ineptitude that even Jerry Lewis

would have spurned.” Britmovie, “mildly amusing comedy”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “flatfooted and unprofessional

murder farce”.

Murder at the Gallop

Old skinflint Enderby dies of a cat, the

heirs are idlers, embezzlers, dabblers in art by and large too stupid to

recognize a masterpiece in their midst, which pretty well defines the critical

position then (New York Times) and now (Time Out Film Guide).

Miss J.T.B. Marple, “a great horsewoman,”

Mrs. Lopsided of Mackendrick’s The Ladykillers to Inspector Craddock (“they’re

really very nice,” she says of the police).

Further and most fantastically, she is an admirer of the authoress,

“Agatha Christie should be compulsory reading for the police force,” and

compares this case to The Ninth Life, a purely fictional work

(“remarkable novel,” Miss Marple calls it).

Screenplay (a nominee for the Edgar Allan Poe Award) by a great

craftsman for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, cinematography Arthur Ibbetson, harpsichord score Ron

Goodwin.

David Parkinson (Radio Times), “but

the most striking thing about this lively whodunnit

is...” Britmovie, “director George Pollock

effortlessly blends clues and comedy”. Film4, “but it doesn't really matter, does it?” Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times, “like taking tea and crumpets with a few cheerful, aging

British friends.” TV Guide, “another mystery romp... such brilliant

performers.” Catholic News Service Media Review

Office, “enjoyable mystery fare.” Eleanor Mannikka (All Movie Guide), “one of a series of competent

murder mysteries”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “a good sense of place and

lively performances.”

Murder Most Foul

Who hanged the actress-turned-barmaid in her flat? A

variant of Murder She Said, acknowledged at the scene of the crime, evidently the work

of a blackmail victim. “What for?”

“Obviously, so that the police would leap to the conclusion they have leapt to.” Notable

jurywoman Marple, an excellent player of draughts who

speaks like a judge and knits like a pearl (“it helps me to concentrate, m’

Lord”), auditions for the Cosgood Players in a Karloffian rendition of Service that wows the char and

hands on stage (the play is Fly By Night, or rather Out of the Stewpot), “these are the simple facts of the case, and I guess

I ought to know...”

They’re playing the Palace, at the Westward Ho! nearby

(“Theatricals Only”) the apprentice actress is ushered in as “your new one,

dear,” and shown to “number ten, upstairs... no male callers”.

Miss Marple is momentarily alarmed by a cat in

her wardrobe, “naughty pussy, what are you doing in there?” Following the murder of a

colleague, she is called upon to play “the Honourable

Penelope Browne, amateur criminologist” in Soho, “London’s square mile of vice,

and worse,” good for the box office.

“Only a woman’s mind,” says Inspector Craddock of Miss Marple’s

latest deduction, “possibly only yours, could have dreamt that one up.” She sums up a modus operandi, “leaving nothing but an

innocent saucepan on the hob,” and this time he concurs, “yes, good work!” The theatrical agent Harris Tumbrill

(Dennis Price) has a tale to tell of old jealousy and poison.

On the night, someone replaces the blank pistol to be fired at Miss

Browne with a banana in the actor’s pocket.

Every stop is pulled out by the screenwriters of Tashlin’s The Alphabet Murders in the expression of a theme

picked up from Hitchcock (Murder!, Stage Fright), Hawks (Twentieth Century), Clayton (Room at the Top, cited jokingly in the

dialogue), and Donen (Charade), not to mention Ron Moody as Cosgood

in a sterling evocation of Kean or Booth or Barrymore

and Mackendrick’s The Ladykillers.

The cinematographer is Desmond Dickinson, director of C.E.M.A. in 1942.

David Parkinson (Radio Times), “rather contrived”. Britmovie, “becomes repetitive despite its

undoubted charm and good humour.” A.H.

Weiler of the New York Times, “a good deal less than exciting

or comic.” Variety, “begins to wear a little thin”. TV Guide, “an

amusing and brainy mystery that does not fail to please... a good British

mystery with enough humor in it to lighten the subject matter, the film is

handled with the seamlessness that director Pollock earlier demonstrated in

both Murder She Said and Murder at the Gallop.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “hasn’t quite found the light

touch it seeks,” by Jove.

Murder Ahoy

Marple in naval uniform, granddaughter of Sir Bertram Marple, Admiral of the Fleet, and niece of the late Rear

Admiral Sir Hubert Marple, aboard H.M.S. Battledore, a man o’ war in service to the

Cape of Good Hope Youth Reclamation Centre, founded by Sir Bertram.

Characteristically fine British camerawork in the laboratory scene (“Slogums Advanced Chemistry Set for Girls”) accomplishes her

analysis of fatally poisoned snuff, not African boxwood, for example (“pity, I

had hopes of that”). In the screenwriters’ finest

joke, she climbs atop her wheeled library steps and calls out, “oh, propel me,

please, Jim,” custodian of the Milchester library,

Mr. Stringer. The Doom Box by J. Plantagenet Corby plucked

from the shelf (among her volumes of mystery and amusement is Two Weeks in Another

Town by

Irwin Shaw, only recently filmed at Cinecittà by Vincente

Minnelli) provides a cognate example of misdiagnosis, a further extension of Murder She Said.

“Look at it,” says the captain of the Battledore (Lionel Jeffries), “reefer

jacket, brass buttons, tricorn hat,” he clucks his

tongue, “who does

she think she is, Neptune’s mother?” His startling

dragon robe (“one thing I can’t stand is being disturbed when I’m curling my

beard”) goes into The War Wagon (dir. Burt Kennedy) with great effect.

Dame Margaret Rutherford, one part Sydney Greenstreet,

one part Maggie Smith, one part Michel Simon, one part Dudley Sutton, one part

Alec Guinness (cf.

Guillermin’s Miss Robin Hood).

Undoubtedly the finest of the four films (pace Halliwell, for whom sequels are

without exception “increasingly poor”), building on the subtle accretion of

theme and inexpressibly benefiting from the wider screen. The

screenplay’s model for one crime (juvenile delinquency) masking another

(embezzlement) is Alfred Werker’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, in all probability (cf. Dassin’s The Naked City, perhaps suggested by the striptease

behind the opening titles).

David Parkinson (Radio Times), “there are too many offbeat characters, a glut of

inconsequential chat and more comedy... than you'd find in the great Dame's

marvellous mysteries.” A.H. Weiler of the New York Times, “rarely exciting, intriguing or

comic.” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “amiable British

mystery-comedy.” TV Guide, “funny, literate and buoyant.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “diluted with

too much feeble comedy”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “all chat and no interest.”

Ten Little Indians

The poetry of Agatha Christie floats in every confession and throughout

the entire structure in a streamlined, very effective version of René Clair’s

original.

Pollock has everything to gain and wins it by painstaking detail in an

Alpine schloß with cable cars, no

communications and a faulty generator.

It’s snow all about, snooker, darkness and fear.

Time Out Film Guide’s loathsome review is a perfect match for Bosley Crowther’s idiocy in the New York Times, likewise Variety.