Uśmiech zębiczny

Toothy Grin

A man leaving his

apartment peeks in a neighbor’s window, a bare-breasted woman is toweling her

hair, her face cannot be seen. He smiles a toothy grin. The door opens, a man in pajamas puts empty milk bottles

out on the landing. The man outside has scurried away,

now returns for a second look. The man in pajamas is

brushing his teeth, the watcher departs for good.

Rozbijemy zabawę...

Break Up the Dance

A gated party,

dancing on the lawn, young people, blues, “When the Saints Go Marching In”, costumes, merriment.

Boys outside

question the host, climb the fence, beat him up, knock his girl down, flitter the place.

Morderstwo

Murderer

Up-angle of a

brass doorplate and handle, a thin vertical intersected. A

man enters the room, kills a sleeping man, departs

closing the door behind him, the opening shot.

Dwaj ludzie

z szafa

Two Men and a

Wardrobe

They emerge from

the sea like Laurel and Hardy in Parrott’s The Music Box (the steps

appear later, taken and abandoned by a drunk), enter the city and are balked at

every turn, streetcar, girl, den of thieves, restaurant, hotel.

Rowdies at an

empty band shell in the park gorge themselves on apples and kill a small

inoffensive black cat, then try to foist the body on a girl waiting for a bus,

but she sees a reflection in the wardrobe’s passing mirror (on the pier’s end,

it serves as a platter for the men’s luncheon of one dried fish swimming in a

sea of clouds). The interlopers get bloodied.

They’re beaten

again when they stop to rest at a barrelyard.

Past Cain and

Abel on the bank of a rivulet below, past a boy endlessly upturning his sandpail to form small mounds on the beach, they return to

the sea.

Lampa

The Lamp

The tenor is

quite close to an American toyshop cartoon in the Thirties, the black-and-white

chiaroscuro is very British, the technique reflects Reed and Hitchcock to some

extent.

Exterior,

toyshop, night. Passersby, an open carriage. The camera dollies in slowly. It

examines the dolls in a leisurely, articulate move, watches the toymaker

putting a wig on one of them by his lamp.

A new electric

light is installed, it hangs naked from the ceiling. After

closing time, the meter with its two side-by-side fuses flares intermittently,

a short ignites the shop, the dolls burn.

The exterior shot

is resumed in rain, the camera dollies out slowly, passersby, a closed

carriage.

The image is

substantially developed out of Picasso’s Guernica (lamp, illumination).

Gdy spadaja

anioly

When Angels Fall

It looks at first

like a leetle memory of Murnau’s Der

lezte Mann, then it blossoms into something that

resembles an anticipation of Tess, and it concludes with a surprising

revelation that later appears in The Tenant.

The old woman was

young, loved by a soldier, he went over the hill

(Visconti’s Senso).

Her cruel son

joined the army, saw horrors, came to a malentendu

with a captured enemy, finally died on the snow with a bullet in his side.

The memories are

in color, presently she sits in a chair and tends a fine old men’s room just

below street level.

An angel crashes

through the heavy glass skylight and greets her.

Polanski appears

briefly as the woman in middle age.

Le gros et le maigre

The old house is

in disrepair, both master and servant wear rags.

Pozzo and Lucky,

but also Laurel and Hardy (Flynn’s Early to Bed) and that goat (Foster’s

Angora Love). Co-directed by Jean-Pierre

Rousseau.

Ssaki

Mammals

Another Laurel

and Hardy short, before their next appearance in Cul-de-Sac.

They share a

one-man sleigh, taking turns as passenger and puller. Escalating

ailments and complaints accelerate the switch (blind, convulsive, headless)

until one has wrapped himself entirely in bandages and they tussle in the snow,

while another man receives the windfall of the sleigh.

Reconciled, the

pair trudge off, till one has a bloody nose and has to be carried...

Ozu’s silent Days

of Youth has its snow gags on a ski trip. Anthony

Quinn says Olivier would tell him, during the stage run of Becket, “I’m

not up to it tonight, you’ll have to carry me,” and then the curtain would go

up and “it was like being caged with a lion.”

The title is

usually rendered in English as Mammals, but perhaps it means Suckers.

Knife in the Water

A 24-hour day,

the Holy Family on a lake (she tends the rudder, he pores over chart and

compass, Jesus dances on his cross—the sequence of shots is from Nicholas Ray’s

King of Kings).

Hitchcock’s Lifeboat

provides the central anecdote and form, with a secondary theme from Huston’s The

African Queen (the sailboat hauled through reeds) and another from To

Catch a Thief (the buoy).

The manner of

filming is of prime interest, recalling the painter-boat of the great

Impressionists, flawless and to all appearances instantaneous.

Pinter’s The

Collection (also Allen Miner’s Chubasco) is

a coherent reflection of the theme. The final image is

of the married couple in Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou. Kafka’s stoker walks

through the film on feet made tender in desuetude.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “all very watchable,

but in a minor key.”

Repulsion

Two murders in a

London flat, committed by a girl who is quite mad. She

works at a salon doing hands, drifts away in the opening scene beside a table

holding a client under a towel with cream on her face and pads on her eyes. The girl has the client’s hand in hers, staring vacantly. The scene is concluded with a joke from H.C. Potter’s Mr.

Blandings Builds His Dream House, the salon is

out of the nail polish requested, “put this on,” says the proprietress, “she’ll

never know the difference.” The feint is on the order

of a lost child holding its mother’s hand.

Presently the

girl is seen ignoring a navvy’s lubricious taunt,

repulsed by her fish and chips at a restaurant, conscious and not withdrawn so

much as blank. The technique is a succession of images

and sounds in continual play, the bell of a convent school across the street

from her sister’s flat, where nuns in white play ball outside, a dish of rabbit

left out with buzzing flies, a crack in the wall that grows in her mind and

multiplies with a roar.

The first murder

is of a nice, genteel young man who courts her in vain. He

breaks down the door, worried about her after days home from work and

unanswered calls. They talk, or rather she turns her

back to him while he talks, he closes the door from the eyes of a neighbor and

she bashes his head with a brass candlestick. The cold

bathwater left from a fit of distraction receives his body.

Her dreams are of

a man raping her, with her back to him. She pulls a

kitchen shelf out and nails it across the door with the candlestick. She and her sister are both French, or possibly Belgian,

for effect. Her sister is on holiday with her English

lover, seeing the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

The second murder

is of the landlord, who comes to collect the rent. She

slashes him with an open razor belonging to her sister’s lover, and upends the

sofa he falls upon. A somewhat older man,

professionally cross until he’s paid, then seductively kind in a general sort

of way.

Hands reach out

from hallways to caress her (Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête), the wall is

soft and leaves an imprint of her hand, the bathroom wall drips like a cavern. In her bed, where she listened vacantly to her sister’s

cries of passion, the ticking clock precedes her nightmares (“is that the right

time”, her suitor asks a barman, who replies, “no

sir”).

A perfect film,

which propounded many things subsequently realized on other terms in Rosemary’s

Baby, The Tenant, Tess, Frantic and so on. The exterior day handheld camera is particularly toughminded and close, following her through the street,

with a variant in Chinatown.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “undeniably effective,” citing the Daily Mail, “a masterpiece of the

macabre.”

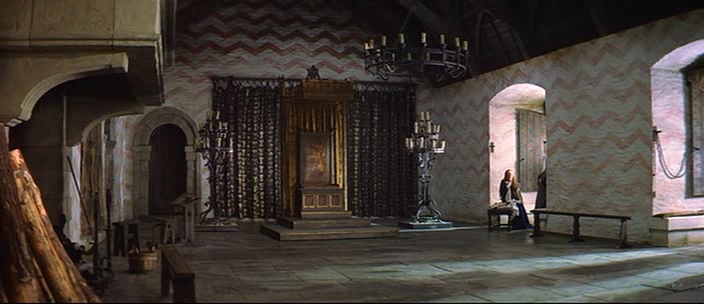

Cul-de-Sac

The tour de

force of the screenplay is a tale told perfectly backwards, a revealed

anecdote. The protagonist has sold his factory and

retired to take art lessons from his new French wife at “Rob Roy Castle” (where

Sir Walter Scott penned his novel) on Lindisfarne,

into which he has sunk his entire fortune after divorcing his first wife,

Agnes.

Sequestered by

the tide, he is cuckolded by the scion of a villa across the bay (“shrimping” is the motif). His

vapid masculinity is ebbed to nil, he is mocked worse

than any Nabokov fall guy in nightie and makeup, his

floozy’s bright joke of an instant.

Two robbers

arrive from a botched job, both wounded, one mortally. An

homage to Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter makes way for a great analysis of The

Servant (dir. Joseph Losey). Peckinpah made Straw Dogs to tell this tale the

other way, a Yank among Englishmen.

Everything

depends upon the structure delivering the void filled by Lionel Stander as the

honest criminal, no explanation is required, desired, admirable or possible

until the very end, when the whole thing comes crashing down and the man is

alone perched on his rock, calling her name who was his woe, “Agnes.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “more perplexing than entertaining.”

The Fearless Vampire Killers

A spectacularly

virtuosic film, treated as a spoof at its first release but actually canonical.

The Count leads a

dance of grave-risen aristocrats who feast on infrequent travelers and likely

villagers. Dr. Abronsius and

Alfred hunt them down by following the clues (wolves, garlic, castle).

The Jewish

innkeeper falls prey, his coffin is excluded from the presence of those

occupied by the Count and his homosexual vampire son.

The innkeeper’s

daughter is seized in her bath and carried off to the castle.

She’s rescued but

too late, she bites poor Alfred’s neck, they drive away through the dark and

snowy night in a sleigh driven by oblivious Dr. Abronsius.

The vertiginous roofscapes of Frantic

are here, also the satanic mystery of Rosemary’s

Baby seen in another light.

The furious sense

of atmosphere conveys the brutal winter of Mitteleuropa

and is very thematic in all its varied, laborious, and exhaustive details

(against which the comedy is a desperate relief), the Count’s vision of evil.

Dance of the Vampires is said to have been the original title, the

midnight ball of morbidly exquisite eighteenth-century revelers includes a dead

ringer for Olivier as Richard III. Komeda’s

score is very brilliant.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “heavy, slow”, citing

Tom Milne, “engaging oddity.”

Rosemary’s Baby

“Debout, les damnés

de la terre...”

Renata Adler of the New

York Times, “one begins to think it is the kind of thing that might really

have happened to her, that a rough beast did slouch toward West 72nd Street to

be born. Everyone else is fine, but the movie—although

it is pleasant—doesn’t quite work on any of its dark or powerful terms.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “but it is much more than just a suspense story; the brilliance

of the film comes more from Polanski’s direction, and from a series of

genuinely inspired performances, than from the original story.” Geoff Andrew (Time

Out), “supremely intelligent and convincing adaptation of Ira Levin’s

Satanist thriller.” TV Guide, “truly frightening because so much of it is so plausible.” Halliwell’s Film

Guide, “well done in a heavy-handed way,” citing the Motion Picture Herald, “may not be for the very young,” and the Daily Telegraph, “tension... surpassing

Hitchcock at his best.”

Macbeth

“All that is

within him does condemn itself for being there.” The

three witches at “The Dawn of Man” (2001:

A Space Odyssey, dir. Stanley Kubrick), and Peter Brook’s shingle (King Lear) or Polanski’s (Cul-de-Sac). Welles

did no more on a Republic sound stage (and with a Scottish accent to boot until

Variety complained) or abroad for Othello. Polanski

has the gift of analysis (cf. Brook’s

other King Lear with Welles, dir.

Andrew McCullough), after the first victory a squall, “so foul and fair a day”

sits naturally as on a horse. Richard Brooks borrows

the first line for Wrong Is Right. The stone steps figure largely in Paul Almond’s CBC

production.

The spectacle is

as fine as Zeffirelli or Preminger or Olivier or

Danny Kaye, the king embracing Macbeth raises the dust of the road on his back. Old Master paintings and Gil Taylor’s Todd-AO

cinematography and illuminated manuscripts are worth so many of even such

words, Polanski weighs them out fairly.

“If the

assassination could trammel up the consequence,” a Chaucer song appositely sung

by a boy, “only vaulting ambition,” the shadow of the crown on Cawdor’s wife, the “dagger of the mind” another vision from

Kubrick (in the “Star Gate”), “it is the bloody business which informs thus to

mine eyes.”

The Last

Supper of Leonardo is brought into

play for the spectacle of Banquo’s ghost (and

Hitchcock’s Psycho etc.), Polanski’s

wizardry of special effects lends a plainspoken truth to lines like, “if I

stand here, I saw him.” A handheld camera again finds

the specter in a wood enthroned with a sunsplash, the

whole scene emanating from Kubrick on the moon, Macbeth who slays himself in

Macduff, Banquo and his Borgesian

mirror-progeny. Russell’s The Devils is more

than kin and less than kind, “baboon’s blood” in Altered States from the weird sisters out of Goya.

Kurosawa’s Ran returns the compliment paid to Throne of Blood, Boorman’s Deliverance

takes note of Lady Macbeth fallen. The material in its

particularly inwrought manner of writing is seen to be very close to Hamlet, “like a giant’s robe upon a

dwarfish thief,” mad scene, flight to England, etc.

“The English

force, s-s-so please you.” Co-written for the screen

by the critic Kenneth Tynan, Wilfred Shingleton designer, fine medieval-sounding score. “Curses not loud, but deep... this petty pace... charmèd life.” And it ends where

it began, like The Tenant.

Variety,

“an admirable try.” Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times), “there seems little doubt that Polanski

intended his film to be full of sound and fury—which it is, to the brim—and to

signify nothing.” TV

Guide, “controversial”. J. Hoberman (Village Voice), “he has no particular

gift for spectacle.” Dave Kehr

(Chicago Reader), “the thematics have

been turned inside out—but that’s what movie adaptations ought to do.” Tom Milne (Time

Out), “never quite spirals into dark, uncontrollable nightmare as the Welles

version (for all its faults) does.” Film4,

“wildly inventive.” Dan Jardine

(All Movie Guide), “an unforgettable

film”. Halliwell’s

Film Guide,

“sharpened and brutalized”.

Che?

Rosebud... Brach and Polanski at a Robbe-Grillet like Hitchcock at

a Bergman.

The girl and the

villa. When you walk among the bittersweet pennyroyals

and magnums, you like to think of yourself somehow amongst the great, with the

mind drifting somewhere in the fields. It has a mind,

which could be the one in Bertolucci’s Stealing

Beauty or Capra’s You Can’t

Take It With You, the villa, which might even be that of Wise’s The Haunting,

but it’s just a lot of exposé and folderol, designed for the purpose of

exploiting the delicate economy of Europe for its point of view, from the

standpoint of an observer many miles away at a checkpoint hearing the orioles

and ortolans passing through the woods, or so he

imagines.

No more than

careless, which is a propos

to be disregarded if you wish upon occasion, and delightfully to be wished, as

necessity or the devil drives.

Alas for Roger

Ebert, who demanded Carlo Ponti’s money back, one of

the most elegant and one of the funniest films ever put together in Europe. “Bacon?” The heroine wants to

know about a splendid painting above the bed. The aged

housekeeper thinks she means breakfast, then slaps the painting but misses the

fly, leaves the room and returns to spray the air vainly with shaving cream.

Out of a dream in

the nether regions comes a Mozart duet and a petal fall’n.

The portraiture

includes a pair of randy rockers in their essential dullness and subterfuge, a

former pimp they call fag and syphilitic (actually mosquito-bitten), Mosquito

the tattooed frogman with a spear-gun and a mustache, Amandine who walks

through scenes quite nude in conversation with a French lady, and Joseph Noblart the host and art patron, dying of artifice. The first inhabitant encountered, after the growling dog,

is mad as a March hare, scurrying about with watch in hand, which gives you Alice

in Wonderland.

The heroine is a

hitchhiker fleeing three Italian rapists, one so purblind having dropped his

glasses he tries to bugger the foremost.

She takes refuge

with her diary in the villa for a time, and only leaves because the film is

over.

Some of

Polanski’s most magnificent effects characterize sleep (on the beach in

moonlight, a snoring house with McGee & Molly’s closet), as later on in Tess.

The moon like a

ping-pong ball from a car on the coast road opens the film.

A priest, an

American tourist-type couple, German businessmen and an art thief with The Raft

of the Frigate Medusa join in the festivities.

The prodigal

daughter returns home with the pigs in the back of a truck, or “maybe Istanbul”.

Chinatown

The hard-luck

case of a San Pedro tuna fisherman who comes home with skipjack, and precious

little of that, not albacore that pays him more, only to find his wife in

another man’s arms and photographic evidence from J.J. Gittes

& Associates, Discreet Investigations (on this score, cf. Schlesinger’s The

Believers). From another point of view, Towne and

Polanski move Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life to the previous decade in

Los Angeles (Chayefsky and Lumet take Meet John

Doe ahead forty years in Network), cf. Pagnol’s Manon des sources, subsequently adapted by Berri

and Brach.

Water is the

absconded needful, Capra’s telling of Job now has a Satan with the redoubtable

and compendious name of Noah Cross, whose relationship to Evelyn and Katherine Mulwray intensively expresses his position on widows and

orphans (figured at Barney’s Barber Shop). The real

Mrs. Mulwray enters like the resuscitated Russian

actress in Sherman’s The Return of Dr. X, her lawyer and the “love nest”

headline are from Citizen Kane. Tribute is paid

to The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep. A

hint of the Dust Bowl and The Grapes of

Wrath (dir. John Ford). The death of Ida Sessions

in Echo Park, an employee of B. Altman & Co. in New York with a Screen

Actors Guild card and a two-dollar bill in her purse, resembles that of Didi in Paris (Frantic).

New York is

governed by witches in the expectation of the one and only Antichrist (Rosemary’s

Baby), Los Angeles on the other hand is “a small town” and an autocracy. “Hollis Mulwray made this city,” says Cross, “and he

made me a fortune.” Polanski’s marshaling of resources

is one of the most impressive feats of filmmaking (he appears as Danny Kaye as

a knife-wielding thug). The title is the place where

“you may think you know what you’re

dealing with, but,” Cross again, “believe me, you don’t,” cf. Mervyn LeRoy’s Escape.

Vincent Canby of

the New York Times, “a kind of criminality

that to us jaded souls today appears to be nothing worse than an eccentric form

of legitimate private enterprise.” Variety,

“it is

easy to speak of Los Angeles’ admittedly prairie metropolis morality and

behavior, but it must be remembered that the swindles and corruption and capers

of the latterday pioneers rank with the worst in municipal rape.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “a tour de force.” TV Guide, “not only one of the greatest

detective films, but one of the most perfectly constructed of all films.” Peter Bradshaw (The

Guardian), “brilliantly shows that money and power are not what’s motivating everyone

after all.” Jessica Winter (Village

Voice), “nihilist ironies collapse atop each other; preemptive excuses are

proffered.” Time

Out, “to beat a genre senseless and dump it in the wilds of Greek tragedy.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “a

superior entertainment”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “pretentious melodrama”.

The

Tenant

A Paris

apartment, hard to come by.

La peinturlure, the one about the late lamented former occupant who

emerges from a closet, the other one about dropping out with a wig on.

Simone Shul, “with a C”, Schul, finally spelled on an envelope, Simone Choule.

Not Weil. The joke from Welles’ The Stranger (as later in The

Pianist) is that Trelkovsky is not French but a

French citizen.

The parody of

Frankenheimer’s The Fixer has him in Simone’s duds at the end (Cul-de-Sac).

These are the

aliquots at least of an introvert’s nightmare, set within the realism of

apartment life (Rosemary’s Baby) and the office (Viollet-le-Duc).

“I mind my own

business,” says the queer in the fancy loft with Poussin’s

L’Enlèvement des Sabines à la Antonioni’s Blowup.

Repulsion, lavatory hieroglyphics, Egyptology at the Louvre,

Gautier’s Le Roman de la Momie, and then the

conclusion that says “you’re next.”

The vaudeville

“crazy house”, cf.

Nichols’ Catch-22, Losey’s Mr. Klein.

“What right has

my head to call itself me?” Cf. Fellini’s “Toby Dammit” (Histoires extraordinaires),

When Angels Fall (Gdy spadaja anioly).

Crabbedness and crassness

have divided the world between them, the protagonist is left darkling.

|

Par délicatesse J’ai

perdu ma vie. |

Rear Window, Le Sang d’un Poète, per contra

“by prong have I entered these hills.”

Vincent Canby of

the New York Times, “movies about

madness tend to lose me after a certain point.” Variety, “it does create a feeling of

personal anguish.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “an embarrassment.” J. Hoberman (Village

Voice), “may be the director’s quintessential movie.” Time Out, “looks more and more like a

potboiler.” Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide), “some critics found the movie tedious and overdone; others

compared it to Polanski’s early breakthrough, Repulsion.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“the total dissipation of whatever talent he once had,” citing Janet Maslin (Newsweek),

“self-parody,” and Kevin Thomas (Los

Angeles Times), “tedium and morbidity.”

Tess

Citizen Kane serves for an entrée, from the opening shot Polanski takes as his formal

departure Welles’ later camerawork. Bertolucci’s 1900 has a comparable theme.

Teresa Durbeyfield, “the last in a line of degenerate aristocrats”, a village girl, is seduced by one Stoke whose family have

bought the ancient name and seal of “a ramping great big lion with a castle on

top.”

She marries a

parson’s son and reader of Marx who longs to go abroad and farm,

he leaves her on their wedding night when she tells him the story.

He returns to her

at a seaside resort where she has become Stoke’s

lover, the murder that follows leads to her arrest at Stonehenge and hanging at

Wintoncester, “aforetime capital of Wessex”.

The sequence of

these events is the main formal pivot of a structure that advances the maidens

of Wessex from the seacoast into a field for dancing. The rowing scene is practically a citation of Chinatown. The

gathering of the wheat... a great student of paintings, Polanski of course,

William Holman Hunt’s The Hireling

Shepherd might be discerned amongst their number. Whey

dripping from bags of rennet suspended in the air is the downstairs sleep of

hands on the farm. Brazil has something of the

significance lent to it in Losey’s The Servant. The milk train to London town (later the milk wagon at Sandbourne). The stag in the woods

at night perhaps recalls Buñuel (Le Fantôme De La Liberté),

almost at once there is Tess at the window one night like the ass of Los Olvidados. The threshing of the wheat... a great house like the

ancient estate of the D’Urbervilles, “To Let”. Much

has transpired before the film begins, the ending is only given as a title. D.H. Lawrence for the something “older than the D’Urbervilles”

on Salisbury Plain. The bitterest remark of all is the

last view of man and wife like Adam and Eve departing Milton’s

paradise.

Nastassja Kinski’s resemblance to

Ingrid Bergman in this part is presumably not fortuitous, on the contrary, the farmyard

scene of “Mrs. D’Urberville’s birds” recalls

Rossellini’s contribution to Siamo donne quite effectively. The

cast are all excellent (Maslin found Angel Clare

“played with supreme radiance by Peter Firth”). Polanski’s

maximum concentration is exerted on the landscape, with the same production

values brought into play as in Chinatown, than which the lighting of the interiors at Sandbourne

apparently proves to be infinitely more complicated.

A plague o’ both

your houses, and the beekeeping vicar who won’t bury the child in consecrated

ground, “that concerns the whole village,” and the rigidly sanctimonious parson. Some considerations are immediately taken up in The French Lieutenant’s Woman (dir.

Karel Reisz).

Janet Maslin of the New

York Times, “a lovely, lyrical, unexpectedly delicate movie.” Variety, “often

has that infrequent quality of combining fidelity and beauty.”

Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times),

“a wonderful film.” Time Out, “a middlebrow film.” Film4, “rather shallow adaptation”. Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “it becomes something rich and strange.” TV Guide, “the

film’s chief drawback, however, is its lack of vitality.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “solid,

unexciting”, citing Sight & Sound, “without a hint of what might have drawn

Polanski to the material.”

Pirates

Le gros et le maigre...

The plain truth

of it is not far from Haskin’s Long John

Silver, with the glory of Australia translated by pirate ships. Flat water, a golden throne on a great harbor chain, and

seated there Walter Matthau, shaggy, frogged and bearded, in the characteristic joke of

Polanski, which Stoppard borrowed once for a gag photo, astride a bicycle with

no wheels.

...Dwaj ludzie z szafa (Two Men

and a Wardrobe).

All of which, by

way of Blake Edwards, is where the staid comedian of the silent films becomes

the hallmark of the Surrealists, who gave themselves a name in lieu quite

handily of provincial blessings from the Fourth Estate, which is no more a

dimension than a Fifth Column.

In fact, nearly

all of the movies on this theme since time began have some representation here,

not excepting Bob Hope and Gene Kelly. Overall, the

game plan (fine-tuned by John Brownjohn) is to pay

homage to Sir Francis Drake, discoverer of the Golden Gate, among other things.

This, then, is a

Hollywood film made without any computer tricks and taking as its substitution

for reality real wooden ships, the Infanta of

Velazquez, and the approach of Richard Lester to the anachronism of time,

proceeding from a sound footing.

The joke is on The Battleship Potemkin

(dir. Sergei

Eisenstein) with Captain Red. “Shipmates! Divine

providence has seen fit to deliver this ‘ere vessel from the tyranny of your

degenerate ‘idalgo masters! I

do ‘ereby take possession of ‘er in the name of the

brethren of the coast, and shall ‘enceforth command

‘er!” And on The

Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as

Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum at Charenton

under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (dir.

Peter Brook). Night among the brigands has a peculiar

flavor of Charles Lamont’s Salome, Where

She Danced that is remembered in Oliver

Twist. The ending suggests Fellini’s E la nave va

and Beckett’s Fin de partie.

Walter Goodman of

the New York Times, “nothing is left

underdone except the hilarity.” Variety,

“a major disappointment.” Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times), “should never have

been made.” Time

Out, “fun intermittently.” TV Guide, “although the film is a bit slow and talky in spots...” Subsequently described by leading professional critics as

“dreary” and “disastrous”...

Frantic

Paris ‘68, twenty

years later, with reference to Hitchcock’s The

Man Who Knew Too Much.

A sufficient

analysis is given in Woody Allen’s Husbands

and Wives.

A quintessential

Hitchcock theme is absence, the ferne

Geliebte or some other person, all is not right

with the world, a falsity is offered in its place, something unsatisfactory,

even antithetical, which is then abolished so that “journeys end in lovers

meeting.”

Another basis of Frantic

is Fisher & Darnborough’s So Long at the Fair

with its false psychological key, actually a memory of the war.

The middle-aged

couple from San Francisco have not been in Paris since June 15th,

1968. Hence their taxicab’s flat tire on the autoroute from the airport, there’s another in the trunk.

Seeing the garbagemen at the back of a truck in town blocking their

way, he knows where he is. And the final image of garbagemen dumping two trash bins similarly seals the deal.

A cautionary

tale, in Paris ist

Revolution ausgebrochen (Alban Berg’s Lulu).

The admirable

formula wings it into the Arab-Israeli conflict, with Interpol and the State Department

just moving on the case.

One of the most

elaborate and minutely-constructed films ever made in the service of a

nightmare.

It opens like Torn Curtain, Dr. Walker is to have

lunch at the Eiffel Tower with Dr. Alembert,

“chairman of the convention”, instead of Mrs. Walker. She

objects, but her husband replies jokingly that Alembert

has been attracted to her since the Berkeley seminar, and she asks if he was

barefoot with long legs.

She’s kidnapped

by Arab agents, he follows her traces with a French girl

who picked up the wrong suitcase at the airport.

It opens and

closes like Fellini’s Roma as

well, and centers not on but around Garnier’s

Opera House, across the Place from Pizza Hut next door to the Grand

Hotel Inter-Continental, etc. The two versions of The

Man Who Knew Too Much get put together by the director of The Tenant,

with a bit of Catch-22 nighttown.

Critics at the

time couldn’t follow it past the first scene, but years later we have all

“followed the affair”, and seen this search for a

Weapon of Mass Destruction (with “collateral damage”) against a backdrop, as

they say, of the Middle East.

Morricone’s

second theme echoes the Danse Infernale of LOiseau

de Feu. John Mahoney is

perched at his fearfully-guarded Embassy desk like Fred Astaire in The

Notorious Landlady.

New York (the

Embassy security office) and San Francisco (the Blue Parrot, the other place in

Casablanca) make a dichotomy, the Blue Parrot and A Touch of Class (a

shiny nightclub standing in for Hitchcock’s Moroccan restaurant) make another.

Themes of

democracy and liberty are touched in a surreal way recalling Russell (the posh

chambermaid, the desk clerk weightlifting at Gym Tonic, the Statue of Liberty à l’envers, etc.). The Krytron caper echoes an

Eighties case involving unauthorized sales to an Israeli firm.

The Long Good

Friday, Bullitt, North

by Northwest.

The meticulous

apparatus of the rooftop scenes is a hallmark of technical precision, briefly

setting out the panoply of Rex Harrison’s battle with the machine in Preston

Sturges’ Unfaithfully Yours.

The same

precision can be seen in the opening, which uncannily reproduces its milieu and

circumstances (elsewhere a connection of this pure Hitchcockismus to Tati’s Playtime

has been noted). Le Grand Hôtel Inter-Continental Paris

(with its Café de la Paix) has since been restored from the sober

makeover visible here, “to its original splendor” and with a Fitness Room of

its own.

Dr. and Mrs.

Walker leave Paris to “go gentle into that good night” (cf. the end of Leone’s Once

Upon a Time in America).

Janet Maslin of the New

York Times, “Hitchcock might have enjoyed...” Variety, “a thriller without much surprise, suspense or excitement.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “it is only the total of the scenes that is wrong.” Desson Howe (Washington Post), “near movie’s end, a

meaty conflict lies unresolved.” Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader), “it’s difficult to care

very much.” Time

Out, “boasts several superb set pieces, even if it doesn’t quite snap shut

on the mind”. TV

Guide, “hauntingly foreign, forbiddingly stylish”.

Bitter Moon

A guide for the

fitfully married, and a literary critique of the horribly bad fiction writer

who mostly tells this tale in flashback. Polanski,

Brach and Brownjohn are at endless pains to give his

prose its just measure of hack squalor. “Nobody would

be tempted to cannibalize my shriveled carcass.”

The title is

first an undrinkable ocean viewed through a porthole at night, later (from the

window seat of an airliner) the moon not shared even when afar.

Silence is most

eloquent, the mating dance over dinner in a Thai restaurant, pictures

unencumbered by the narrator’s verbiage. The wrong shopgirl at the Comptoir

du Pull in Paris. Picasso’s

Salome, Bertolucci’s Partner,

Panama’s How to Commit Marriage.

“The trouble is,

Oscar, publishing isn’t what it used to be, it’s the bottom line that counts

now, proven track records, advance sales. No-one’s

going to invest in a newcomer who hasn’t proven himself.”

In its way, the

dramatic effect is not altogether unlike Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,

here virtuosically achieved in the void of speech between

the ubiquitous stuff of American literary magazines and mere ordinary everyday

commonplace or garden variety utterance. An impression

of women is cultivated with relation to Fellini’s La città

delle donne.

The young

Englishman and his wife (he is “a Eurobond dealer”) on a second honeymoon

across the Mediterranean to Bombay for spiritual enlightenment or marital

therapy are from Hitchcock’s Rich and Strange, and there is a deliberate

allusion to Cacoyannis’ Zorba the Greek. Rear

Window is indicated, briefly. Wyler’s

The Heiress and Gilbert’s Alfie prepare the cruelties and the

nonchalance, La dolce vita is expressly cited at the fancy dress ball on

New Year’s Eve (the costumes bear allusions to the œuvre) en route to

Istanbul. Hutton’s X, Y and Zee foreshadows the

conclusion, to say nothing of Bertolucci’s Il

conformista. Ray’s Distant

Thunder provides an ironic nuance or sidelight.

“Depends on your

state of mind, the way things grab ya.”

“I don’t know

about you,” says the City feller. “Sometimes I think

you make things up as you go along.”

“Just a fantasy,

an amusement on a boring voyage.”

“Did you ever see

such an allegory of grace and beauty?”

Janet Maslin of the New

York Times, “smutty, far-fetched and bizarrely acted.” Derek

Elley (Variety),

“could

have worked if Polanski had established a consistent visual style and dramatic

approach.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “the word ‘lurid’ was coined to describe films like this.” Desson Howe (Washington Post), “Polanski may be off

his creative rocker, but he’s still having fun.” Joe

Brown (Washington Post),

“anti-romantic opus of sexual obsession and cruelty”. Geoff

Andrew (Time Out), “slightly protracted

tale of erotic obsession”.

Death and the Maiden

“After the fall

of the dictatorship” a performance of Schubert’s quartet La Muerte y la Doncella

in “a country in South America...” the doctor’s name is Miranda, the wife’s

maiden name Lorca.

The last shot

resumes the first, couple in the stalls, she looks up to her right at a family

in a box, the doctor is looking down pensively at her.

The flat spare

tire is from Frantic. “That judge who told Maria Batista that her husband wasn’t

tortured to death, no, he just ran off with a younger woman.”

Constellation of Cul-de-Sac (“well, I have a suspicion we

all get a little lost without our wives”). The actors,

even Ben Kingsley and especially Ben

Kingsley as Dr. Miranda, talk American.

“The movement.”

Right-wing

atrocities (The Evil That Men Do,

dir. J. Lee Thompson) and left-wing show trials (L’Aveu, dir. Costa-Gavras) figure

into the thing, with its curious villain not a torturer but a therapist who is

the rapist. “If he’s innocent, then he’s really

fucked.”

The blood of an

Englishman. Kafka’s pair of detectives. “Were you in love with her?” Cf. Fuller’s The Naked Kiss, “I loved it. I was sorry

it ended. I was very sorry it ended.”

Caryn James of the New

York Times, “brilliance with the camera turns Ariel Dorfman’s well-meaning but

pretentious play about human rights into a harrowing experience.” Todd McCarthy (Variety),

“any significant reservations about it must stem from

the material itself.”

Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times), “all about acting. In other hands, even given the same director, this might

have been a dreary slog.” Hal Hinson (Washington Post), “yeah. And monkeys might fly out my bottom.” Desson Howe (Washington

Post), “too contrived and smug to really hold.” Geoff

Andrew (Time Out),

“allows

for a fluent, lucid exploration of notions of justice, responsibility,

forgiveness, and corruption by power...”

The Ninth Gate

Roy William

Neill’s Dressed to Kill is the patent model for this (three almost

identical music boxes there, three books here), a comical Russellian

biography of Dr. Johnson in the form of a Holmes and Watson. The

subject of the present biography is Satan (Baroness Kessler is writing just

such a work, which is “to be published in the Spring”).

Polanski’s

contribution to film noir includes the realization that, boiled down and

hardboiled, Satan is the character in many a movie who tempts with forbidden

knowledge or worldly emolument or great affliction, always wrestling with a

good angel (and often making a surprise reappearance) at the end.

He, that is to

say the Devil, is Lucifer, “son of the morning”,

liable to appear (as at the close of this film) in the guise of an angel of

light.

Elvis Mitchell of

the New York Times, “a dinner-theater

version of Eyes Wide Shut.” Lisa Nesselson (Variety), “really

a shaggy devil story whose giddy, ironic tone may throw viewers expecting a

scary movie.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “only gradually do we realize the movie isn’t going to pay off.” Stephen Hunter (Washington

Post), “utter spewing mewling nonsense.” Peter

Bradshaw (The Guardian), “this really is an

exasperatingly boring film, and it is incredible that it is from the man who

long ago brought us authentically frightening films in which evil really means

something.” J. Hoberman (Village Voice), “barely releasable

hokum, stuffed with cheesy blah-blah.” Philip Strick (Sight

and Sound), “seems at a loss what to make of a demon who bleeds like everybody else and

reads How to Make Friends and Influence People.” Geoff

Andrew (Time Out), “a pale shadow of Rosemary’s Baby.” Maitland

McDonough (TV Guide), “what a tedious

film.”

“WARSAW 1939”.

In the

early days of Technicolor, Graham Greene wondered if it really could be used to

depict the seedy suit, the sweat-stained hat. Szpilman escapes from the Warsaw Ghetto, is taken to an

unused apartment, and there beholds a nice clean sofa like a desideratum of

bliss, an island in a sea of schmutz, just the

fabric and the comfort of it, without any particular emphasis.

From the first

scene, Polanski is on new ground (Chinatown, The Tenant, Frantic,

all had to be made first, for this to exist). Szpilman is calmly playing Chopin in a Warsaw Radio studio

when the bombs start falling. First the window in the

booth is shattered, then it’s imploded.

What follows is a

different film. Where he had begun way out ahead of

everything with a characteristic Hitchcockism,

Polanski now must return to square one and the basic incompetence of Schindler’s

List. This is heroic, somebody had to do it. Scene by scene, each scene is brought to the limits of the

possible, and left with a definition somewhere in its depths (Father stepping

into the gutter, Szpilman’s little hand gesture as he

waves off the piano). Much later is an oblique

reference, one might think, to a filmmaker one feels has profited from other

people’s misfortune (Godard says Mrs. Schindler never received the money

promised her for Spielberg’s film). The point of

departure is Doctor Zhivago.

Polanski’s art in

a larger, strategic or formal sense, has to find a valuable means of

articulating a film on two levels at once. Again and

again, he returns to the mark set at the opening, in battle scenes bristling

with photojournalistic accuracy.

Perhaps it would

be easiest to regard The Pianist as a memoir faithfully filmed

incorporating a response to two films of titanic ineptitude, the other being Saving

Private Ryan. Polanski has his own tale to tell,

and there is The Painted Bird. It seems a noble

gesture to have made this particular film.

The articulating

point is taken from Welles’ The Stranger, “who but a Nazi would deny

Marx was a German, because he was a Jew?” This becomes

a film about Poland and especially Warsaw (Szpilman’s

memoir was originally entitled Death of a City). Essentially

it’s a “mille fleurs” pattern, a picture of

this, a picture of that, leading to the progressive revelation of music as an

art.

The ghetto is a

ridiculous traffic jam at first. While waiting to

cross the tracks, Jews are requested to dance. “Judentanzplatz” is what a German soldier calls it. In the ghetto cafe, Szpilman’s

playing is interrupted by a customer who wants to test gold coins on his

tabletop, dropping them and clinking them one by one, till he hears a dud. The grandest scene has Szpilman

alone in blocks of bombed-out houses, finding a last refuge in an uppermost

attic nook. He is discovered by a rather laconic

German officer and obliged to play for him. At this

point, the actor Adrien Brody had actually lost much

weight, his hair and beard are overgrown, his hands appear gnarled (his facial

expression and the sound he makes when, stiff with inanition, he is forced to

jump out a window, are uncannily true). Nevertheless,

he sits down and opens with parallel octaves, warming into Chopin’s bubbling

rivers of voices and music, an all but articulate speech, and Polanski doesn’t

miss a note of it. The officer is moved. Later he brings food, and finally gives Szpilman his overcoat. But this

only prepares the next scene. The Russians have

entered Warsaw. Seeing Szpilman

the bearded Christ in a German officer’s overcoat, a Polish woman shouts

“German! German!” (just as

another earlier had shouted “Jew! Jew!”) and the Russian troops start taking potshots at him. “Don’t shoot!”, he says, “I’m Polish!” “What’s

with the fucking coat?”, says one of them. Szpilman replies, “I’m cold.”

And before you

know it, he’s back playing the piano for Warsaw Radio, looking a good deal like

Horowitz (one photograph of Szpilman suggests a

resemblance to Jack Benny in To Be or Not to Be).

The sound editing

registers the halting small-arms fire in the street turning into a more assured

avenging burst, the unforgettable sound of troops marching across a cobblestone

square, bombs, artillery fire at such a distance, the nuances of the

performance.

Contemporary

footage at the outset gives another mark Polanski aims at and returns to

several times (rather than dissolving from, etc.). The

German officer is introduced rather shockingly with the famous shot at the end

of Peter Brook’s Lord of the Flies. As Szpilman plays, that shaft of light athwart the dark studio

at the end of Fellini’s Intervista plays over

the piano. Warsaw at night, blue and inviting, after

the horrors of the ghetto. Szpilman

wandering the ruins, like Keaton in The Navigator.

A.O. Scott of the

New York Times, “a monstrous joke.” Todd McCarthy (Variety),

“a remarkably conventional film... a decent B.O. attraction.”

Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times),

“Polanski is reflecting, I believe, his own deepest feelings.”

J. Hoberman (Village Voice), “suffers from over-explanation.” David

Thompson (Sight and Sound), “a work of sustained

tension and ferocious clarity.” Geoff Andrew (Time Out), “old-fashioned in both visual

and narrative style and in its overall restraint.”

Oliver Twist

Another view of Tess.

Polanski has put

his film of Dickens on a sound dramatic footing, that is his practice, first mise en scène, then

cinema.

This gives

extraordinary force to every bit of it, because it’s all thought out to the

last degree (note the loose end from the Beeb intact

in Nancy just for sheer larks). “Mysteriousness” is

not in the picture, there’s no terra incognita. Overall,

the clarity of sense thus given to the piece or revealed in it makes Oliver

Twist a fair mirror of the times, and Gustave Doré is called upon behind the end credits to show us

Dickens’ day.

Signs in the

workhouse refectory read, GOD IS HOLY, GOD IS TRUTH and (just before Oliver

goes to ask for more) GOD IS LOVE, which is like the American joke, In God We

Trust, all others pay cash.

Polanski’s

caricatures include a Sowerberry who looks like the

Child Catcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Oliver’s turn as a

“funeral mute” encapsulates a famous scene in Miracolo

a Milano.

The sheer misery

of the workhouse is left behind for London 70 miles away, the camera cranes up

for the journey past the old woman’s house like England in the seas, with a juggernaut

of townsmen on the road, to the merry world of Fagin, merry amidst the mildew. Ben Kingsley modulates the role visibly in three quick

steps, from Paul Scofield to Bernard Miles and thence to a somewhat unexpected

rarity, the fairhaired boy with a workhouse of

industrious lads and a bright demonstration of “the game”. He

almost murders Oliver for spying his treasure, but doesn’t after all.

A certain

advantage is the revelation of character provided by dressing the scenes so

that, for example, Bill Sykes hangs himself in an escapade under the moon,

delivering Oliver’s benefactor Mr. Brownlow into the

safe hands of identifiable personality, the gentleman of good will in a

disordered world (the scene incidentally clarifies the ending of Hitchcock’s Jamaica

Inn, if clarification were wanting).

One of the

greatest films ever made, you might tell your digital grandchildren, came and

went without anybody really noticing, as sometimes happens, look at Citizen

Kane, by all means.

A.O. Scott of the

New York Times, “at every turn he is

menaced by adults whose grotesqueness, while comical, is also a measure of

their moral deformity, and of the ugliness of the society that makes them

possible. The worst thing about these villains, who

tend to occupy positions of at least relative power, is that they believe their

sadism and lack of compassion to be the highest expressions of benevolence.” Todd McCarthy (Variety),

“conventional, straightforward and very much within

what used to be called the Tradition of Quality, this handsome film is a

respectable literary adaptation but lacks dramatic urgency and intriguing

undercurrents.” Roger Ebert (Chicago

Sun-Times), “this is not Ye Olde London, but Ye

Harrowing London, teeming with life and dispute.” Jessica

Winter (Village Voice), “the quality

of mercy is strained, but by some strange feat it doesn’t dissolve entirely.” Peter Bradshaw (The

Guardian), “a handsome repro edition—much like the expensive octavo volumes that Oliver

is fatefully charged by Mr Brownlow with delivering to London—bound in

celluloid calf and lightly sprinkled with the picturesque movie dust of Old

London Town.” Time Out, “Polanski presents a threatening, rotten world as viewed

through the eyes of a vulnerable innocent; he tackles jealousy, suspicion and

corruption as surely in storybook mode as through suspense, investigation or

horror.”