Paris After Dark

The Occupation. Dismantled factories, expatriation, forced labor. “After all, what does France need industry for? We will produce for the whole world! The rest can go back to the land.”

“You’ve planned for everything, haven’t you.”

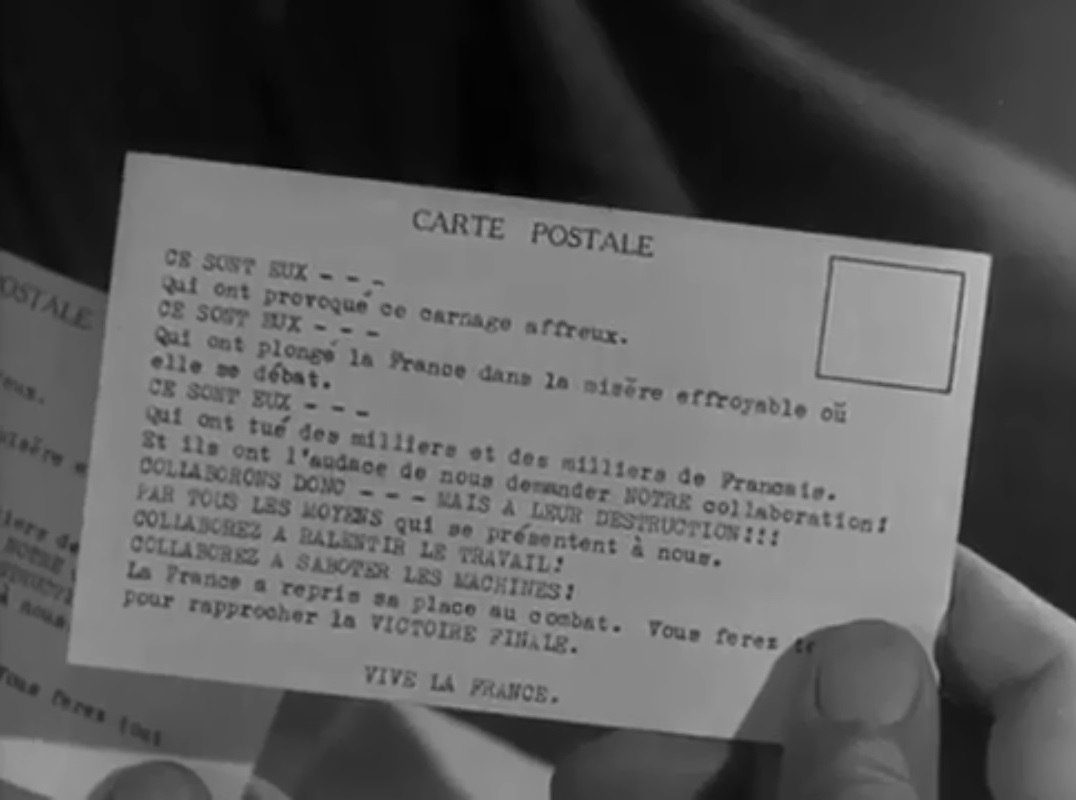

“My dear Marbel, that’s the meaning of leadership.” A French film made in Hollywood, Robbe-Grillet’s soldier back from the defeat to the soup bone that lasts a week, Resistance leaflets, fear and death, “the only ones who don’t know fear haven’t fallen into their hands yet, otherwise they would have fear too, and curse themselves for not making peace when they could.”

Usines Beaumont, a place of sabotage (the opening location for Abbott & Donen’s The Pajama Game, remembered at the start of Frankenheimer’s The Train). The greatest joke of the war, “well, a German meets a Hollander, and the German says, ‘heil Hitler!’ The Hollander says, ‘heil Rembrandt!’ The German says, ‘why do you heil Rembrandt?’ The Hollander says, ‘because Rembrandt was OUR best painter!’”

Question of operating on a badly wounded colonel in command, “does it matter that you are French and I am German?”

“Only you Nazis have raised that question.”

“Don’t let me die, for humanity’s sake,” cf. Rod Serling’s “The Obsolete Man” (dir. Elliot Silverstein for The Twilight Zone). The eminent surgeon, a Resistance man, asks for the lives of fifty French hostages. Death of an informer. “The criminal is believed to be a member of the so-called underground, which is nothing but a small group of Jews and Communists.”

“In matters of crime, the Nazis are experts.” A certain homage to Asquith’s Freedom Radio.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “a stilted melodrama which is both graphically and emotionally dull.” Tom Milne (Time Out), “stock WWII tub-thumper about the need for resistance to Nazism.” Leonard Maltin, “preachy but effective melodrama”. TV Guide, “Moguy gives this film a good sense of direction.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “hokey World War II morale booster”. Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide), “French Underground melodrama”. Halliwell’s Film Guide (as The Night Is Ending), “propaganda potboiler.”

Action In Arabia

“The new saviors of Islam—the Nazis,” buying Syrian camels by the freightload. American newspaper reporters recalled from Iran in 1941 chance upon the story, one is “killed, and in a camel market,” cf. Marcel Ophuls’ Veillées d’armes. The business of such men is drolly conceived as a kind of inquisitive wonderment. “I think you’d better ask Uncle André himself, French diplomatic officials don’t like questions answered by unauthorized persons, especially these days.”

“In these days, French diplomatic officials don’t like questions, period.” Any recognizance of Curtiz’ Casablanca is a jumping-off point. “How did you know?”

“You shouldn’t claim to have read ponderous political books which exist only in my imagination. But it was a pretty good title though, wasn’t it, The Theory of Political Unity.”

A formidable screenplay by Philip MacDonald and Herbert Biberman undergoes the spellbinding treatment of a director who understands the cinema as rarely. George Sanders gets off the plane in Damascus and walks to his hotel, the camera accrues an impression along the way that is more than photographic. The glint of Gene Lockhart’s cigarette case in the sun appears fortuitous and untoward until Sanders tries the trick to signal Robert Armstrong of the Foreign Service. “What will happen if I should encounter some wandering savages?”

“Just don’t sell them the plane.” Lean remembers the plane and the reporter and the French diplomat and the tribes’ “spiritual leader” and the whole bloody business in Lawrence of Arabia. “It is written that wisdom and passion cannot exist together, release him.” Crowther titled his review “Gordon of Arabia”, and indeed it suggests Dearden’s Khartoum in more than one respect. “Reliable inside information.”

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “buncombe... pleasant buncombe... purest buncombe.” Leonard Maltin, “OK drama”. Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide), “patriotic thriller”.

Whistle Stop

The crucial date for any expatriate is given at the railroad depot of the title, June 1940, printed on a calendar. Ashbury, west of Detroit, Chicago it ain’t, that metropolis of department store moguls. John Huston has a great and cultivated appreciation of the ambience in Fat City (and the latter end of The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean), Orson Welles greatly amplifies the brief car chase down a long alley in Touch of Evil.

The plain difference between the annual fair that might have ended the life of a well-heeled blackmailer lording it over the Flamingo Room, and his bizarre plan to rid himself of opposition.

Moguy after the war regains his composure, smoothes his hair with one hand and runs a taut ship with the other, deep within the dream.

Philip Yordan screenplay from the novel, Russell Metty cinematography, Dimitri Tiomkin score.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “this plainly remote and artificial concoction lacks flavor, consistency, reason and even dramatic suspense. And it is also abominably acted—which covers about everything.” Variety, “production and playing are excellent and the direction strong, although latter is given to occasional arty tone.” Leonard Maltin, “unusually stupid Raft vehicle”. TV Guide, “a second-rate gangster film with a fine cast but no spark.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “unrewarding”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “would-be film noir.”