The Spiders

The Golden Sea

The influence of

Gasnier’s The Perils of Pauline

is very striking.

Professor Johnson

of Harvard, kidnapped by “descendants of the Incas” while exploring

in Peru, their fabulous wealth. The enchanting style is played directly to the

camera at times. The Standard Club of San Francisco, a gallant yachtsman, the

America-Japan Regatta.

Feuillade for the

Spiders. Bigwigs, financiers, with ninja cadres, after the gold.

“The two

expeditions prepare.” In Mexico, a Western by Griffith or Hart. “A

mysterious diamond ship.”

Question of human

sacrifice. The Priestess of the Sun.

Vivid memories

are to be found in many a film, Robert Day’s Tarzan and the City of Gold is one, J. Lee Thompson’s Mackenna’s Gold another, the death

of Naela in This

Sporting Life (dir. Lindsay Anderson).

“Riotously

exotic... a demonstration of the aesthetic power of popular culture” (Film4). Tom Milne (Time Out) speaks of “Lang’s superb architectural

sense.”

Harakiri

This is all

worked out from Madama Butterfly, a teddy bear earns the Daimyo

ritual death from the Mikado at the behest of the Bonze, who places the

suicide’s daughter (recipient of the gift) in the Sacred Garden broached

by a foreign captain, who marries the girl for a time.

A beautiful

masterpiece, a great Japanese film, every inch worthy of its source, and now

extant in a lone Dutch print.

The Spiders

The Diamond Ship

“Our

biggest secret.”

Before F. Richard

Jones’ Bulldog Drummond, a love

of trickery and gadgets in the villains.

“The lost

stone.”

“A modern

raid.”

“The secret

of the many diamond thefts.”

The ivory key.

“In the

subterranean Chinese city.” Gambling and opium at the Red Dragon.

The diamond of

the Buddha head. The low dive of Vier um die Frau.

The Storm Bird, sailing for South America.

Yoghi All-hab-mah, seer.

The diamond that

will free Asia. A London trader. A pirate captain of the sixteenth century,

“the logbook of the Sea Witch.”

Ahead of

Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps,

“Four-Finger John”. The Falkland Islands. “The treasure

cavern.” “The poisonous crater.”

A duplicate

stone, to be carved in Amsterdam for “the Asia Committee”.

The Secret of the Sphinx and For

Asia’s Imperial Crown, unfilmed (except as The Tiger of Eshnapur and The Indian Tomb). A certain Londoner has

held Asia in thrall for half a century and more, in that sense a prophetic

film.

Das Wandernde Bild

The Virgin of the

Snows is seen to tread the earth by a hermit who has left his wife according to

his worldly antipathy toward marriage, he returns to her, a woman plagued by

jealous heirs to her husband’s fortune.

Thus much can be

gleaned from the Cinemateca Brasileira’s

incomplete print, said to be the only one in existence.

Vier um die Frau

Five characters in all.

Harry Yquem, a fabulously wealthy stockbroker who uses

counterfeit money and a disguise to buy a stolen jewel for his wife.

Florence Yquem, née Forster, who married according to her

father’s wishes.

Werner Krafft, whom she had loved.

William Krafft, his brother, a high-class jewel thief.

Charles Meunier, a blackmailer.

The complications

are as ornate as any farce, but at the end Meunier is

dead, Harry and William are under arrest, Florence is wounded yet still

proclaiming her devotion to Harry, who loves her so.

Again (Das Wandernde Bild), the Cinemateca Brasileira has the

only print.

Der Müde Tod

The greatness of

this, the vernissage, occurs at the point of

conception and is left intact to be found at the end, when the spectator in his

seat in the theater is Fritz Lang. This is the creative distance that would be

what Brecht has in mind, the stories read by gentlemen of the country “in

the light they have invented,” and there are no witticisms that can

improve on that.

Lang’s

technical artifices are not ideal (ninety percent is the best he could

achieve), but the aplomb of their usage carries dramatic weight effortlessly,

so that if the effect must be employed, it justifies the frames of its

existence. The Junge Mädchen

takes a draft that transports her to the realm of Death. Lang quickly dissolves

on her in the same position but not precisely, and the momentary inconstancy is

what creates the transition, dramatically. Death (an avatar of the

Mephistophelean one in The Seventh Seal) is God’s executioner, and

would bless the lady if her love could overcome him. Human lives are tall thin

candles snuffed out when the Lord wills it. Death’s hands somberly

approach the candle flame and lift it (via jump cut) from the wick, it

is a baby in his arms (the dissolve), and then it is gone (Lang cuts to the

mother weeping over its corpse on Earth). The conception, realized in

Lang’s technique, is that of lives watched over by Death and ultimately

passing through his hands and beyond him. Keaton’s magic and the M-G-M

wipe of invisibility are not cinematically superior.

All this is but a

metaphor. Would she win her beloved back from Death, the Junge

Mädchen must keep three short candle flames lighted, or one of them at least.

The scenic

conception of this is faultlessly imaginative. At the back of a vast hall is a

tall Gothic doorway through which stone steps can be seen rising to infinity in

a graduation from dark to light. In a long shot of the doorway (there is naught

else in the image), the Junge Mädchen

climbs the stairs and thus rises to the point of the doorway arch.

Death’s chamber of tall tapers is constructed of their slightly

off-kilter or akimbo verticals in darkness, rather

than dominated by their illumination.

She seeks to

reclaim the Junge Mann from the walled domain of

Death.

The three lights

are those of a Frank in the Caliph’s court (he loves Zobeide),

a Venetian swain whose Monna Fiametta

is betrothed to Girolamo, and a magician’s

assistant in China whose beloved is claimed by the Son of Heaven.

The 2000

“edition” by Film Preservation Associates is tinted but shortened

and so choppy as to be unserviceable.

Dr. Mabuse der Spieler

“A good

average popular thriller—dime novel stuff in a $100,000 setting—but

sufficiently well camouflaged to get by with a class audience,” thus Variety

of a version one-fourth the original length, presumably with reference to

Feuillade.

Mabuse spins the

stock market into a crash and rises from it wealthy, he hypnotizes fellow

card-players into throwing away their hands, he

projects his will onto a count to make him cheat, and takes the swooning

countess to bed.

“What do

you think of Expressionism, Herr Doktor?

“It’s

a pastime, like everything else nowadays.”

Death to the

mistress thought disloyal, death by snake venom.

Death to the

count, by auto-suggestion. Death to State Attorney Von Wenk

the same way, in front of a crowd of people at Philharmonic Hall, his men save

him.

Dr. Mabuse, gambler,

psychoanalyst, is also Sandor Weltmann

the charlatan.

He goes into

early Hitchcock, especially his wild shootout with the police and the army (The

Man Who Knew Too Much).

He is trapped

amid ghosts, quite mad, within his counterfeit printing house run by blind men.

Herzog rememorates him for Invincible.

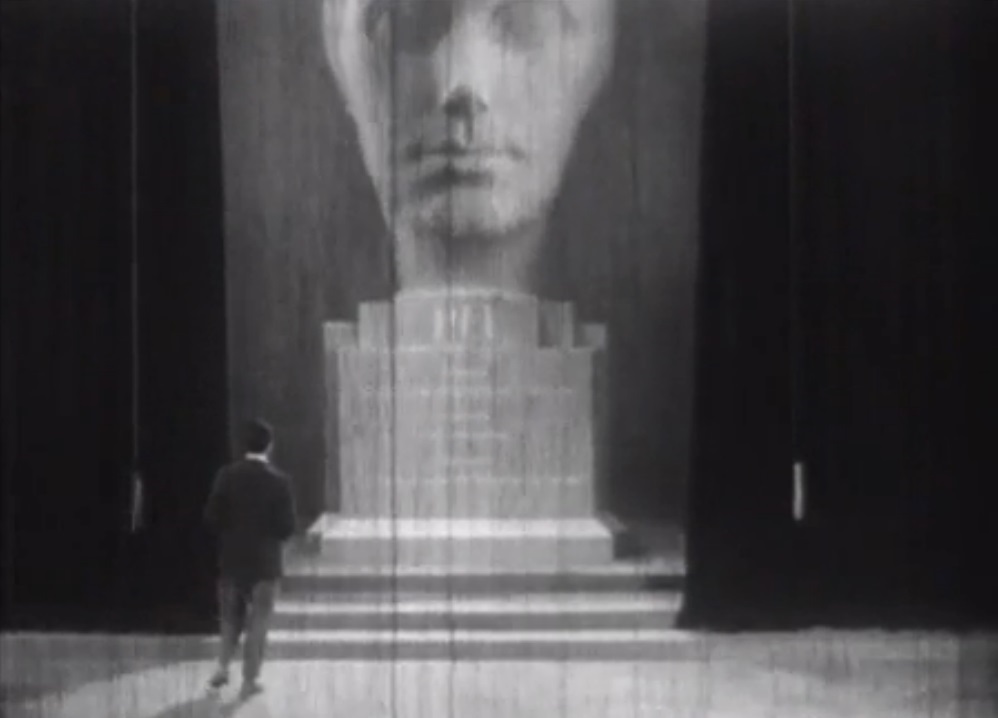

Metropolis

The emperor and

the nightingale.

Moloch, Babel, Die

grosse Babylon...

Griffith’s Broken Blossoms, Worsley’s

The Hunchback of Notre Dame...

Chaplin’s Modern Times, Godard’s Alphaville, Pal’s The Time Machine, Menzies’ Things to Come, Rosenberg’s The Drowning Pool...

The restoration

by Kino, the Murnau-Stiftung, the Bundesarchiv-Berlin

and an impressive list of cinematheques around the

world, if projected at the wrong speed, renders the film absurd. It

nevertheless has Gottfried Huppertz’s

magnificent orchestral score, mocking the impossible result.

Certainly, Metropolis

anticipates this revolting development. A prophetess named Maria awaits the

Mediator who shall reconcile the worlds above and below, but she is replaced by

a Machine-Man endowed with her face, tempting the critics.

The inventor Rotwang, whose right hand has

forgot her cunning...

The film of all

films most admired by Ken Russell, he would screen it at every opportunity, the

structural basis on which his analysis of Women

in Love is constructed.

Mordaunt Hall of

the New York Times, “it is a technical

marvel with feet of clay, a picture as soulless as the manufactured woman of

its story.” Variety, “the weakness is the scenario by Thea von Harbou. It gives

effective chances for scenes, but it actually gets nowhere.” Evelyn Gerstein (The Nation), “Hollywood lives for money and sex. It borrows or buys its

art. It is the Germans who are the perpetual adventurers in the cinema. They

gave the camera its stripling mobility, its restless imagination. They played

with lights in the studio and achieved innumerable subtleties in the use of

black and white as a medium. Even in their scientific miniatures they have

worked with a virtuoso camera. And it was the Germans who injected fantasy into

the cinema...”

Spione

A massive Russian

spy ring uses the Haghi Bank as a front.

Blackmail,

bribery, seduction and murder are its devices.

The Secret

Service has Agent No. 326 to track it down.

Countless

observations delineate the organization and the effort to halt it.

Hitchcock is a

great admirer, the train wreck is in Secret Agent,

the finale elsewhere.

“It is

impossible to make head or tail of the story” (Mordaunt Hall, New York

Times, on the English version, Spies).

Frau im Mond

The beautiful

print issued by Transit Films and the Murnau-Stiftung

has been transferred at an incorrect speed, helping even now to grant the wish

of Variety that Woman in the Moon be shortened, howsoever.

The incalculable

indifference of critics to such a masterpiece in Lang’s best style is out

of commerce with the actual state of its influence, which is best illustrated

by the extremely circuitous manner in which Altman’s Countdown is explained

by way of Poe’s “The Gold-Bug”.

M

The version

presented in the Nineties as a restoration has a certain amount of discrepancy

in the running speeds, but only in two or three scenes.

The famous

perfection of this film is a sure sign, as in Capra, of an underlying structure

carefully prepared beforehand, allowing freedom on the set. Here, there are

almost no perturbations of the flawless surface, but they mount to the letter

“M” on the child-murderer’s coat, and give rise to a sense of

the film’s workings.

The supreme laconicism of Lang is that, as in Beyond a Reasonable

Doubt, the suspect is in fact a killer. His defense is the one offered by

Shylock, in a rather pathetic way, but he is shown no mercy by the tribunal of

criminals set up in a cellar, and none by the eventual judge before whom he is

brought by the police.

This is what

drains the mickey out of the tale, or the sense and sensibility, allowing these

compositions of perfect immediacy, the comic playing area in which actors

appear as ideal caricatures of policemen, government ministers, judges, and

their counterparts in the criminal hierarchy, and even permits a direct

parallel of the government, beleaguered by publicity, turning against the mob.

The ease of

Lang’s images, as a consequence, is almost effortless. A ball coming to a

stop, a toy balloon caught against electric wires and wafted away, the empty

place at dinner, are enough to settle the murder and cause Renoir to pan his

camera onto the empty table in La Grande Illusion, then Reed to

establish his montage in The Third Man.

But this is where

Lang is free of his rivalry with Hitchcock, at least technically. It remains to

be observed that M has the same overall form as Metropolis, two

worlds above and below with a single unifying figure, this one not a Mediator

but beyond the pale.

Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse

Mabuse’s

second avatar is Professor Baum, who runs an insane asylum and becomes

possessed by the terrible mind of his patient, as expressed in the writings

that give the film its title.

The

“dominion of crime” is Mabuse’s sole aim.

Murnau’s Nosferatu and Browning’s Dracula go into Lang’s film, a

masterwork of masterworks from which come various gags and features of The

Man Who Knew Too Much, The Ipcress

File, The Quiller Memorandum, The Drowning Pool, 2001: A

Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Family Plot, etc.

Liliom

“Oh! Ça, c’est extraordinaire!”

Life and death of

a carnival barker. The heavenly commissariat.

“Entendu, Liliom? Sur la

foire, quel silence. C’est parce qu’ils savent tous. Non, ils ne savent pas...”

A Matter of Life and Death, It’s

a Wonderful Life, Death of a Salesman,

etc.

H.T.S. of the New York Times noted “good use of

the power of illusion”.

Truffaut,

“all great films are ‘failed.’ They were called so at the time,

and some are still so labeled: Zéro de Conduite, L’Atalante,

Faust, True Heart Susie, Intolerance,

La Chienne, Metropolis, Liliom, Sunrise, Queen Kelly, Beethoven, Abraham Lincoln, La Vénus aveugle,

La Règle du jeu, Le Carrosse d’Or, I Confess, Stromboli—I cite them in no particular order and I’m

sure I’m leaving out others that are just as good. Compare these with a

lot of successful films and you will have before your eyes an example of the

perennial argument about official art.”

Fury

You can take it

as it comes (English critics have done this), or let the dead bury the dead,

but Lang wants you to know his man is guilty, as later in Beyond a

Reasonable Doubt.

Joe goes into

partnership with his two brothers rather than marry Katherine, he’s broke,

she leaves the state for a job elsewhere, it’s

the Depression. A year later, he’s arrested for kidnapping a little girl,

his gang is said to include two other men and a woman.

He escapes a

lynching by sheer luck (or what would you call it, the dynamite kills his

companionable bitch and opens the cell door), lies low and waits to see ‘em hang. Katherine finds out, but won’t marry

“a dead man”. Now he pleads “don’t leave me

alone” and stands before the judge.

This is what

makes the lynch mob so culpable, innocent or guilty the poor slob has had no

trial.

Hitchcock sets up

the identical theme at the start of Psycho.

You Only Live Once

The striking

effect achieved in the Death Row interview and noted by Truffaut is only the prelude

to a much grander surprise planned for the execution soirée at which Father

Dolan describes his understanding of rebirth. As he concludes his thought in

the warden’s residence, sirens rise all at once around the prison like a

Last Judgment, the condemned but innocent man is escaping with the help of his

former cronies.

His conversion is

amply illustrated, and Lang’s vision is really of the second death

avoided.

The European view

of Lang’s American films is just that, a crash in the Lang market can be

avoided, as with any director, by a valuation based on real assets. The

universal principle of evil seen in the two larcenous gas station attendants is

simply a commonplace of American humor, like the executive padding his expense

account.

You and Me

You get what you

pay for and, incredibly, the girl who’s been there totes it up on a

blackboard for the gang, what suckers they are (the boss is meanwhile

liquidated).

That’s the

truth of it, and with no shadow at all on their love the young couple get married in earnest, dowered with “Hour of

Ecstasy”.

Variety was flummoxed, Halliwell never took his finger

out, “curious comedy drama which never has a hope of coming off,”

to coin a phrase.

The Return of Frank James

The point of the

structure is finally to overthrow the apparatus of guilt laid on by the

railroad, and specifically to exonerate Frank James by a jury of twelve good

men and true.

Major Cobb

authors a commendatory piece for the Liberty Weekly Gazette, his first,

in the name of the people.

The charming lady

reporter from the Denver Star returns home with compliments.

Critics took

exception to this as not down and dirty enough, the triumph of democracy seemed

a good idea to Lang, dramatically speaking.

In the same

spirit, Tierney’s performance was thought to be weak.

Western Union

The North

includes the East and West, the South only the West. “No law west of

Omaha”, Moseby’s guerillas attack the

line.

The outlaw West

and the renegade South both die, wounding the East, but the Western Union is

preserved, by wish of President Lincoln in a telegram.

Man Hunt

The joke is

refined practically out of existence, it serves the

turn but leaves commentators strictly hors de combat, despite

Lang’s supervision of the exacting dialogue on a “sporting

stalk” and suchlike amusements.

Much hell has

been played with the film as a consequence by reviewers left spiteful, and

again Lang provides relief in a comic number at the Risboroughs’,

to dispel any hard feelings.

Pidgeon’s heroism, Bennett’s tenderness,

Sanders’ accuracy, and Worlock’s finer

feeling, go a long way down the track laid by Nichols & Household, there is

nothing lacking in the rendition (notable on the contrary for its bravura), yet

the power of analysis brought to bear by Lang upon his theme fairly trumps all.

An English

huntsman loads his rifle after a dry shot at Hitler on the Berchtesgaden

terrace and doesn’t squeeze the trigger, too civilized for killing anymore, “decadent” says his torturer.

He escapes

magnificently and returns to England pursued by a double, he can’t be

involved in a government incident, a confession is sought that he is an agent.

Panzers take

Poland, he’s tracked down to a cave, yes he meant it, on behalf of

Hitler’s victims, the confession is thrust in at

him to sign.

There is a girl

in it, not the treacherous violet-seller of Frau im

Mond but a London demimondaine who finds

an honest gentleman at last and not a parading butler.

He is too

fastidious, too honorable, she dies, he quells the

torturer with a silver arrow he’d given her for her hat.

Influential a

thousand ways (the subway fight is in Sargent’s

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three), marvelous beyond all description

(Bennett bouncing cheerily on Lady Risborough’s

cushioned sofa), refined beyond the critical establishment.

Hangmen Also Die!

A brutal,

distinct mark is drawn between two states of being, the hunted and the hunters,

corresponding to the two halves of the film.

A thin electric

wire of fear dominates the first. Who killed Heydrich? A surgeon in Prague, he

has nowhere to go.

Life in these

circumstances proceeds from the account given by Sternberg in Shanghai Express, one lives by faith but

one’s life hangs upon a glance, a look.

The second turns

the tables, there is a collaborator, an underground

infiltrator, a man of lofty position. He killed Heydrich, everyone will swear.

The Nazis are

left with this.

Ministry of Fear

The gift of Fritz

Lang is to bring the war home as no other.

And this with the

pure German technique that brings Dan Duryea on in a derby at the charity fete like a Berlin nightmare figure.

The Ministry of

Home Security has an advisor on Nazi psychology who is a Nazi spy.

The hero (Ray

Milland) has just been released from an asylum for the criminally insane.

And so it goes,

greatly vying with Hitchcock in a humorous way.

Londoners bed

down on the underground train platforms during another night’s air raid, one (the hero) observes how hot it is, not long before

D-Day.

The Woman in the Window

A purely surreal

representation of an amorous dream by a Gotham College professor of psychology.

It all ends

rather badly and rather well, and the lesson has been taught (murder in

self-defense, murder for gain).

Scarlet Street

An artist becomes

a great painter in New York through the intercession of a prostitute.

This is

practically Moses und Aron, a work left

unfinished because UCLA professor Schoenberg failed to get a Guggenheim

Fellowship. Kubrick, on the other hand, found in it a way of filming Lolita, and a very good way.

Cloak and Dagger

The “lever

of love”, scientists held captive by the Nazis through fear of reprisals

against relatives or civilians.

The O.S.S. sends

in a scientist to understand the dilemma. The genuine horror is manifest in the

fight scene with Mussolini’s secret policeman, which is the source of the

fight with Gromek in Hitchcock’s Torn

Curtain, a famous bow to realism.

Elsewhere in Torn

Curtain are indications of Hitchcock’s regard for Cloak and Dagger,

as also in North by Northwest.

The ground is

certainly prepared by Lang’s acknowledgment of The Man Who Knew Too

Much and The 39 Steps, also Foreign Correspondent.

It has always

stayed beyond the perception of critics (Variety, New York Times,

Halliwell’s Film Guide, Time

Out Film Guide).

Secret Beyond the Door...

Hitchcock

doesn’t haggle, Lang however drives a hard bargain with great consequences

for Huston’s Freud and Preminger’s The Man with the

Golden Arm, etc.

The constant

surrealism is on a scale with any of the avant-garde masterpieces gawked at by

juvenile film buffs who in this instance anyway slid

under the table, to read the reviews.

The heiress has a

heartsick brother safeguarding her fortune, two suitors (trombone-player and

psychoanalyst) are rejected as Mexican knife-fighters, the landed gentry has a

scion down at heels who wins her heart, she locks the door of marriage on a

duenna’s counsel, he bolts to sell his architectural magazine called APT,

his hobby is “felicitous rooms” collected at the manse.

As noted,

Bluebeard (Powell’s Herzog Blaubarts Burg,

from Bartók). There is a son by a previous marriage,

and a disfigured secretary who figures in Boorman’s The Tailor of

Panama, and a sister.

The murder rooms

are “apt”, the double room is a strange

effect that completes them all, mother and loveless wife and secretary.

House by the River

Two

houses with their riverfront gardens side by side. A man in his gazebo writing,

a woman using a hoe around a scarecrow.

The tide makes

things come and go on the river, like his returned manuscripts.

There are three

characters, the Author, the Editor, and the Hypocrite Lecteur.

The Editor is

three persons, the unseen correspondent, the downstairs maid in the upstairs

bath (due to a plumbing problem), and the author’s wife.

A purely

surrealistic formulation of the disappearing author (à la Nerval), it might have met with no favor among critics but is

one of Lang’s most electrifying works.

American Guerrilla in the Philippines

Bosley Crowther

led the critics in wishing, like Ensign Palmer, they were off to Australia, but

that is not the case, and that is enough of a film for Lang to have made

unflinchingly, or anyone.

PT men after the

fall, so They Were Expendable and Back to Bataan, but mainly Hangmen Also Die!, exiguous survival is the theme,

and then at length (Variety

complained) the possibility of resistance.

Lang’s

procedure is measured and considered in every degree, he is certain that every

joke and rag has its meaning in the context, and he even cites My Darling Clementine (Doc

Holliday’s operation).

Rancho Notorious

Rimbaud’s

tale of the Prince and the Genie is handsomely explicated in this marvelously

cool and abstruse Western. The close relation is immediately to

Hitchcock’s “Revenge” (Alfred Hitchcock Presents), and

much later to Frenzy.

Altar Keane

(Marlene Dietrich) is the “pipedream” made real before a young

man’s eyes (Arthur Kennedy) that have seen his fiancée a corpse shot

through at the assayer’s office, one bloody hand still clawed at her

attacker’s face.

The only clue is

“Chuck-a-Luck”, where Altar receives a sacrifice from desperadoes

for her hospitality.

Fantastic compression

and detail work enliven the cold, dispassionate view. The lady’s

biography is seen in flashback, riding a cowpoke over a barroom obstacle course

not shown but revealed by Lang, disputing a saloon-owner’s rules for

shilling, her defense by Frenchy Fairmont (Mel Ferrer

in powdered hair à la Ford), a polished

gunslinger. Frenchy and Altar step out from the

saloon to walk down the street, the geezer recounting this says they went to

Mexico, she hikes her skirts to cross a puddle, they

pass a cantina and reach her digs.

Milestone’s

A Walk in the Sun has the precedence of ballad form (Fuller’s

critique is perhaps absolved).

Clash By Night

The most natural

and detailed settings are constantly established to let the unreality shear off

in subtle and spectacular ways, mirrored in the Doyle house smartened up by May

on her return.

The fishermen

have a regular audience of gulls and seals clamoring for a scrap from the

catch, so too the projectionist and the politician in lives divorced from

reality feast on the scattered morsel.

The roots of

Fascism, says Odets, a lost calling for some sort of “authority”.

Still more the

evident symbolism of Uncle maintained until May’s arrival, and then the

idle dementia of Pop before the wedding and his threefold blessing,

“fish, wine, and love, for everybody.”

Lang precisely

defines the subtlety of the horizon line mainly with his screenwriter, Alfred

Hayes, in dialogue given to Earl and the two women.

The Blue Gardenia

A superb noir Blackmail,

even to the phone booth, featuring Nat “King” Cole in a nightclub

scene performing the Lester/Lee title song (arr. Nelson Riddle) at the piano.

The Big Heat

Duncan’s

suicide and note, and Mrs. Duncan’s appropriation of the latter, look

like a reflection of the main gag in Tay Garnett’s Cause for Alarm!

“Politicians”

sit at Vince Stone’s card table (they include a city councilman and

Police Commissioner Higgins).

The style at the

outset is rather close to Perry Mason, as seen on TV.

Bannion questions Mrs. Duncan, and you see the beauty of a

cop’s mind as it clicks over, sifting evidence and knowability,

probability and certitude.

Half the time,

Lang cuts in the camera, giving you the tour of every scene.

At home, Bannion’s in his castle. When the phone rings, he gives

it a dirty look.

Lucy Chapman is

tortured and killed. At the police station, Bannion

is seen walking by a poster that reads, “GIVE BLOOD NOW”. The scene

in Lieutenant Wilks’ office introduces a

background complexity with consequences for Kubrick’s 2001: A Space

Odyssey.

The real magic

takes place back at the Bannion household. His little

daughter wants him to help her “build a police station,” his wife

wants him to shower and make cocktails. He knows the department is corrupt.

Lang has spent considerable time laying a psychological foundation. Bannion places another toy brick on the

“station” and it collapses.

The department

watches over Mike Lagana, Vince Stone’s boss.

Lang hired a well-known actress to sit for her portrait as Lagana’s

mother—only the portrait appears in the film, not the actress.

Lagana’s home is a remarkable scene, with his

daughter’s jitterbug party in the background. It’s his castle.

“Too elegant, too respectable.”

“I’ve

been thinking about Lt. Wilks,” says Mrs. Bannion. Her husband replies, “that leaning tower of

jelly?” She continues, “you attack yourself from all sides like

Jersey mosquitoes.” A track-and-pan expresses Bannion’s

joy in his daughter, and Lang’s in his technique.

Mrs. Bannion goes for the babysitter and is blown up. Bannion sniffs out the Commissioner and is suspended. His

badge is revoked, but his gun he “bought and paid for” himself.

He’s

“had a bellyful of the department.” When a crony says, “no

man’s an island,” Bannion tells him to

get out.

Vince Stone,

“some career, huh? Six days a week she shops. On the seventh, she

rests.”

His moll jokes

that her perfume “attracts mosquitoes and repels men.”

Lagana’s daughter, her coming-out, etc., unseen like any

other such character in Gogol.

Mike Lagana, “prisons are bulging with dummies who wonder

how they got there.”

Headlines

threaten the election. Things are changing. A grand jury means deportation. Lagana doesn’t want to end up “in the same

ditch with the Lucky Lucianos.”

Bannion attempts to question the “scared

rabbits.” He takes Vince Stone’s moll to his own hotel room, from

Vince’s club “The Retreat” on Club Row. She tells Bannion, “you’ll never get anywhere in this

town by not liking Vince.” This is the central moment of the film, she

makes overtures to Bannion, and he backs to the wall

beside a light fixture (on).

She’s

disfigured by Vince. The Commissioner has to quiet the doctor.

“I’ll try,” he says, “I’ll try.”

Back in Bannion’s hotel room, the light fixture is off, but

you see Bannion and the moll (her face bandaged) and

between them in the background a lamp emitting two cones of light upward

and downward.

Bannion, “our city is being strangled by a gang of

thieves, and you protect Lagana and Stone for the

sake of a soft, plush life.”

Mrs. Duncan is

making a living by not revealing her conscience-stricken husband’s

suicide note. With her dead, “the big heat falls for Lagana,

for Stone, for all the rest of the lice.”

At this point,

you notice the really complicated designs Lang has worked up, and the

strenuous, forceful acting required of his players.

Only

ex-GI’s are capable of withstanding Lagana’s

forces, and only with the keenest foxhole awareness.

The moll kills

Mrs. Duncan. In Vince’s apartment, during the confrontations and

shootouts, you finally see what Lang is after. In Scarlet Street he

invented the 1940’s. Here, he achieves the vertical geometry of the

1950’s, and looks ahead to the 1960’s (there are some details here

precisely recalling the décor of Scarlet Street, for perspective).

Dying, the moll

inquires after details of Mrs. Bannion’s

character.

“LAGANA,

HIGGINS INDICTED!” reads the newspaper headline. And once more for the

audience, the poster, “GIVE BLOOD NOW”.

The absolute zero

at the centerpoint is really as mild as Frost’s

“word I had no one left but God.” There are other dimensions in

Lang’s work, but it is absolute zero nonetheless.

Human Desire

The pure Lang

distillate of madness and impossibility, to which Crowther of the New York

Times said, “so what?”

Because it all

comes to nothing, which is what Crowther observed. He should have stood in bed.

A marvelously

clever woman (Gloria Grahame) leads her fink (Broderick Crawford) by his chain,

their monkeyshines take in a Korean War veteran (Glenn Ford) who drives a

train.

Lang’s

train-rides through the opening credits and the film are immensely enjoyable.

The engineer has seen enough killing to know a gratuitous venture, and bows

out.

It’s all so

very mysterious, for film critics, that they simply evaporate (Variety’s,

for example).

Meanwhile Lang,

with Amfitheatrof’s clever help, puts together

a dissolving conundrum on the basis of Zola and Renoir, justly admirable, and

with such a cast.

Moonfleet

Lang’s

magical epic looks at Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn from a standpoint

beyond Secret Beyond the Door to restore the fortunes of a ruined house

in eighty-five minutes of CinemaScope and Technicolor, with a memorable theme

by Miklos Rozsa on the

crashing surf of Dorsetshire or Southern California,

filmed behind the opening credits.

John Mohune goes to Moonfleet with a note for Jeremy Fox,

captain of a band of smugglers. The lad is a descendent of Sir John Mohune, who “sold his honour

for a diamond”, and whose knightly ghost is said to haunt the churchyard

murderously. Lang has a picture of the scene, a low building with a light by

the door amid the gloom of the clouded heath, beside gravestones and the statue

of an angel with staring eyes romantically stylized like the other statue of

Sir John with his sword dominating the interior of the church from the back,

while the minister sermonizes against the credulous fear of Redbeard,

as the ghost is called amongst the villagers.

Young John Mohune in the shadow of the angel stumbles into the

underground crypt used by smugglers to bring brandy and silk from the sea, and

breaks open Sir John’s coffin by innocent misadventure, discovering a

silver locket that later proves to bear the secret of the hidden diamond, a

cipher of misnumbered Bible verses written on

parchment.

Fox needs the

diamond for his partnership with Lord Ashwood, who

wants to finance a mission of piracy against enemy ships (Lady Ashwood is Fox’s mistress). Despite the protection of

Lord Ashwood, the army presses hard on Fox’s

smuggling operation, and he has but the one chance to make good his losses.

Nevertheless, he abandons the venture out of tender feeling, though Lord Ashwood stabs him in the back for it and receives a bullet

himself. Wounded by Ashwood and sought by the army,

Fox returns the diamond to its rightful inheritor and makes his way to the sea.

The

cinematography recalls the burnished oaken color of Huston’s Moby Dick

the year before. The ladies’ costumes in particular are fetching and

scenic. Variety noted a passing resemblance to Treasure Island,

but not to Great Expectations. Moonfleet has in turn had

considerable influence, most recently on Polanski’s Oliver Twist. Rozsa’s contribution to scenes like the descent into

the well is noteworthy. A fight between Fox and one of his men at The Halberd has

Fox draw a rapier and the other take the inn’s namesake down from the

great chimneypiece.

Halliwell’s

Film Guide found this all rather

boring, a view anticipated by Lang in the boy’s nap during the final

action. Godard did not see this film in France until 1960, and placed it among

the ten best films released that year (with Chabrol’s Les Bonnes femmes, Nicholas Ray’s The Savage

Innocents, Donen’s Give a Girl a Break, Mizoguchi’s

Sansho Dayu,

Buñuel’s Nazarin, Dovzhenko’s

Poem of the Sea, Hitchcock’s Psycho, Cocteau’s Le

Testament d’Orphée and Truffaut’s Tirez

sur le pianiste).

While the City Sleeps

The grand

symphonic treatment of all Lang’s themes owes its title to the quotidian

surrealism of a daily newspaper. No critic has recognized the Kyne symbol as that of Citizen Kane, the news story

covered here is the one first proposed by Charles Foster Kane as he began his

tenure at the Inquirer (“woman missing in Brooklyn”).

Still another

working theme appears to come from Wise’s Executive Suite, Lang of all people knew a good

film when he saw it. The three top executives assigned to crack the case are

more or less manifestly unworthy, yet the managing editor of Kyne’s newspaper, the Sentinel, has the good

sense to do his job and rely on his top crime reporter, who has a Pulitzer

Prize and nowadays writes books (the other two run the Kyne

News Service and Kyne Pix), furthermore he does a

twice-nightly commentary for the Kyne TV arm.

Kyne Pix is conducting an affair with Kyne, Jr.’s wife (the

playboy scion has just inherited, the three-way hunt is his

“gimmick”), Kyne Wire is negotiating a

lucrative Midwest television deal. The reporter’s fiancée lives across a

corridor from the love nest.

The murderer is a

“mama’s boy” characterized in one shot (spying from a

bookstore entrance) and his costume as the young killer in The Big Sleep,

and looking directly ahead to The Boston Strangler.

The subway fight

in Man Hunt is resumed and elevated to a position from He Walked by

Night or The Third Man, the genuine liberality of Lang’s

resources springs from an extraordinarily pliant technique with a plethora of

thematic considerations, and ends every bit as happy as Wise.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

The trick

resemblance is, ultimately, to An American Tragedy or A Place in the

Sun, but the real structure is elucidated by Hitchcock in Psycho.

For this is the

tale of a man who postpones his wedding to write a book, a second book, mind

you, his editor demands.

Then

there’s the body, and a convenient alibi, set up to prove the weakness of

the courts.

Bosley Crowther

lectured his New York Times readership on the law like a judge, bless you, instructing a jury, “it

wouldn’t stand up in court.”

Variety lost the opening thread and never recouped,

“the melodrama never really jells.”

Halliwell was at

his most petulant, “the distinguished director is at his most

flatulent.”

Dave Kehr in the Chicago Reader has a “shatteringly

nihilistic conclusion.”

There is a

monumental analysis by John Huston in The Mackintosh Man, from Across

the Pacific.

Der Tiger von Eschnapur

Lang’s

supreme utterance on the Hitler nightmare, at one remove (Joe May) for

prophylaxis.

Debra Paget as

the half-Indian temple dancer, Paul Hubschmid as the

Canadian architect in a backward province of the sub-continent.

The flavor of the

serials, deliberately maintained.

Das indische Grabmal

The continuation

and conclusion of Der Tiger von Eschnapur.

The architect and

the dancer are recaptured, the Maharajah announces his

own impending marriage and her doom.

Eugene Archer saw

the compendium, Journey to the Lost City, and ridiculed it in the New

York Times, having no idea what it was all about, none whatsoever.

There is a

characteristic diffidence in the filming, an alternating distance and interest,

Lang films from across the room or builds up Indian miniatures, or something

else again.

Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse

The thousand eyes

of Dr. Mabuse’s latest avatar are television cameras in every part of the

Luxor Hotel. From a control room in the basement, formerly a listening room

when the Nazis built the hotel in 1944, and now updated, every manner of

meeting and conversation can be observed (the Nazi idea had been to group these

hotels together for ease of surveillance). Lang’s camera lingers on a

monitor, after pulling out from the shot onscreen to show that it is one.

There are more

red herrings, flat contradictions, twists and turns than can be ascribed to

anything but an effect of style. Nothing is what it seems, except Inspector Kras, and he’s nearly killed twice.

Dr. Mabuse is

supposed to have died in 1932. The woman on the ledge at the Luxor, coaxed in

by an American whose name isn’t Taylor but Travers, the insurance agent

Hieronymus B. Mistelzweig (“B stands for

belly”), even the hotel staff are all suspect.

The relation to

Hitchcock is supplied by a two-way mirror in one of the rooms, and a wife with

a secret identity, so Rear Window and Vertigo are pointed out.

The Bond films are prefigured as well. The ultimate aim of Mabuse as ever is

“to throw the world into chaos, and be the only man able to profit by

it.”

The particular

plan is to hypnotize a woman into embroiling an American multi-millionaire into

marriage, after which he dies leaving all to his wife, especially the nuclear

plant and the missile works. “The celebrated button” is waiting to

be pushed.

This is Lang, the

greatest man in any cinema among his equals, lifting Germany’s head a

little after the nightmare. He reserves until the last shot (answered by

Russell in Aria) a sense of loss, with reference to Dreyer’s Ordet.

Mainly there is

Inspector Kras, an island of sense in the turbid seas

all around him. “Interesting” is his comment on the various clues

he’s offered.

Lang has a trick

in the first half of initiating a new setup amidst a conversation, like a new

idea, which strongly resembles the rocking-chair scene in Huston’s The

Maltese Falcon (his other trick is in the car chase, a plain treatment

preparing a vile deed). He has the best actors in these roles, Fröbe, Preiss, Van Eyck, Addams, Peters. The technique is

refined well beyond the elegant.