The

Mad Miss Manton

The Mad Miss

Manton resembles the screwball in

type throughout the first scene or two. It’s three a.m. in New York, Melsa Manton walks a batch of dogs past the doorman of

her apartment building into the street. One of the dogs hurts its paw on the

debris of a subway under construction. Melsa commiserates, saying it

doesn’t seem fair that the poor creature should suffer the inconvenience

and then be barred from riding the subway when it’s finished. The streets

are deserted, yet a man wearing evening clothes emerges from a house and drives

away hastily. “Ronnie,” she calls to him in vain. She can’t

resist entering the door left open behind him, the house is dark, she uses her cigarette

lighter to examine the interior, an older man lies

dead on the hearth, shot through the temple. She runs out, shedding her cloak,

to call the police. Her garment now consists of a short white frilly dress with

a bow, something like Little Bo-Peep, Baby Snooks or Shirley Temple. She has

come from a costume party, an artists’ ball, where she had to resist a

man’s advances, he’s dead, not the same man, etc. The police find

no body, at the station her identity is discovered.

Miss Manton and her friends once stole a traffic light in a scavenger hunt for

charity, their pranks are notable, the lieutenant

sends her home. The deep New York ennui of Sam Levene as the lieutenant is the

proper screwball response, but the oddities of the scene propel the film into

another type as the model of Roy Del Ruth’s Topper Returns, and

this is only the prologue.

Melsa’s

adventure, the madcap foolery of a wealthy debutante, appears in the newspaper

with a photograph of her, next to an article headlined, “BANKERS URGED TO

SEE SELVES AS PUBLIC SEES THEM”. Melsa goes to see the editor in his

office, and finds a reporter given additional duties for the same pay, who is

presently expounding on sharp business practices. “Wall Street has hit a

new low,” he says, forming an editorial. The scene is practically

repeated in Polanski’s Chinatown, her process server hands him a

summons, she is determined to prove her case in court

with a libel suit for one million dollars. Isn’t she afraid, the editor

asks, of paying a higher tax rate? She’ll give it to charity, she says,

there was a body in that house.

Melsa and her

debutante friends gather in her apartment to decide on a course of action, a

knock on the door is her cloak and a knife with a warning note. The editor

shows up, belittling her endeavors, the girls beset him, leave him bound and

gagged, and press on to Ronnie’s apartment. Nothing’s amiss there, one of the girls dawdles to make a sandwich. Ronnie

is in the refrigerator. The lieutenant hangs up on Melsa, and so the bedraggled

editor gets the news from his own paper on the street, “FROZEN PLAYBOY

MYSTERIOUSLY DEPOSITED IN NEWSPAPER OFFICE”.

A jeweled brooch

at the scene of the earlier crime had turned up in Ronnie’s apartment,

evidently by way of Melsa’s cloak.

Ronnie’s

affair with Mrs. Lane, wife of the first victim, led to his murder. Lane had

been blackmailed by his partner in the firm of Lane & Thomas, Brokers,

because Mrs. Lane was formerly Mrs. Norris, the wife of a gangster. Norris has

been released from prison and become a foreman on the subway construction. He

was at a hockey game in Madison Square Garden when Lane was killed.

Melsa tries the

experiment, ten minutes is not enough time to get from the Garden to the murder

scene. “NORRIS ALIBI SUBSTANTIATED”, followed by a report of new

evidence from Melsa with a secondary article conveying, as always in this film,

the real tenor of events, “MOVE TO BAN OFFICE MERGERS”.

Melsa and the

editor, who is quite smitten, are set as bait at the Las Pampas Club, a swank

spot where the waiter is an undercover cop and smiling Sgt. Sullivan is in the

orchestra with a Tommy gun at the ready. A pistol peeps through curtains, their

champagne bottle gets it. A bit of tar paper is the only clue. Melsa remembers

the construction site.

Down in the

tunnel, the shadow of a gunman looms. It’s the night watchman holding his

pipe. The electric cart on the track zips along quite fast. She gives him a

tip, “buy yourself a pipe that looks less like a

gun.”

Norris was

jealous, thought Lane beat the wife, hated Ronnie, got

a great deal of pleasure from killing, at first.

Hollywood

lighting is used to advantage, the jokes are plentiful. Stanwyck and Fonda are

unjustly compared with the altogether different roles in Preston Sturges’

The Lady Eve. Hattie McDaniel is in rare form as the scowling maid who

refers to the debutantes as “that mob” and tells a telephone

operator in true New York abstraction, “I don’t know no numbers

‘cept policy numbers.”

Carolina

Blues

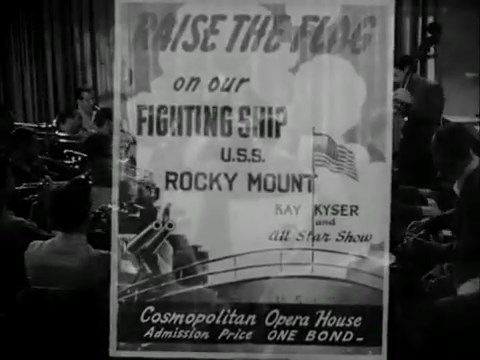

The essential genius of Kay Kyser, years on

tour, weeks piled up entertaining the troops, home for a brief vacation but

pressed into service instead for a defense plant gig, bond night at the

Cosmopolitan, the wartime whirligig exhausting the band.

He is more than calm at the center of the storm, but the Bradford

millionaire isn’t all he’s cracked up to be and has a

dancing daughter.

Before Robert Hamer’s Kind Hearts and

Coronets, Victor Moore as the Carver family. Ann Miller, music from

top to toe. Jeff Donnell as the publicity gal mad for Ish Kabibble. Georgia Carroll, who has a way with a song. Harlem steppers, Broadway shleppers, with

the sublime songsters and Jason’s typically original idea of a musical

that fits all these circumstances, a very vivid dream. “Hello,

yes, this is Kay Kyser. Oh, I’m sorry, um,

who wants to speak with me? The mayor! Well, lift him up to the

phone!”

“Will you stop worryin’?

You’re makin’ me noivous.

Kibitzer!” Question of a destroyer from his N.C.

home town, the band plays pickup in a scene rivaling George Marshall’s “A

Knife, a Fork and a Spoon” number in Pot o’ Gold with Horace

Heidt and His Musical Knights.

A song of the rivers, “that sounds like a music cue.”

Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times, “it is likely to leave you depressed.” TV Guide,

“decent”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “wispy comedy musical”.

Okinawa

An oblique view of the battle from a forward gun mount on a destroyer,

a complicated sequence of mainly conversational metaphors (cf. Coward

& Lean’s In Which We Serve and Milestone’s A Walk in

the Sun) that fortuitously drops the gloves before the “kamekatzes’” penultimate attack and throws in

one of the occupied for good measure.

Therefore

an extraordinary undertaking, a view also from the bridge, noted by Robert

Montgomery in The Gallant Hours.

“I’ve

gargled more salt water than you ever sailed on!”

The Secretary of

the Navy looks on many a scene from his official photograph.

Tropical Fever: Its Cause and Treatment (cf.

Henry King’s Marie Galante).

Death of FDR,

“one of the best friends I had.”

The “divine

wind” blows.

H.H.T. of the New York Times dutifully went for

“dull glimpses... wartime dogmeat... a tired

old rubber band... clichés... hand-me-down colloquialism... the most dismal war

offering so far this year... marking time in Hollywood’s Siberia,”

that is all.

The ships of the

line on picket around the home island all have code names from the funny papers, this one is “Blondie”.