Dangerous

The

volatility of genius is made into a study, the stage actress who invents

everything immediately gets compared with the society architect and his estate

plans in escrow. “Poetry”, said René Char, “is the side of man

refractory to calculated projects.”

She

is “mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” failure is her world,

fortunes have been lost, a leading man has died, no producer will hire her. The

real and its counterpoison are further analyzed as the grass widow and the

bookkeeper who won’t divorce her. He is now an employee of his own firm.

A

suicide pact is formed in a speeding car, she smashes them into a tree, let one

live or die, free or annihilated. She recovers, he’s badly hurt.

The

opening of a new play financed by the architect at considerable risk to his

fame and fortune is canceled, she hears the rebuke. There is no jinx,

it’s time to pay her debts. The play is rescheduled, the insufferable

husband, a bandaged milksop, sees from his hospital window the wife ascend the

steps outside, a bouquet of flowers in her arm.

The

major theme of ennui introduces the picture with Mr. Farnsworth at his club

fortifying himself against Mrs. Farnsworth’s dull dinner guests. At the

party, rich young folks (architect, sweetheart, and polo-playing chum) slip

away to sideshow amusements. In a low dive where they do not stay to drink, the

architect lingers to address the gin-swilling actress who inspired him to art.

He marries his high school sweetheart after all is said and done, and resumes

his practice.

The

trailer almost suggests a taming of the hellcat with Franchot Tone and Bette

Davis. The critics saw a tedious melodrama. Green, Haller and Orry-Kelly in

concert with the actors have put together a masterpiece of constant fascination

by creating a space in which Laird Doyle’s script operates to the last

degree of efficiency and expression. Genius is practically defined as an

element visible onscreen (Haller’s cinematography is one invention after

another), its bearer gathers herself to “climb the bitter steps”

rather than fly apart into a zillion quarks.

Davis

received an Oscar for her brilliance, modestly praised Katharine Hepburn, and

deserved it for her heroism. As so often in her career, the film was not

understood but Variety and the New York Times held the general

opinion that she carried it well.

The Gracie Allen Murder Case

The

millwheel of justice slowly grinds out “The Buzzard”, but when

Philo Vance takes the case, exceedingly fine.

A

study of nonplussedness, with Kent Taylor in the

George Burns role, the diapason of ecstasy is reached when Warren William walks

into it, “obviously the witness is in a perpetual state of confusion.”

“Oh,

thank you, Fido.” The title

character on her own is so formidable, she frightens herself.

The

mob eats its own, to spare the wealth. “Irrefragable judgement,”

says Fido.

The

two bodyguards are cited in Whorf’s Champagne

for Caesar, their dance with Vance’s new “silent partner”

is a thing of grrreat beauty.

“One

of the blackest” of the black arts, Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times called the cinema, on the

same day pronouncing against the star and this picture, “probably just

about what you think.”

Leonard

Maltin, “fitfully amusing”.

TV Guide, “silly but fun”.

Dave

Kehr (Chicago

Reader) notes the director is “underrated”.

Halliwell’s Film Guide is unimpressed, but cites Variety memorably, “smacko for

general audiences... one of the top comedies of the season.”

The Fabulous Dorseys

This

is intriguingly constructed in several ways. First, it’s a terrifically

funny, easy, entertaining film, which saves its note of tragedy for a

modulation at the end. At the same time, it borrows a MacGuffin from Reisner’s The

Big Store to make the love and musical side interest a functional

part of the film itself. The three units (Arthur Shields/Sara Allgood, William

Lundigan/Janet Blair, Tommy & Jimmy Dorsey) are kept in constant play. The

model is Laurel and Hardy, and the set pieces (dance hall, jazz club,

“Green Eyes”) are complete in themselves. The silent movie theater

scene is a masterpiece in its own right, probably remembered by Russell in Song of Summer.

Paul

Whiteman, Art Tatum, Ziggy Elman, Bob Eberly, Helen

O’Connell—it’s one of the most musically aware films from

Hollywood, from a thoroughly professional perspective. It’s the original

of Davies’ The Benny Goodman Story,

an inspiration (the opening shot’s here, for example) of Scorsese’s New

York, New York, and maybe is recalled in Malle’s Au Revoir les enfants.

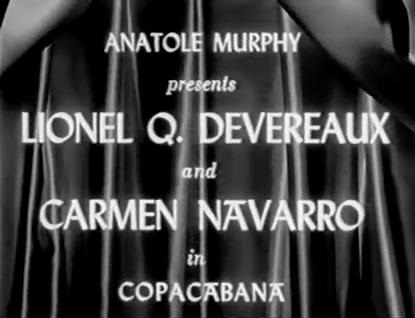

Copacabana

A new act for the Copa,

where the girls on the floor wait for “Leo McCarey and the rest” to

adore them, a brilliant idea.

“The

most untalented man I’ve ever seen.” Devereaux and Navarro, strictly

from hunger pangs.

Mlle. Fifi and agent and

Navarro. “Say, for a man

with no education you’ve done all right.” Carmen Miranda, a

continent in the Southern Hemisphere, a very able comedienne, a fine chanteuse.

A

rival agent brimming with clientele, “this guy must handle a flea

circus.” A night at the celebrated nightspot, a fact much complained of

in Crowther’s hand-me-down review, silly ass,

Abel Green is there, Louis Sobol and Earl Wilson,

too.

A

sublime film, Groucho Marx ringmaster, a little New York glamor and

sophistication, with Andy Russell, Steve Cochran, Gloria Jean (a notable

daydream sequence begins with a dolly-in to her mind) et al. “Envy him,” says Stoppard, “his twofold

security.”

Anatole

Murphy, the Hollywood producer. “Well, if it isn’t Mr. Liggett, almost the biggest agent in town.”

“You’re

the first star in the history of show business who’s ever said a nice

thing about another star.”

“You’re

lookin’ at the smartest agent in this whole town, I just pulled the deal o’ the century.”

You can ride a bucking bronco or a pony, you can cut a calf in half and make baloney.

“Oh,

come on honey, spit it out, womens

to womens, uh?”

“Mademoiselle

Fifi is now floating down the East River, including

her veil and the whole outfit.”

“The

last address I had for her was at the Casbah,” ŕ la Boyer.

Green’s

study of Marshall’s The Goldwyn

Follies is a natural, it winged past the critics with amazing speed and

legerity, leaving them covered in fairy dust all over.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “hand-me-down

musical frolic.” Leonard Maltin, “unengrossing musical comedy.” TV Guide, “silly farce”.

Billy Mowbray (Film4),

“uninspired

direction of a lacklustre script”.

Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “lame musical comedy”. Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“thinly produced comedy”.

Invasion

USA

“The

People’s Government of America will take the wealth from the greedy, the

speculators, and the capitalistic bourgeoisie, and distribute it among the

workers, whose labor will never again be exploited for the benefit of the

warmongers of Wall Street.”

A

very precise forecast, down from Alaska to Puget Sound, Oregon and California,

which burns like Napoleon’s Moscow. Boulder Dam is bombed, a defense is

made at Washington, D.C., but New York falls...

Homage to Orson Welles (the Mercury Theatre

broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of

the Worlds).

“Tomorrow

springs from today, like—like water from a rock.”

O.A.G. of the New

York Times, “it is a ‘message’ picture.” TV Guide,

“interesting piece... still offers a provocative message.” Mark

Deming (Rovi), “spectacularly paranoid”. Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“ludicrous, dangerous, hilarious”.

Top Banana

What

the title signifies in burlesque terms, a great work of art devoted to its

subject, “what the hey!”

This

naturally is one of the works that Friedkin has to draw on for The Night

They Raided Minsky’s.

The

critical response may no doubt be understood in view of precious snobbism on

the part of reviewers.