Dr. Who and the Daleks

Dr. Who’s time machine (TARDIS, Time and Relative

Dimension in Space) looks like a police box because the police have seen it

all.

By fortuitous

engagement it takes the doctor and his little family to a catastrophe worth looking

into.

Subotsky, Flemyng, a great joke to open the proceedings,

not too far from Juran’s First Men

in the Moon.

“After the

final war,” mutations in a world of ash, question of radiation sickness

and immunity thereto. The Daleks live in self-propelled metal suits like rather

flash dustbins, as has been observed. The Thals are

quite like Shakespeare’s fairies, they have a drug that protects them.

City and

countryside are a great divide.

Creepy creatures,

the Daleks, with comical electronic voices like great bleating Wizards of Oz,

treacherous too and murderous. Natch, it’s the Thals’ drug they want, to leave the city and conquer.

Wonderfully

filmed in Technicolor and Techniscope (George Pal’s The Time Machine is of course the model).

Variety

was not averse but not wowed, either.

Tom Milne (Time Out) says “plodding...

shopworn... moderately imaginative... tacky... tackier...”

According to Film4 the Daleks are

“classy” and there is a “rather weak script”.

TV Guide

describes Dr. Who as “a time lord”.

The

neutronic bomb and the deadly swamp.

Mike Hodges has

it in mind for Flash Gordon, and, who

knows, Ken Russell perhaps remembers the “final battle” scene

(“destroy the Thals!”) in Billion Dollar Brain.

A great actor

bears this on his shoulders, supported in every department.

“Skipping

the gorge” is from North West

Frontier (dir. J. Lee Thompson), the mirrors from Solomon and Sheba (dir. King Vidor).

Kubrick has the

array of monitors in the city for 2001: A

Space Odyssey.

The countdown is

from Hamilton’s Goldfinger, of

course, the Daleks’ camera eye from Haskin’s The War of the Worlds.

A memory of the

Roman conquest, goes the punchline.

Daleks’

Invasion Earth

2150 A.D.

Smash-and-grab,

time out of mind. The ruins of London, falling down. “It’s all

different,” exclaims the abstracted copper. A flying

saucer not unlike the Albert Hall.

The

Robomen.

“Very advanced,” Dr. Who observes, “miniature antennæ!” Wary human survivors,

furtive. “Obey motorised dustbins?

We’ll see about that!”

Dr. Who is very

nearly “robotised”. J. Lee Thompson takes

up the note in Conquest of the Planet of

the Apes and Battle for the Planet of

the Apes, demonstrably from Cartier’s 1984.

Flemyng exerts

himself to appreciate the comic possibilities of the Robomen,

automatons. How like Juran’s Selenites are the

Daleks, in a hard insect way. Resistance is all but futile. Little Russian

dolls with a plan to gut the Earth and occupy it elsewhere.

The question, as

any fool can see, is what is to be done? The

poetry of Earth is never dead, Dr. Who has seen the Daleks destroyed, some

other time, some other place, before or since. The invasion is definitively

quelled.

Robert Wise

doubtless remembers the copper’s climb in The Andromeda Strain.

Variety,

“it is all fairly naive stuff decked out with impressive scientific

jargon.” Hal Erickson (All Movie

Guide), “entertaining”. “Limply put together,” said

Halliwell’s Film Guide of the

first film, “and only for indulgent children,” in that Dalek voice,

of the second “a sequel, no better.”

The Split

Flemyng’s

great work pivots on its last few frames, a rare effect in films but not

unheard-of (Cornfield’s The Night

of the Following Day, Malle’s Crackers).

It is something

of a departure, as film critics say, and not so.

A caper film, to

employ another “term of art”, one admired for its facility by Renata Adler of the New

York Times, who, like Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, saw primarily a racial angle.

It’s a

question, for Samuel Beckett, of the “rupture”. Thornton

Wilder’s view of this has been filmed by Rowland V. Lee and Robert

Mulligan.

“Lacking in

real flair... a pleasing, if undemanding modern noir thriller” (Time Out Film Guide).

“Busy,

brutal”, says Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “totally unsympathetic.”

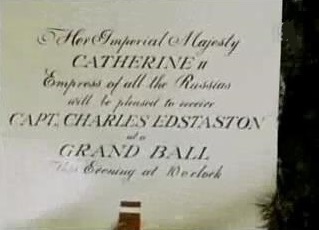

BERNARD

SHAW’S

Great Catherine

“Whom Glory still Adores”

Contemporary

views, then Morris et al. As Franklin in London, Capt. Edstaston

at St. Petersburg. Reflexive things having to do with Lean’s Doctor Zhivago are overborne by the

inculcation of Pichel & Holden’s She

and the foreshadowing of Fellini’s

Casanova, gentleman among “pigs!” The Empress of all the Russias speaks German familiarly, the captain of dragoons

carries a brace of small pistols, his word is “stand off!” A role

for O’Toole somewhat after the lines of The Day They Robbed the Bank of England (dir. John Guillermin), if

you like, he presents a glacial deadpan to Mostel’s

Potemkin, anciently derived in effect from The Lady Eve (dir. Preston Sturges), no

doubt. The sublime levée concludes

the first skirmish, “sometimes a person has to go a very long distance

out of his way to come back a short

distance correctly,” the

second represents the Battle of Bunker Hill in miniature (cf. Hamilton’s The

Devil’s Disciple), “you sank my ship!

That’s against the rules.” A certain stylistic flair corresponding

to Zeffirelli’s concurrent The Taming of the Shrew will be noted.

Howard Thompson

of the New York Times was for a jig

or a tale of bawdry, “Mostel is overpowering...

the rest

of the picture pales and teeters uncertainly.” Variety, “atmosphere it has.” TV Guide, “what a mishmash!” Hal Erickson (Rovi) looks

down his nose, “Shavian wit is given short shrift”, shrift look

you, “in favor of 2-reeler slapstick.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “chaos”, citing Michael

Biullington in the Illiustrated London

News, “padded out”.

Ken Russell’s Russian dancers (Isadora

Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World) appear for the second time

that year, after The Party (dir.

Blake Edwards), to initiate the final skirmish at the Grand Ball, another

Gulliver, “I am—ticklish, Ma’am.”

The Last Grenade

A curious

circumstance, prefiguring Coppola’s Apocalypse

Now and reflected in “The Year of the Horse” (dir. Don Weis for

Hawaii Five-O), an American yo-yo on

his lonesome in the Far East making border trouble.

This is very much

the raison d’être of

Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May

(cf. Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite).

Naturally, the

British colleague lately victimized goes in after him (cf. Kubrick’s Dr.

Strangelove).

Flemyng is a poet

in England and China of the great city and, by contrast, where the rubber meets

the road, so to speak.

The helicopter

gunner of Kubrick’s Full Metal

Jacket is in evidence from the outset.

Dankworth on

Holst, Hume cinematography, Stanley Baker, Alex Cord as the loon, Attenborough,

Blackman, Keir, Glover, Thaw, Johnson, Sim et al.

The Catholic News

Service Media Review Office says, “doesn’t make much sense and the

movie is a dud.” TV

Guide, “flat... predictable... unrealistic”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “few

redeeming qualities.”

Harry

and Kate at the Emperor’s Paradise. “Here and there, Malaya, Korea... I’m not as good looking

as King Kong or as funny as Frankenstein.”

“Oh, I

don’t know.”

The same

conclusion is reached in Donen’s Saturn

3.