A

tale of two cities, Every Nite at Seven in New York, Every Night at Seven in London.

Bosley

Crowther of the New

York Times, “the best that we can say is that it has one swell number

in it.” Variety,

“two of the numbers are sock enough to almost carry the picture by themselves.” Leonard Maltin, “pleasant”. Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “doesn't cohere quite as well as his best work.” Geoff Andrew (Time Out), “lively Technicolor musical”. TV Guide, “a

lovely bit of frou-frou.” Hal Erickson (Rovi),

“brilliance and virtuosity.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide says “journalists congregate... thin musical...”

Andrew Sarris (The American Cinema), “intermittent

flashes of inspiration.”

Love Is Better Than Ever

Echt New York, Broadway.

“See?

That’s why I turned agent, no straight men left.”

Case of the

academics, a dance teacher wants to buy a routine from two clients, male twins,

in New Haven (cp. Footlight Parade,

dir. Lloyd Bacon). Seaton has Teacher’s

Pet for this, and how (Altman has the negotiating agent in McCabe & Mrs. Miller).

“If

there’s anything I like, it’s a gal with a mother in Texas” (cf. Sidney’s Anchors Aweigh).

The class of

Terpsichorean toddlers is one of the very most sublime jokes in Donen’s

bundle, and his ease with a joke is remarkable, Kathleen Freeman as the costume

lady uses a pincushion on her wrist like Lionel Atwill

at his darts in Son of Frankenstein

(dir. Rowland V, Lee) quick as a wink. “I’m here for the American

Dancing Instructors of America convention.”

“I’ll

keep your secret.”

Stevens’ Woman of the Year is very nicely

adumbrated.

“Everybody

goes to 21, you gonna be different, you gonna start a whole new world?” Just like home, 21

is, Gene Kelly eats there, and the Copacabana is right out of Singin’ in the Rain, most amusing (cf. Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success), “because,

you see, although we’re glamorous and beau-teeful,

we’re just intelligent girls at heart.”

Donen proved

here, as later in Surprise Package,

too fast for critics to follow, and a good deal ahead of his time, thus Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times, “foolish little fable... watery nonsense...

insufferable... we regret the necessity to note that it manifests no

improvement in either movies or love,” get him, will you? Necessity!

Strictly from famine, the B.C. “we”! “Movies or love,”

he says, “M-G-M made this picture, and we regret” etc. “But

heaven deliver the heedless...” (it opened

“at

the Trans-Lux Fifty-second Street Theatre”,

see Mackendrick). Leonard Maltin, “forgettable

froth”. TV Guide,

“lighthearted romantic comedy... a good script is marred by uneven

direction and leads who are not always up to the energy of the project,”

there’s cant for you, cantering.

“So five

hundred times I had to write, ‘I will not step on my father’s

laughs.’” Even more, “make up your mind, that stale

convention or are you gonna live?”

Sports of all

kinds, “a comic they call him,” exiting the Zephyr Club, just

around the corner from Lindy’s, “he really pitches a tent,

doesn’t he.”

The upshot is The Children’s Hour, or rather These Three (dir. William Wyler), anyway a compromised reputation

or the semblance of one, mothers pull kids out of the Anastacia

Macaboy Dancing School.

Preston

Sturges’ The Lady Eve for the counterwooing, and Charade

for the big finale.

Larry Parks

founds his agent on Robert Montgomery arguing sanity with reaches of Hope,

Benny, and Silvers (“not on ya life”).

Elizabeth Taylor builds steadily on the out-of-town girl to a fine comic

understanding.

Halliwell’s Film Guide bears this Donenesque

blunder, “only moderate production values are brought to bear on this

wispy plot which shows no signs of development.”

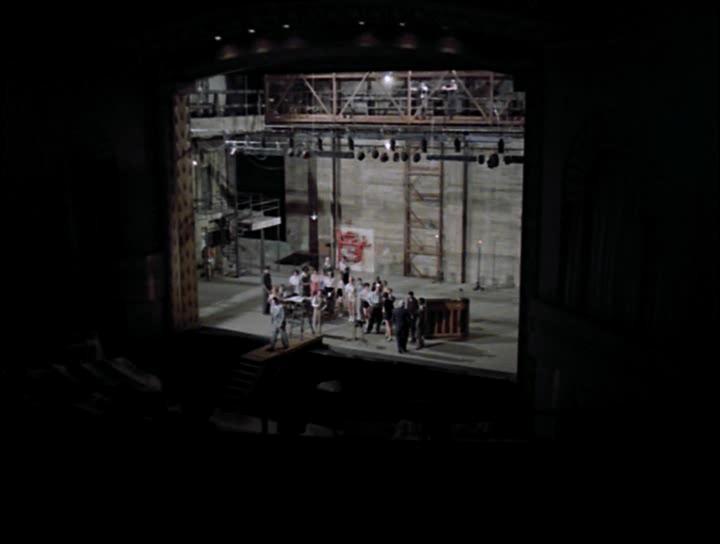

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers

It’s a

thrilling film, not only because it builds to the famous barn-raising dance and

fight to close the first part, followed by a long buildup to the punchline of

the second, but also by reason of Donen’s great technique.

His sang-froid

with CinemaScope lets the frame cut off Jane Powell just below the chin

standing next to Howard Keel before the wedding (with a slight perspective

suggesting an angle of futurity).

A.H. Weiler of the New York Times thought it wiser not to

ask, but it’s all explained in the exposition. Back East where it’s

civilized a man can take his time courting a girl, but who can spare time on

the farm in Oregon when there’s trees to be cut (the bridegroom can land

one within an inch of where he wants it) and land to be plowed (twenty acres in

a day, if he puts his mind to it)?

Donen uses a

sound stage for “Wonderful Day”, the mountains go out of focus when

Powell sings, a breeze stirs the leaves and flowers.

His long takes can be motionless like the farmhouse interior as the brothers

are introduced, or circular in a characteristic motion (slow and back around)

like “Lonesome Polecat”, or just plain ferocious as when he leaves

Keel up a tree to frame Powell in a window (“When You’re in

Love”) and returns to him afterward, all in one shot.

“Goin’ Courtin’”

is done in three shots, the brides’ song in two, “Lonesome

Polecat” in one.

The set

decoration is noteworthy as one department (the M-G-M orchestrations are

another, with banjo) of a solidly realized picture down to the smallest

details. The disorder and refuse in the farmhouse are quickly seen and quickly

mended, these honest farmers who dance up a barn (and fight it down again,

goaded by vicious townsmen) are not exactly the “hix”

fondly lauded by reviewers of the time.

Deep In My Heart

A

theory of criticism.

As

distinct from a work of biography.

An artist is

present in all of his works, they constitute his biography.

The perception of

this is criticism.

Sigmund

Romberg, seen through the prism of Singin’ in the

Rain.

Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times was a colossal

ass who found Jose Ferrer in the great central number “labored and

humorless” (cp. The

Last Tycoon, dir. Elia Kazan).

Halliwell’s Film Guide praises the script, funny the writer knows from. Sarris, “virtually a complete disaster.”

Funny Face

The

photographer’s art.

Opposed to it is

something called Empathicalism, a philosophy to Frenchmen.

Aspects of the

theme are from Minnelli’s An American in Paris and Curtiz’ White

Christmas (“Choreography”), Indiscreet and

Resnais’ I Want to Go Home are very useful analyses.

Nabokov’s

“Ode to a Model” is particularly apt.

Kiss Them For Me

A perennial theme

for Donen, servicemen at home (On the Town, It’s Always Fair

Weather, but also Damn Yankees), treated to a scouring limit that is

transcended the way shellshock or combat fatigue is numbed over and left

behind, in fact it’s like just what it says it is, the better part of a

week in San Francisco away from Navy flying in 1944.

Critics had no

comprehension of this at all, whatsoever.

Indiscreet

It must be

properly analyzed to be seen at its true measure, critics have never done that

but found the film laudable and “thin”, the play

“fluff”. The complex structure can be seen to combine the husband

and the lover in Lubitsch’s That Uncertain Feeling as one, that

accounts for the overall form in which a deceptive lover is snared and landed,

and the admirable tessitura of London and international society (the lover

lectures on “hard currency” not bound to another, takes a job with

NATO in Paris while he conducts his love affair with a West End stage actress,

and finally delivers a “monetary pact” in New York).

The result of all

this is one of the most beautiful color films ever made, a preoccupation of

Donen’s, and this has not been noticed either.

Once more, with feeling!

Scientific

American and Nature

periodically try to explain art as a neural function or some such nonsense,

that’s half the film.

The other half is

the board of trustees, God bless them.

Cassavetes’

Too Late Blues is on the same beam, per Duke Ellington.

Liszt and an

uncredited Berlioz have a hand in this.

Surprise Package

An American mobster with his hand in everything is deported to a Greek

isle with nothing, there the King of Anatolia exiled by the People’s

Republic lives comfortably on the crown jewels, the gang sends a moll instead

of the dough.

“I read it

in a book.”

“What book?

I know your whole library, you got Robin Hood and Peyton Place!”

The mysterious

formulation of Dassin’s Topkapi

is partially accounted for by this Runyonesque

fantasy so exhilarated by its location it might by turns be Born Yesterday or The Lady from Shanghai at any moment (it opens like Goldfinger’s

mob confab).

“Love is a

surprise package,” says the song by Sammy Cahn and James Van Heusen.

Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times pronounced it “chaff” and “witless”. So Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“flat and feeble”.

A heist is in

order. “Aw, I’m sorry. Is that the only crown ya got?” Cf. Frankenheimer’s The Train.

It might be

Huston’s Beat the Devil or

Renoir’s Le Carrosse

d’or, which is how it ends.

The joke is see you in C-U-B-A.

The Grass Is Greener

The man of money

(half a crown) intrudes upon the private apartments of a

National-something-or-other “stately home” (Coward) and takes the

Countess to London and the Savoy.

The Earl objects,

there is a duel.

Wilde and some

others figure in the script, which is acted by a nonpareil cast.

Charade

Consequences of

an assassination, its motive (the MacGuffin), “and twelve Princess Grace commemoratives...”

Alfred Hitchcock

(The Man Who Knew Too Much, To Catch a Thief, The Lodger etc.) and Robert Siodmak (La Crise est finie at the Comédie-Française, where the title

signifies “Happy Days Are Here Again”).

The

mirror of Arabesque.

Bosley

Crowther of the New

York Times, “an interesting element in the picture is Henry Mancini's

offbeat score, which makes the music a sardonic commentator. I'll go along with

what it says.” Robert B.

Frederick (Variety),

“has it made.” Pauline Kael,

“high-style kitsch.” Time Out, “mammoth audience teaser.” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader),

“perfectly crafted”. TV Guide, “charming”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “satisfying sub-Hitchcock

nonsense,” citing Arthur Knight, “sinister”.

Arabesque

It takes an

Oxford don to solve for x, the year

before Losey’s Accident.

A

visit to the eye doctor, a new prescription.

The

Hittite inscription that isn’t one but a mere goosing, the prime minister

who isn’t one but a dead ringer, for purposes of state. A great work of art on the subject, closely

related to Charade, intricately

wrought on themes of Hitchcock (Foreign

Correspondent, Marnie etc.) and

Welles (The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin etc.) to convey a sense of

art for art’s sake (Binder, Dior et

al.).

Profound

score by Henry Mancini. A British picture (Challis cinematography, Dempster

camera), Anglo-American at least. The swans do not “fly high in the

kingdom of Vesta” but swan about on the river

Isis.

Grace Glueck (New York

Times), “apparently goes on the theory that in a chase movie the plot

should only be used as a framework, for visual entertainments.” Variety, “fault lies in a shadowy plotline and confusing characters.”

Tom Milne (Time Out), “very

sub-Hitchcock.” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “not quite the tour de force”. Film4, “convoluted

and often ridiculous.” TV

Guide, “mindless, absurdly complex”. Judd Blaise

(Rovi), “airy, intentionally superficial comic

adventure.” Halliwell’s Film

Guide, “utterly forgettable” (citing the Monthly Film Bulletin to much the same effect, also Sight and Sound, and Robert Windeler in rebuttal, “a strikingly visual chase and

intrigue yarn”).

Two for the Road

This has a real,

functional surrealism tied to Albee (Everything in the Garden) in its

latter scenes, which is prepared in the American tourist couple and daughter.

The wife’s affair is also signally betokened by the husband’s

highway fling, this is the way in which his career advancement and her

pregnancy are understood (Clayton’s The Pumpkin Eater is the major

precedent).

The theatrical

device of intertwined cars and hitchhikers is a suture from the playing space

of Miller’s After the Fall, a continuous fluid structure is obtained by way of

Welles’ flashback organization in Citizen Kane.

A subtle taste

for Antonioni, the refined study of Hitchcock in Charade and Arabesque,

the screenplay by Frederic Raphael, and the actors, give an account of marriage

prefiguring Nabokov’s Ada in certain respects.

The four motifs

wind through France on a walking tour of architecture and a girls’ choir

bound for a music festival, a roadster holiday at a venture, a trip to Greece

with an old flame’s new family, and a business trip to St. Tropez.

The plug-in Venus

from It’s Always Fair Weather, “Chantilly Glaces!” on sale in that

city, the patron as Old Man of the Sea, and everywhere a swiftness of invention

brought to immediacy by the stylistic conception, make for a masterpiece of the

highest water.

A spoof of

Americans abroad takes the measure of Tati’s postman obliterated by

American efficiency, and Melville’s Parvulesco

aghast at American female dominance.

Various hurdles

are dispatched with a sense of time configured as momentum, and this is to be

understood as an imaginative principle at work, the meaning of surrealism.

Cat on a Hot

Tin Roof (dir. Richard Brooks)

figures in the Americans’ spoiled daughter. On the road that leads to Cap

Valéry, her father is “the largest pocket of untapped natural gas known

to man.”

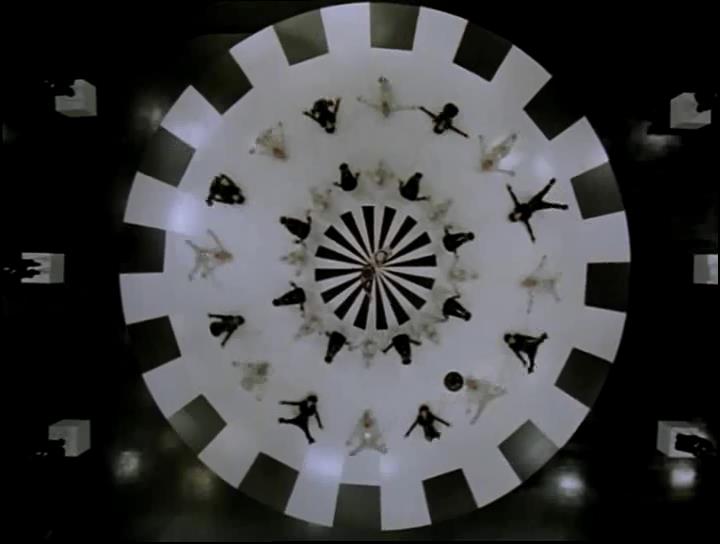

Bedazzled

A C. of E.

catechism, Michelangelo painted it for the RC, Cook

& Moore & Donen filmed it.

The opening (and

closing) “spin” motif was paid tribute by Robert Altman in Prêt-à-Porter.

One point of

departure for the devil’s tricks is a Twilight Zone episode

starring Luther Adler, “The Man in the Bottle”, written by Rod

Serling and directed by Don Medford.

American

audiences used to get this sort of thing every Sunday morning from Insight,

but not on this lavish, sumptuous scale, with some very elegant ideas on color

cinematography by Donen.

You have love

envisioned from the standpoint of the unrequited working class, the frustrated

intelligentsia, and the rich but deceived. You have the gratuitous nightmare of

the pop star, featuring the title number as not sung by Peter Cook. You

have the sex life of a cicisbeo. At last, you have the gorgeous flummery of the

nunnery.

Interspersed are

really classic bits on the seven deadly sins, what are known as “quick

takes” (Envy is a bitching queen, Lust is Raquel Welch).

Staircase

The two parties

in this terribly undervalued comedy are hairdressers for the far outer reaches

of London, each facing a moment of truth. Charlie (Rex Harrison) is up before

the judge on a charge of willful impersonation of the female, to wit Mrs. Whatsit launching a battleship, in an ad lib revival of his

cabaret act, or perhaps the bleedin’ young

copper what pinched him has still further evidence of incitement to depravity.

Harry (Richard

Burton) has gone completely bald, which as Charlie gleefully points out simply

won’t do in the tonsorial line.

They care for

their mums, Charlie’s is silent, voracious, institutionalized, and calls

him a Sodomite to his face. Harry’s is vociferous, arthritic,

incontinent, and cries when he leaves the house.

The litterstrewn park with Coney Island sunbathers, two having

it off after a sudden rainshower, the litterstrewn street, Charlie’s pickup of an evening,

tears, recriminations, courage for the new day.

The Little Prince

Only a film

director can grasp the full import of the experience symbolized, and those who

are familiar with that experience by report.

He draws an

elephant inside a digesting snake, it’s taken

for a hat, charming, exotic, disgusting or tiresome.

His plane crashes

in the desert. A series of illustrative episodes describe his difficulties, but

the thing is a constellation.

Lucky Lady

After the rare cri

de cœur of The Little Prince, Donen

strikes back at the Philistines.

The great John

Held, Jr. cartoons are endpapers of the high life, the film depicts its

furnishings. A note from Truffaut’s Jules et

Jim supplies the partnership, deflecting George Roy Hill’s Butch

Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (also, a critic has noted The Sting).

Tijuana bar money

comes from running wetbacks, there’s a fortune in contraband. Rumrunners

rise high, tangle with a near-psychotic Coast Guard skipper, and beat the East

Coast mob in the battle of San Nicolas Island.

Altman took a

turn at this as homage in Popeye, with another view.

The dullness of

the underworld is plainly depicted in Seiter’s Borderline.

Movie Movie

Donen’s

masterpiece by Gelbart & Keller on the Depression

and the war years twice over, from Body

and Soul (dir. Robert Rossen) and 42nd

Street (dir. Lloyd Bacon), with Zero

Hour (“his plane was his mistress”) in between, the trailer.

What it was all

about, a great work of analysis. “Gee, Simpson, if you’re what

orphans are like, there oughta be a whole lot more of

‘em.”

“Kitty,

I’ve been around a long time, and you can take it from me that

Broadway—is a queer racket.”

A certain note is

sagely adduced from The Boy Friend

(dir. Ken Russell).

Vincent

Canby of the New York Times, “it seems so effortlessly funny that I suspect that the

real intelligence and discipline that guide the project will be overlooked.”

Variety, “the conception is a

mess, and it shows.” Time Out,

“dire script... flat performances... pointlessness...” TV Guide, “you have to know a lot

about the movies upon which this is based to glean the most out of the

humor.” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “the screenplay relies too heavily on facile non

sequiturs, but Donen has the shape down pat: squared off, symmetrical, and

wholly self-contained.” Craig Butler (All Movie Guide),

“ultimately just a silly exercise.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “pretty patchy... golden

moments...” citing Richard Combs (Monthly

Film Bulletin), “swallowed in its own idiocy.”

“Age

before beauty,” says George Burns, “after you.”

Saturn 3

The entire film exists

to posit a single image, that of a man who straps on explosives in order to

destroy a robot.

A remake of The

Grass Is Greener and much imitated.

Blame It on Rio

The problem as stated

is from Matisse, it builds to a climax of farce and is reconciled per Mozart, the equation is “emotion recollected in

tranquility”.

The narrative

structure is derived from Bergman by way of Allen, and the keynote is the

“I Left My Hat in Haiti” number in Royal Wedding. That complicated “stage” piece

is directly transposed into a “realistic” cinema format in one shot

dollying right onto a street musician.

Above all, a

masterpiece of lighting, at a time when several directors (Rafelson, Mulligan)

were discovering the implications of cool colors briefly propounded by Huston

in a single shot of The Man Who Would Be

King. The structure presents a certain problem of harmonization.

This is resolved in subtle color combinations, organized as a scale of pure colors

modulated through shade, with glints of pure sunlight sometimes in the

background (or highlighting the foreground), and cool shaded colors

predominating.

The range of his

palette gives Donen an opportunity for analysis and representation of Rio colors,

and he uses it to full advantage. His compositions grow in subtlety and

complexity, giving very deep and very fresh color combinations.

The coda adds a

little sauce to this variation on a theme, with a gag about being young twice.

Love Letters

Donen’s

color harmonies are of the deepest and rarest. The beauty of that is,

television’s always had a hard time coping with color composition

(compare the gentlemanly chiaroscuro of black and white), and this is an ABC

production.

Prokofieff: Sonata #7, Op.

83, 3rd Movement: precipitato

Split-screen,

various angles of attack, a group of monitors, exhaustively realized up against

Stravinsky and Bartók, adequately.

Mischa Dichter, “five

cameras... one take.”