Mystery Sea Raider

Enigma of the

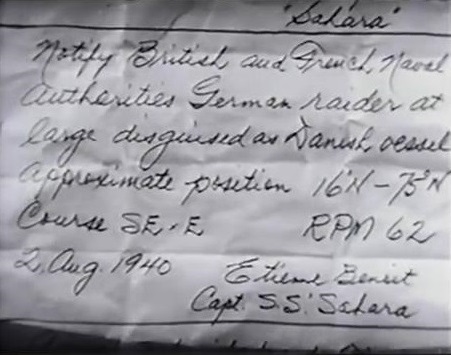

S.S. Apache, hired off “the

mudflats of the Hudson” in hard times by the Nazis of Greater Germany for

service in the Caribbean as a prison ship and pirate vessel under the Danish

flag, skipper and crew sequestered below.

Cp. Seas Beneath (dir. John Ford) and They Dare Not Love (dir. James Whale),

later there is Mystery Submarine

(dir. Douglas Sirk).

TV Guide,

“standard melodrama-intrigue film”.

The Devil Commands

Discovery of

brainwaves and the electroencephalogram “as if a magic lantern threw the

nerves in patterns on a screen.” Following on this, “controlled and

scientific communication between the living and the so-called dead,” the

comparison is to radio, the spirit medium whose brain is eléctrico might serve as an

aerial.

“If you can

do what you’re trying to do, you’ll own the world.”

Thus speaks the

fraud, whose victim is a dull-witted laboratory assistant anxious to hear from

his late mother on a weekly basis, puppet-apparition and all. Medium and dupe

together just educe the dead wife’s brainwave, too much for the clod, his

canny exploiter persuades the scientist mad with grief to pursue his researches

on the lam, as it were, at a house above the New England seacoast.

Filmed

after the fall of France, released early in 1941. Don Siegel takes up the motif after the war in Night Unto Night.

T.M.P. of the New York Times found nothing in these

poetic themes from Robert Browning and T.S. Eliot, “a hodgepodge of

scientific claptrap,” too much for the clod. Same with Tom Milne (Time Out), “Dmytryk injects what

style he can”. Leonard Maltin,

“improbable but intriguing... predictable... absurd”.

The daughter narrates.

“My father never hurt a living person in Barsham

Harbor. Never.”

The sheriff takes a professional interest, “ordinarily I don’t pay

much attention to what people say, I

figure they’ve got to talk about something,”

cp. Doctor Blood’s Coffin (dir.

Sidney J. Furie) or The Plague of the

Zombies (dir. John Gilling).

“My father

had become a very strange man.” De Chirico masks for the grand séance,

Lang’s Metropolis, the vortex

of Quatermass and the Pit (dir. Roy

Ward Baker), a mechanical voice calls the scientist’s name, death of the

spirit medium, reconcilement with the daughter.

Milne praises

Karloff as “reliable” and arrogates this to Hitchcock’s Rebecca. No mention of Anne Revere and

the rest of the cast.

Down at the

little post office, a vengeful mob sets out, led by the late

housekeeper’s husband.

The daughter in

the mask, séance da capo, this time clear as a bell, the

voice, destruction and death...

Hal

Erickson (Rovi), “cheap but lively”. TV Guide,

“not entirely successful.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “modestly effective”.

Confessions of Boston

Blackie

The faux

Augustus, plaster saint, bears within the murderer first, and then his victim,

who is the fabricator of the lie.

Thus

Dmytryk in 1941, a simple case of art forgery. “Well, it was so beautiful I can’t

tell it from the original, so I feel that I saved the ten thousand.”

Leonard

Maltin, “delightful”. Hal Erickson (Rovi),

“superior series entry.”

Without a doubt,

“the only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.” Blackie,

who incredibly misses hitting the assassin “by that much”, is

charged with murder even in the absence of a corpus delicti, so to speak.

A thing of

beauty...

Mona’s

badger game in Blackie’s apartment follows Mr. Kane’s Rosebud rage

by a factor of May-December.

|

BOSTON BLACKIE BAFFLES POLICE! |

Back

at the hideout, De Chirico.

“You’ve got a little Gestapo in you.”

“That’s why you’re not on the

pistol team.”

“A

million dollars’ worth of brains on a dead end street.”

“You’ve

got more signals here than a World Series pitcher.”

Hitler’s Children

“For

Hitler we will live,” they sing, “and for Hitler we will

die,” the Hitlerjugend.

“The sun that

shines for us is Adolf Hitler,” says the swearer-in.

German boys repeat this rubbish.

“My

Savior! My

Führer!”

Side by side in

Berlin, 1933, the American Colony School and the Horst Wessel Schule (Bonita Granville and Tim Holt are students in the

one and the other respectively).

“You

shouldn’t be seen over here, what would Dr. Schmidt say, and dear Mr. Schicklgruber?”

A

nimble account of “A Dissertation upon Roast Pig”.

Goethe,

“and those who live for their faith shall behold it living.”

The Jungvolk, bound and gagged for it. From here it’s straight on

for Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone.

“You are barbarians, aren’t you, even

the Rhodes Scholars among you.”

Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times,

“muffs completely a fine opportunity”.

Variety,

“forcefully brought to the screen”.

The

Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “simple but effective”.

Leonard

Maltin, “engrossing exploitation film... quite sensational”.

TV Guide,

“far from an evenhanded depiction”.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “artificial melodrama”, citing Howard

Barnes of the New York Herald Tribune,

“a curiously compromised production”.

The ending is a fine homage to Curtiz’ Casablanca.

Captive Wild Woman

Monkey nuts in

reverse turn a gorilla into a beautiful girl with charms to soothe the savage

breast, a great boon to an animal trainer filling in for Clyde Beatty at John

Whipple’s Circus.

An innocent girl

must be drained for this, and a smart dame gives up her brain.

Beatty himself is

seen in the cage, wielding a chair and whip and revolver.

By mistake, the

ape is killed after saving the trainer’s life. A similar erroneous notion

led T.M.P. of the New York Times to pronounce the film “in

decidedly bad taste.”

Jonathan

Rosenbaum’s Chicago Reader blurb inaccurately describes the plot.

Behind the Rising Sun

The true

nuttiness of Japan’s dream of world conquest is quite vividly seen (cf.

Santell’s Jack London), Dmytryk takes some considerable time with

it, to let the horrors bathe his film fully and then, only then, the true

position, and by then of course it is too late for Japan.

In

the middle of the war, the war in Tokyo.

A

great masterpiece not quite seen as such by T.S. of the New York Times

(“an honest and effective film”).

“A

good drama of inside info” (Variety).

Halliwell’s

Film Guide has “outrageous

wartime flagwaver”.

Tender Comrade

Dalton

Trumbo’s tale of the home front girls who worked in the war plants. Almost unbearably affecting and insanely maligned.

Trumbo represents

himself as Jones (Robert Ryan), who wants to take his wife (Ginger Rogers) back

to Shale City, Colorado after the war.

The girls share a

house for economy’s sake a short walk from USC, where Trumbo attended

classes.

Murder, My Sweet

Dmytryk, between Huston and Hawks.

The

irresistible rise of a showgirl from Florian’s on Central Avenue to a

vast manse in Brentwood.

She’s

blackmailed by a fashionable quack on Sunset, who dies.

Other

people die to make her comfortable.

Marlowe

gets sucked in on the original missing-persons call.

Philip

Marlowe, perched just above the city.

Hitchcock

takes note of the hypo-induced dream sequence.

Welles

has been cited as an influence (Citizen

Kane).

Back to Bataan

Its

clear, plain sailing of form consists in historical fact. The

fall of the Philippines, guerilla fighting under the Japanese occupation, the

return at Leyte.

But

purely formal difficulties are present, as the reviews attest, in the

construction of the film as very small scenes fitted together in fragments to

give a prismatic feeling of the events and permit tremendous scope and range in

what has been taken for a modest battle pic since the day Bosley Crowther first

saw it and titled his review, “More heroics”.

The

death march is just stumbled on when the guerilla party miss the significance

of the school principal’s execution. The schoolteacher’s imperious

command of history gives way before a student’s object lesson.

Back

to Bataan was up to the minute and

far ahead of its time. The difficulty of rendering Axis warmakers had been

addressed face-on by Riefenstahl, the charge of racism is absurd, Dmytryk has the best actors in Hollywood for his Japs. On

the other hand, his patriotism is that of Cummings’ Olaf, who “will

not kiss your f.ing flag”.

Cornered

It

begins in London, moves to the coast of France, then Marseilles, Berne and

Buenos Aires (Hotel Regent, Bar Fortuna). None of these places is very real,

tantalizingly so. An Argentinean subway car marked Florida comes into view,

briefly, and a night exterior of shops along a street is an approximation.

Composition doesn’t govern the shots (and in this it curiously

anticipates Pollack’s Jeremiah Johnson),

it can’t be called a film noir even though it directly figures in

Reed’s The Third Man and Maté’s D.O.A. quite visibly.

The

RCAF demobs a pilot (Dick Powell) shot down and imprisoned, his French wife of

twenty days was killed, he pursues the Vichy official (Luther Adler) who

betrayed her and who is thought to have died, or rather he intends to go to

France and settle her estate but the chains of bureaucracy and misinformation

block his way so terribly that he must give no quarter to any thought of

accommodation, his persistence and determination shake off every dead end, he

meets the man in Buenos Aires.

Composition

doesn’t even enter into the plot, the circumstances or the action. There

is no well-placed detective story with a hero bobbing and weaving, only the

simulacrum of a Fascist group not very far from Hitchcock’s Notorious,

and a man who has a pistol and a scar, his bitterness and smoldering impatience

are all the surface there is, not even Nina Vale’s enticing skintight

black lace is anything more than one element of a turgid nightmare.

“Unreal

cities”, and yet the state of mind is pierced by the hot charred remains

of a house set afire in the act of burning some documents that must be sought

out amidst the blackened beams and ashes.

A

Maquis leader, a Swiss insurance company, Walter Slezak as a nefarious tour

guide, some Argentinean anti-Fascists, and the Buenos Aires police, also people

the landscape.

Till the End of Time

The

unattainable achievement at the outset is the whistling down of a Marine

corporal at the end of the war to his home in “the growing city of the

world”, Los Angeles, with the greatest art Dmytryk attains it precisely.

“Well, Cliff, you’re—you’re back! You’re back

from the thing!” Which perhaps is where Christian Nyby gets his title. It takes Bergman all of Wild Strawberries to achieve the same

result, and then it is only a dream, a sufficient dream to balance the initial

nightmare.

It’s

the song, of course, from Chopin’s A-flat Polonaise. It’s in the

jukebox and on the radio, Leigh Harline orchestrates

it (also “There’s No Place Like

Home”), the complete works, like Dmytryk’s film. The shakes, “let them look.”

“And

if they don’t like it, let them kill themselves.” The dream that

ends in nightmare back home, cf.

Dieterle’s I’ll Be Seeing You.

The sheer waste of time, if nothing else, spent going to war, from a civilian

viewpoint.

FDR’s troops. “If Gunny can show me a book that’ll

teach a guy how to win a boxing championship with no legs, I’ll read

it,” cf. Zinnemann’s The Men. “Live on the beach and

swim, and lie on the sand in front of a fire, yes sir, that’s what

I’m going to do.” To put it another way, “where do I fit

in?”

“You’re

the velvet.”

Leonard

Maltin, “solid, sympathetic”. TV Guide, “had enough stuff to make

it ring the cash registers.”

An

extraordinary recapitulation of l’entre-deux-guerres and the war lately ended

concludes the film. “If worse comes to worse we’ll raise women,

too,” the Swan Club on Western.

Halliwell’s

Film Guide,

“downbeat”.

So Well Remembered

There

was a Kaiser, he had a daughter, that is the cultivated image principally, by

an extension of surreal processes they are mill owners in Lancashire, lording

it over a slum-ridden town up to 1945, with a twenty-year interregnum that

corresponds to the elder Channing’s prison sentence.

Their

opponent is a town councillor, alderman and then mayor, who also runs the Browdley and District Guardian.

These

are the metaphors, this is the construction. The film is a flashback from the first

intuitive victory celebrations in the town to the beginning of the story in

1919.

Crossfire

Who

killed the Jews of Europe? It’s a burning question, in 1946. The G.I. Joe

who moved too slow, the fellow who went off on a drunk with a B-girl?

The

Jew-hater, that’s who, then he kills a witness.

A

very complicated position is expressed in a very complicated film, andante

furioso, generally likened by critics to Gentleman’s Agreement (dir. Elia Kazan), which really is

about anti-Semitism.

Obsession

FDR’s

statue in Grosvenor Square decides the issue, framed by two club conversations

on England’s woes and America’s ascendancy, which are the basis of

the argument.

With Clouzot’s Quai des Orfèvres, an

important source for Columbo.

A deep, yet serene, and very brilliant masterpiece

on a theme that carries over into the critical perception, a case of jealousy

that prompts a perfect murder, ideal even.

Nino

Rota’s score is one of the best, Variety reports that the play

folded quickly, it makes a witty, lively screenplay that Dmytryk films with the

greatest attention and ease, conscious at every moment of the lightness in his

madman and the seriousness outside his purview, which does not include the

silly gorgeous wife and her latest, a Yank.

Give Us This Day

Snow and the building racket and the Great

Depression.

Dmytryk

ahead of Rocco e i

suoi fratelli (dir.

Luchino Visconti) and Le mani sulla città (dir. Francesco

Rosi), on New York, filmed in UK during one of America’s “periods of historic madness.”

A great likeness of Gian

Maria Volonté in the role, Sam Wanamaker.

Cp.

The Stars Look Down,

dir. Carol Reed. Perhaps the most arcane influence is on Once Upon a Time in America, dir. Sergio

Leone.

Bosley

Crowther of the New

York Times, “standard hard-luck story, rather heavily composed of

stock woes.” Variety, “the expert hand of Edward

Dmytryk’s direction ensures faithful atmosphere.” Jonathan Rosenbaum, “in some respects

this is Edward Dmytryk’s best film.” Hal Erickson (Rovi), “terminal sanctimony.” Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“a very curious enterprise for a British studio,” citing Winnington and Mallett of two

minds.

Mutiny

The

domineering mistress, wholly unscrupulous and perfectly hypocritical, fetched

back from Paris on the promise of an old lover’s advancement, is an

adequate image of impressment in 1812, add to that a ship’s anchor of

solid gold for the United States raised by private French subscription, so

disguised to run the British blockade, and you have the temptation.

Crowther

thought it was a joke and himself “the outside

observer who, despite Technicolor, is unimpressed,” which he probably

meant as another.

The Sniper

A

man wronged by some woman in his past (so goes the theory) takes vengeance on

the likes of her with a carbine.

Much

later there is Dmytryk’s Bluebeard, The Sniper makes a case

for psychiatric care early on in such instances, and sure enough there is

Siegel’s Dirty Harry to deal with the same mess in the same

locale, as predicted.

Crowther

(New York Times) thought this was footling and “a dignified

excuse”, he looked for “the menace and the understanding of the sex

fiend”.

Halliwell

thought it was blondes, not brunettes, and says it “seems quite routine now.”

Lt. Frank Kafka and Sgt. Joe Ferris have the case.

This

is very touchingly constructed, the aged landlady pampers Asa, her cat, but

expects him to do his job like everyone else, catching

mice in the basement (Asa watches wide-eyed as the sniper burns evidence in the

furnace). The lady supervisor at the job is perfectly hard and belittling, women generally are seen as easily cruel and

heartless, if they’re not laughing and in love, even a mother with her

son. This of course is the sniper’s view, he burns his right hand on a

hot plate to circumvent the temptation, providing the image that is perhaps the

most telling (unless it is the painter shot on the side of a factory stack as a

witness, or the sniper caressing his carbine), “let my right hand forget

her cunning.”

The

murders are quite matter-of-fact, death from a distance, shattering glass and

dropping the girl at once.

Fleischer

in The Boston Strangler has again the roundup of perverts that is a dead

end, the police psychiatrist puts the detectives on a

more direct trail that leads to the sniper seated on his bed, carbine in his

hands, a tear on his cheek rather than some “less sad secretion”

otherwhere.

Eight Iron Men

How to get a medal in the war. It takes some doing, after some talk and red tape,

lobbing ‘em in, pulling back and so forth, you put a pineapple in the slit

and bring the slob home.

It

was a play at some point, Dmytryk doesn’t say how.

“A

dismally meretricious thing,” said Bosley Crowther.

The Juggler

Carpenters,

plumbers, they have jobs in Israel.

He

all but kills a Haifa policeman, psychotic since the Nazis, at times.

Formerly a star at the London Palladium and

elsewhere, a refugee.

The

theme of artistic invincibility is also in Russell’s Dance of the Seven Veils.

The

back page of the newspaper stays burnt despite the abracadabra, at the same

time on a kibbutz the cows come home.

“If

all the old men could hire young men to die for them, a young man could make a

very nice living.” Also, “hope is a naughty word these days.”

Kirk

Douglas juggles and clowns, his entrance pratfall is Lon Chaney’s in Laugh, Clown, Laugh (dir. Herbert

Brenon), among other things.

In

the end, one is at home, despite all appearances to the contrary.

Bosley

Crowther asked, “what’s

such a handsome girl doing unmarried on a community farm?” He could

supply no answer, the film “may not be

consistent dramatically.”

Filmed on location in town and country (Nazareth,

Galilee). The basis of the

screenplay is Capra’s Meet John Doe

as much as anything else.

“Well-meaning”,

Halliwell’s Film Guide thinks.

The Caine Mutiny

To put your oar

in is the main subject as it pertains to a naval captain’s reliance on

his officers, without which he becomes isolated and ineffective.

Despite the

clarity of Dmytryk’s telling, the film is variously misunderstood as

structurally inept (New York Times) or thematically jejune (Time Out

Film Guide).

Broken Lance

Variety lamented an “unnecessary flashback”. A

man serves his three-year term in state prison out West, leaves bitterly and is

escorted to the governor, who with the man’s brothers has a lucrative deal

for him to leave the state. The man tosses the money in a spittoon and rides

home to see the place a dusty ruin. Here the flashback commences.

A requiem for the

West or a long overture to a little theme announced earlier. The New York

Times’ A.W. agreed with Variety and furthermore considered

that “Jean Peters, as the Governor’s daughter, is decorative but

hardly the frontier type.”

The major structural point to be observed is a relationship to The

Caine Mutiny.

The End of the Affair

Obsession (The Hidden

Room), this time under the auspices of Graham Greene. The doodlebug is God’s thunderbolt (cf. Eliot’s “flame of

incandescent terror”), a private dick is put on

the dame after the war, one Savage at 159 Vigo Street.

The civil servant’s wife, an English wife.

The end of the affair is Losey’s Secret Ceremony.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “if you ask us... the story just is not

articulate.”

Boxoffice,

“reflects an intelligent grasp of the subject at hand.”

The Catholic News Service Media Review Office,

“uneven... only intermittently convincing... disappointingly

melodramatic.”

Leonard Maltin, “loses much in screen

version.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “glum sinning in Greeneland;

over-ambitious, miscast, and poor-looking.”

Lenore Coffee screenplay, Wilkie Cooper cinematography, Benjamin

Frankel score, Alan Hume cameraman.

There is subsequently Fellini’s Giulietta degli spiriti

(also Billy Wilder’s Love in the

Afternoon for the detective, a family man).

Pinter’s The Homecoming

(dir. Peter Hall) is another statement of the theme.

Soldier of Fortune

Stravinsky was

stopped on a border in World War I, he was carrying

maps of military installations.

Those were

Picasso’s portraits of him, drawings.

A sad little

story out of Hong Kong, but you have to climb

mountains to find it.

Mrs. America goes

to find her husband, a journalist. The British are no help, there’s an

American smuggler.

The far end of

the Pacific war comes down to this.

Bosley Crowther

was entirely mystified in the New York

Times.

The Left Hand of God

The priest who is

not a priest, his dice-throws save the people from a

Chinese warlord.

This fine anagram

went rather by the boards with Bosley Crowther, it simply didn’t add

up in his New York Times review, the plausibilities and the fictions

wouldn’t jibe.

The Mountain

The wreck of a

jetliner, attempt at rescue, a looting party, rescue of a survivor.

Supremely

well-filmed until Dmytryk lets it go just before the end, because he has the

bigger fish of a surprising confession to fry, and thus a saving work beyond

its supreme analysis.

An

agonizing climb up the south face of Mont Blanc, a true piece of

mountaineering.

Eastwood picks up

the filming in The Eiger Sanction,

Zinnemann the theme in Five Days One

Summer, but it is all one.

Bosley

Crowther of the New

York Times, “flimsy and hard to take... of little account.”

The Catholic News

Service Media Review Office, “unconvincing... makes no sense”.

Leonard

Maltin, “turgid”.

TV Guide,

“a mistake.”

Hal Erickson (Rovi), “compromised”.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “an indeterminate production”.

Raintree County

If

the antebellum South is described as Gone with the Wind, the North is

evoked as a tree firmly planted. Or, as Prof. Stiles might say, “a very

vast idea of the South, more arduous than Jezebel, which might be said

to sweep like Sherman to the sea and there find Daphne quite

transformed.”

Somewhere

in the swamps round about Freehaven, Indiana (Prof. Stiles explains) a single

seed of the rain tree (indigenous to China) was planted at the time of Johnny

Appleseed, and whosoever finds the tree will be endowed with “the secret

of life.” His pupil John Shawnessy expands, “it opens all locks,

heals all wounds.”

Young

Shawnessy is an admirer of Byron. After winning a foot race, he is seen at a

picnic wearing a laurel wreath and playing a reed pipe. These early, youthful

scenes are often formed on Impressionist models, tempered by Eakins and Homer.

The

crux of Show Boat is introduced with dramatic fervor. “Lincoln has

Negro blood in him,” says Mrs. Shawnessy. Indianapolis is described as

“a Copperhead town.” The quest for the rain tree is delayed as

“much too perilous a business.” Shawnessy joins the war to retrieve

his wife and son. The Union must be preserved.

Some

controversy attaches to the screenplay, which is complained of as being not

like the novel. To this day, it is necessary to point out to some in the

audience that they’re watching a movie. In addition, and most

obnoxiously, one must be told about Montgomery Clift’s accident. One is,

to the contrary, amazed by Clift’s performance throughout, and no

impairment is noticeable. Finally, and with characteristic self-deprecation,

Elizabeth Taylor speaks disparagingly of her performance as “chewing the

scenery.” Lucky scenery, and perhaps a tinge of

complaint against Dmytryk for the intensity of the recital on the bed.

Clift’s attention paid is a model for Alan Bates’ (to Janet Suzman)

in A Day in the Death of Joe Egg (dir.

Peter Medak).

There

is an unmistakable influence on Lean’s Doctor Zhivago and elsewhere.

There is a report that top critics maligned the film as beyond contempt. It is

beyond criticism. The pan-and-scan version is as incommodious as that of Ryan’s

Daughter.

The Young Lions

The

German officer who is gradually and completely disillusioned by the war.

The

crooner who goes into Special Services and finally requests action in Normandy.

The intellectual

(he’s reading Ulysses) who marries and goes overseas in the draft.

The second kills

the first, both have in common an acquaintance so hep

she goes to serve in the Office of War Information.

The main

objection of critics was the characterization of the first, “not like the

book”.

Warlock

An ultrafine

essential Western on the outlaw and the gunfighter and the lawman, better still

the criminal and the private operator or contract employee and the servant of

the law.

If critics had

not blinked and yawned, they would not have been so amazed by Henry

Fonda’s performance in Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West

(there is also Vincent McEveety’s Firecreek).

The beautifully

rigorous analysis was lost on them, however, with all its overtones. Directors

from Ford to Eastwood noted it, with its conscious debt to My Darling

Clementine.

Walk on the Wild Side

Dialogue

between artist and client in a New Orleans brothel.

“Did you

buy me that Brancusi?”

“Nobody

every heard of him. I asked the whole City Hall.”

“He’s

a sculptor, darling. Like Michelangelo, Maillol, Rodin, and me.”

“Last time

you told me you wrote poetry.”

“No, I just

echo it. I’m a sculptress, or rather I used to

be, before I fell down the well.”

Hosea and T.S.

Eliot are called into play before Dmytryk is finished with his map of the

affections, the lay of the land.

“It is

incredible that anything as foolish would be made in this day and age”

(Bosley Crowther, New York Times, same day he dismissed Leo

McCarey’s Satan Never Sleeps).

“A

somewhat watered-downing” (Variety).

Time Out Film

Guide follows Halliwell in

thinking Saul Bass has the best of it.

Gene Kelly’s

The Cheyenne Social Club and Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby take

note.

The Reluctant Saint

He rides into the

priesthood on Buridan’s ass like the Great Cham on Bishop Berkeley, Kershner depicts his travails in A Fine Madness, so to speak.

Joseph of Cupertino,

his life and works, an edifying tale of Christian moral doctrine.

Ashby appears to

draw from it in Being There, the

source and wellspring is assuredly Curtiz’ film on the founder of the

order, Francis of Assisi.

TV Guide

saw “the village idiot who becomes a saint... but the stereotyped

performances, unbelievable settings, and lifeless direction hurt whatever

promises are inherent in the material.”

Tracie Cooper (Rovi) has rather “mentally challenged.”

Score by Nino

Rota, cinematography by Pennington Richards.

The Carpetbaggers

The fabric of the

film is made of ceaseless activity on certain models that are conceivable as

symbols only, that is for ease of composition and

clarity, they are all transmuted in the course of it. There is the one sturdy absolute

revelation of “incurable insanity” (Pauline Kael calls this

“pop psychology”) on which the whole thing pivots, that is the

entire lesson of action motivated by fear.

Critics have

always held a different view. Crowther is notably in error regarding George

Peppard’s performance as “expressionless, murky and dull”.

The classic joke

is that the valet is in on the secret, then the wife.

Where Love Has Gone

A

surrealistic examination of the architect as entertainer of rich clients in a

parent firm, then as a partner in civic planning, finally with an understanding

of the mysteries.

The terrible

difficulty of this left Crowther fuming with rage.

Mirage

One

of the great hallucinations on the screen, like being knocked unconscious and remembering

yourself by fits and starts. The structure is most complicated. A witty,

pointed radio script, cinematically aligned to a film

noir style, the homage (scrupulous, unbending) to Hitchcock, all to house a

somewhat difficult utterance. The analogy of poetic construction is usefully

applied throughout in rhymes, internal rhymes, assonances, etc. David Stillwell

(Gregory Peck) meets a girl (Diane Baker) on the stairwell during a blackout,

but the sub-basements turn up missing.

It’s memory he’s wanting. In a bookstore window he’s struck by

two books, The Peace Scare and The Dark Side of the Mind. He buys

a copy of the latter, goes to see the author, a prominent psychiatrist, using a

footnote as a reference. “You were referred by a dead man,” says

the genius (Robert H. Harris). Amnesia doesn’t last two years, he

explains, two days maybe, and throws Stillwell out.

Our

man now follows on the heels of Mr. Arkadin by hiring a private detective

(Walter Matthau), whose first case this is, to trace

his own identity. As they descend a plaza escalator, the camera on the next one

descends with them. At Stillwell’s apartment, the refrigerator is full,

though it was empty before. The closet is empty. “Brownies” are

proffered in explanation.

They

go together to Stillwell’s office, which doesn’t exist, and pass in

the corridor the office of Charles S. Calvin, Attorney-at-Law, who fell to his

death during the blackout. They examine the stairwell.

A

brutal, bespectacled thug (George Kennedy) is after Stillwell, who emerges from

the ruckus with a key and a keychain bearing the image of the Western

Hemisphere and a motto, THE FUTURE IS HERE. This is the company motto of

Unidyne, Stillwell is a cost accountant. The trouble is, he says, “I

don’t know what a cost accountant does.” The desk security man

knows him, the man with the funny name, Joe Turtle,

it’s off to his apartment. Turtle’s dead, another thug (Jack

Weston) thrusts a bloody pistol into Stillwell’s hand. “Better take

this, you might need it.”

The

girl in the talkative stairwell is confronted with the deed, “a portrait

of the man you work for... you know the artist by his work.” She says

“there was nothing I could do to stop it.”

To

avoid the police, they duck into a neighbor’s apartment. No-one’s

at home except a little girl, who serves them imaginary coffee. “Where

did you learn to make such good coffee?”, they

ask. “Television,” she tells them. “It’s coffier

coffee,” they agree.

Dmytryk

is just getting warmed up with this dense situation, which is itself in

counterpoint to Stillwell’s reviving memory, introduced as unprepared

inserts or cutaways, the unprepared flashback.

He

tells the detective he works for the Garrison Company, but none exists. There

is a Garrison Laboratories in the Capra-sounding town of Brewster, California,

run by Charles Calvin’s peace foundation.

Josephson

(Kevin McCarthy) rears his head, a work chum, formerly head of the

physiochemistry department at Unidyne. And all the while Stillwell is

struggling to recover his past, the girl from the stairwell

(who evidently knows him somehow) claims his future. “Promise

you’ll love me, David, promise me.”

Two

hoods from “the Major” make a play, Stillwell grabs one, threatens

to kill him. “I’ll save you the trouble,” says the other,

pulling a silenced trigger.

Now

you have the idea, this is very close in style and substance to Seven Days

in May, North by Northwest, The Big Sleep, Charade, Three

Days of the Condor, etc. Dmytryk is now ready to begin in earnest.

Stillwell

pursues his investigation, but finds an old derelict blocking his progress up

the steps of a building. After hearing the old man’s harangue, Stillwell

retorts upon him, “I didn’t ask for your references, all I want is

for you to move.”

He

finds the detective murdered, and smashes up the room in his frustration like

Kane. The old man turns up spruce with a gun in his pocket. Stillwell makes his

escape by conversing with a dendrologist about the gingko amidst a juvenile

field trip to Central Park.

Josephson,

the office chum, accosts him there, what they want is on a piece of paper

Stillwell must have upon his person. “What if it’s not in my

pockets?”, asks Stillwell, not knowing what it

is. “You’re all alone, David,” Josephson says,

“there’s nowhere for you to go.” The old man appears, and one

of the thugs. The old man is run over, Stillwell escapes, amid returning

memories of a conversation with Calvin in the country somewhere out West, to

the psychiatrist’s office again, where he is told “a doctor

can’t afford to stop at a street accident anymore.”

This

is The 39 Steps, of course, and Spellbound, much changed. Now the

beans are spilled. Garrison Laboratories is a radiation lab, most of it

underground. “I’m a physiochemist,” Stillwell remembers, who

worked on level SUB 4, and before that at Unidyne. The psychiatrist describes

amnesia as “putting a bandage on a bruised toe,” and adds,

strangely, “these are strange times.”

Stillwell exits with a curse on his lips.

CHARLES

CALVIN IS BURIED, reads the front page headline. He

fell 27 floors from his New York office.

The

Major (Leif Erickson) is the head of Unidyne. Calvin’s peace foundation

was only a front to house top scientists working on ways to neutralize atomic

radiation for ostensibly peaceful uses. Stillwell found a formula, went to New

York, learned Calvin’s secret, set the paper on fire rather than see it

fall into the hands of the Major for military use. Calvin clutched at it, went

out the window by misadventure. A clean bomb would cut down the overhead in

human statistics, says the self-described “cost accountant”.

The

girl in the stairwell shoots the gun-wielding thug, Josephson grabs it.

Stillwell persuades him, against blandishments of security and wealth, to call

the cops.

“I

believed in Charles Calvin so much,” Stillwell avows, “I forgot he

was only a human being.” “Help me, David,” says the girl,

“please help me.” He replies, “We’ll help each other.

That’s really what it’s all about anyway.”

Or,

as Benjamin Franklin put it, “we must hang together, or hang separately,

surely.”

Alvarez Kelly

The

Irish señor is roped into the cattle raid on Grant so much admired by

Abe Lincoln.

There’s

a whole story here about the South after years of war, the kind of man Kelly

is, and the one good raid that feeds the Rebs for a time. All of it is very

mysterious and abstracted, as well it might be.

“Script

problems” are often cited in reviews of Alvarez Kelly, it’s

not so simple as that, when you look at it.

Anzio

A very grueling précis of the war “from China

to Italy”. The antagonists

are Field Marshal Kesselring and an Official War Correspondent named Ennis.

The

battle is understood in its effects as the long descriptive middle section, a

succession of images, and in its causes as an outer framing device of question

and answer, symmetrically.

The

inner structure sees the unopposed landing, the short ride to Rome, the

disaster of the Rangers ambushed, the construction of the Caesar Line with

minefields and heavy fortifications, the farmhouse of a forced laborer, and

snipers on the rise.

Recklessness

precedes the landing, timidity accounts for the failure,

the corruption of contact with the enemy is the essential reason for an almost

feminine submissiveness to Kesselring’s absent response.

Dmytryk’s

masterpiece was generally trounced in reviews. Vincent Canby (New York Times)

dismissed its “fatuousness”, Variety its

“banality.” Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times) saw the film and

found it praiseworthy, Tom Milne (Time Out Film Guide) has

“run-of-the-mill”.

“Threadbare”

is Halliwell’s Film Guide’s assessment, giving the Monthly

Film Bulletin on “crassly portentous statements” as well.

Shalako

It’s

a rough rhyme for calico, has a meaning in Zuni Indian, and replaces Moses

Zebulon as a convenient moniker.

Renata

Adler of the New York Times found it an agreeable Western, but sitting

as she tells us in the front row of a crowded theater, fell under the

impression that Stephen Boyd was playing an Andy Devine character, as she puts

it.

Thus the critical spectrum.

Carl

Sandburg would have loved Alexander Knox’s story of Lincoln’s first

vice-president.

Honor

Blackman goes one better than Tallulah Bankhead in Lifeboat.

Peter

van Eyck has the difficult role of a man who is always wrong and rises above

it.

Brigitte

Bardot hides behind makeup as a lady of the time, and emerges from it in two

very pretty love scenes.

Sean

Connery is a great Western star in this, and no mistake.

European

aristocrats and an American senator out West for a spot of hunting

(Dmytryk’s unforgettable studies of a mountain lion) are bamboozled by

outlaws and beset by Apaches.

Dmytryk’s

performances are typically structural, thus a reviewer cites Bogart in The

Caine Mutiny as “tired and lacking charisma” without noticing

that’s the point, Captain Queeg is battle-weary and without charm. In Shalako,

the acting is top of the line and then some, Dmytryk’s art in this

respect can be admired somewhat more freely.

But

it failed at the box office, and he disavowed it precisely as Hitchcock would

have done.

“It’s

only humiliation,” as Judy Holliday said about auditions.

Bluebeard

The proto-Nazi

baron is a World War One ace shot down by the Russians. His impotence stems not

from the injury that scarred his face and altered his beard, but from a

crippling devotion to his late mother.

The vexatiousness

of women is exposed to a mortal degree in his various brides,

he has no answer but to kill them.

A

takeoff from Hitchcock’s Psycho.

Ebert bemoaned,

incredibly, “the sad disintegration of Richard

Burton’s acting career.”

The “Human” Factor

A

front of the Cold War, NATO Southern Europe, Naples.

Friedkin picks up

a major theme for The Guardian

(deadly hired help) and a major indication for Jade (the stalled car chase through Rome).

A.H.

Weiler of the New

York Times, “improbable and gory”.

The Catholic News

Service Media Review Office pronounces the work “morally

offensive”.

Time Out,

“this movie achieves a certain bulky conviction of its own.”

The score with

its homage to Maurice Jarre is one of Morricone’s most beautiful.