Ludwig der Zweite

König von Bayern

Das Schicksal eines Menschen

Dieterle is on the spot, as it were, where Visconti

is ex

post facto.

The monument is raised to the savior of Wagner, or rather a toast.

A “streng historische”

film by intent, and without tendentiousness by design.

It is a question, says Dieterle, of understanding a personality better in this

latter day. He presents the facts, does no analyzing, lets the Ministry and the

people speak for themselves, variously, he plays the role himself for

Universal, a greatly advanced film.

Her Majesty, Love

|

|

|

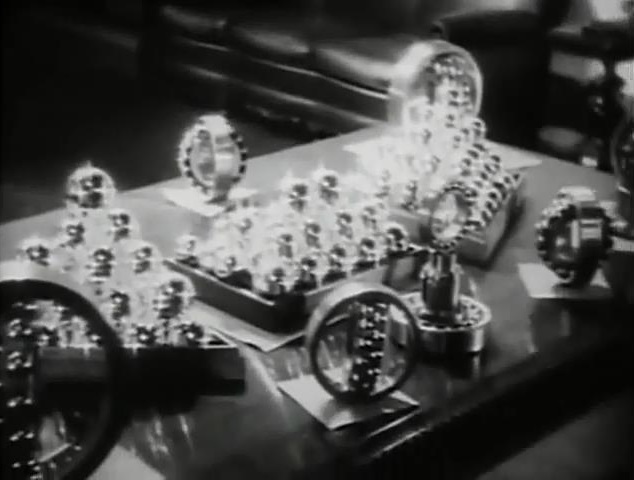

A Pinter revue sketch that opens at the Berlin Cabaret and continues in

the offices of the Von Wellingen Ball Bearing

Foundry, a family firm run by “a lot of old ladies male and female and some of

them both.”

Dieterle

in Hollywood, echt Berliner (cf. Max Ophüls’ Lachende Erben), board of directors and all that

go right into Capra’s Broadway Bill

with advantage, a musical (cf. Ophüls’ die verliebte firma.).

“Are we going to

have a directors’ meeting or—are you going to crack nuts?” Perfect

Hollywood, the style, Ben Lyon heading the cast. The directors

vote, the scion walks...

His engagement is

announced to jazz Wagner from the Cabaret orchestra. “I think you’re a little

bit tipsy, ahhh? Never mind, it’s a very good omen

for marriage, I was half stewed when I proposed to your mother.” The

father-in-law has a barber shop, was in vaudeville, W.C. Fields more than

sublime, sire of Will Geer, circus man as well, daughter tends bar at the

Cabaret, “believe me it helps,” father of Archie Rice, “you must come and see us some time.”

The firm will

meet all terms the scion proposes, so long as he doesn’t marry the girl, infra dig, the soul of virtue,

Hungarian, Marilyn Miller, sonnez la cloche,

“a real girl, and you are nothing but

a lot of—a lot of—ball bearings!”

Thus the man of sense marries her, where the sensible man signs her away, but

it’s the man out of his senses who keeps her, and she is now a baroness.

Mordaunt Hall of the New

York Times, “Wilhelm Dieterle, the director, wins top honors in Her Majesty, Love, a breezy little affair which was wafted into the

Winter Garden last night, Mr. Dieterle’s direction of The Last Flight revealed him as a stylist, but here he accomplishes

even greater wonders by his joyous manipulation of the camera.

“The scenes of this film swing swiftly along, with hardly

a pause, yet through Mr. Dieterle’s magic touch nothing is confused. He darts

here and there, blends in flashes with quick dissolves and impresses one as

being a producer who could make a poor story interesting and a good story a

masterpiece... Mr. Dieterle also shows himself to be a wizard with the

microphone and it is really astounding how he keeps his camera going from place

to place... one cannot but hope that some day Mr. Dieterle will be rewarded by

a narrative more worthy of his artistry and fertile brain.”

Variety, “Marilyn Miller and Ben Lyon doing a tango

on the cabaret dance floor... turns out to be the picture’s high point.”

Leonard Maltin, “unbearable”. Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader), “perhaps most notable for...” Time Out, “few belly laughs but much charm.” TV Guide, “a flat, inept

musical comedy”. Mark Deming (Rovi), “Fields’ juggling routine provides the high point”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “heavy-handed”,

citing Clive Hirschhorn, “exceptionally dismal”.

Jewel Robbery

The sublime technique has a cushion, Keighley as associate director.

“Untouched and in the suburbs? Oh, no! No, that doesn’t

intrigue me at all.”

The banker under another guise who purloins the

finest and bestows it on a lady of highly romantic imagination.

“Show me your jewels, will you?”

“Of course,” replies the robber.

“I hope it’s been a lesson to you.”

A.D.S. of the New York Times found that “William Dieterle’s

direction has the proper daintiness and wit,” but “Kay Francis, who can be a

good actress, is a definitely bad actress opposite Mr. Powell,” and that is

what makes horse races.

“The Warner Brothers answer to Trouble in Paradise” (Dave Kehr,

Chicago

Reader).

“Lubitsch-like bauble... breathlessly paced, witty and charming”

(Leonard Maltin).

“Imitation-Lubitsch romantic comedy” (Hal Erickson, Rovi).

“Good sparkling fun” (Halliwell’s Film Guide) “in the shadow of Trouble in Paradise.”

The Crash

A woman’s vanity and a man’s weakness make up the sum, the opposite of

these put paid to it.

Dieterle, very far advanced in technique, between Siodmak’s La Crise

est finie and Capra’s Broadway Bill.

Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times, “scarcely a stimulating piece

of work... sadly amateurish... on the surrounding program there is a Laurel and

Hardy comedy, which elicited loud laughter by the slapstick work of these two

comedians.” Variety, “a weak

picture... makes dull entertainment... an ambling narrative... ends about

where it began, at both of which points it is indefinite and in the meanwhile

it meanders vaguely... seems reasonable to look for the picture to bring

indifferent returns and go down in the records as an in-and-out... picture is a

medley of inconsistencies... audience reaction gets to the point of bored

indifference... the fadeout is a triumph of inconsistency... the surroundings

are flawless, but nothing happens in them to pique interest or capture sympathy

or even provoke hostility.”

Leonard Maltin, “plodding”.

Sandra Brennan (Rovi) could not follow the plot, “she destroys her

husband because she is bored with her lover and wants to start fresh in

Bermuda.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “dim... poor...”

6 Hours to Live

At an international trade conference, the delegate from Sylvaria is murdered to prevent his lone dissenting vote.

He is revived like a rabbit from a scientist’s hat, with reference to

Whale’s Frankenstein.

His striking speech electrifies the opening scene. “The trade policy

you suggest would wipe my country off the map. It would deliver her helpless

into the hands of those who covet her. It would mean—more idle men, starving children,

women selling their bodies for—for bread.”

Thus an adumbration not only of Sartre’s Les Jeux

sont faits (dir. Jean Delannoy) but Albee’s Everything in the Garden as well.

Annus

mirabilis,

six films that year.

Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times, “the impossible is at least made interesting”. Sandra Brennan (All Movie Guide), “off-beat sci-fi

film.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “fanciful hokum”, citing Variety, “should bring picture into the

money.”

Scarlet Dawn

Ken Russell in Dance of the Seven Veils and David Lean in Doctor Zhivago have incorporated the material

as far as possible, “out of this madhouse, this cemetery that once was Russia!”

Mamoulian’s We Live Again takes another long view, Chaplin’s

The

Immigrant

is assuredly the basis.

Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times was nothing but convinced this

was a masterpiece manqué,

“not up to Guy de Maupassant’s fine style.”

Leonard Maltin, “fairly

interesting oddity.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “heavy-going romantic drama”, citing Variety per Hall, “fails to arrive.”

Grand Slam

The author of genius versus the hack or ghost writer, the title comes

from bridge.

The genius asks, “must one use a system? Can’t one use

one’s own intelligence?”

“NO,” the other players exclaim. William Blake,

therefore. Einstein on chess was probably the inspiration,

Dieterle is just the man for the job, therefore.

And this is Stravinsky’s advice to young composers, “take a year off

and make a million dollars.”

The Stanislavsky Method of Contract Bridge is Church-endorsed and has no rules for husbands and wives to fight over, as proven in tests.

An intensely

amusing masterwork on “the modern pastime” from the Liederkranz

Club to all points west.

“America’s Bridge

Sweethearts” go bust, the ghost goes to press.

“They’ll never

think of Brooklyn, the saps.”

The Swedish

champion is a plain allusion to the literary in a film about cards (cp. Catch-22, dir. Mike Nichols).

The world stops,

time stops, everything stops as he plays the challenger at a New York hotel

(cp. Rich and Famous, dir. George

Cukor).

“I belong not to

any clubs! Clubs is for sissies, I’m a pinochle

player!”

The world and

time and everything resume when “the Bridge Sweethearts are reunited!”

Mordaunt Hall of the New

York Times sided with the overdog in a blunt and

noisy review, “blunt satire and noisy slapstick.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide has “able spoof” (and Variety, “should be enough to show a profit”).

Fashions of 1934

The essence of crime, a long joke about evading the altar in one

ludicrous scheme after another, and that’s only one

side of it, Dieterle’s masterpiece.

Golden Harvest Investment Corporation (New York, N.Y.) goes broke, what

other racket presents itself but haute

couture

knocked off from Paris?

California ostriches, a phony Russian duchess, a phony U.S. Senator and Oscar Baroque the couturier lead to the classic revelation in the City of Light that high fashion descends from the Old Masters and can therefore be forged.

Busby Berkeley

handles the stage revue called Elegance, the latest creations are

revealed behind double scrims at Maison Elegance, a progress from painting to

picture.

Variety had no idea, this was

“predicated on a false premise,” therefore. M.H. of the New York Times

allowed himself to be carried away.

Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader) speaks of “below par...

strange casting” etc. Halliwell records it as “slight”.

Fog Over

Frisco

“Why, boys, this is a New Deal, ain’t it?”

Stolen securities go West to Bello’s,

frequented by a stepdaughter of the rich and plaything of the mobs, blonde

Bette Davis meets Douglas Dumbrille there well before

My

Little Chickadee (dir. Edward F. Cline).

A root and source of Hitchcock’s Marnie (cp. a Stranger Among Us, dir. Sidney Lumet). “I have a strong hunch we haven’t

scratched the surface yet.”

Case of the missing sister...

The city is an evident inspiration, though Dieterle’s exquisite

technique is already seen before his location shooting comes into play.

“Clean your feet!”

“I didn’t step in anything.”

Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times, “what Fog Over Frisco, the new film at the Warners’ Strand, lacks in the matter of credibility, it atones for partly by its breathless pace and its abundance of action.” Leonard Maltin, “snappy melodrama”. TV Guide, “when Jean-Luc Godard named his homage to Hollywood Breathless, he must have had this film in mind.” Dave Kehr (Chicago Reader), “breathlessly paced”. Geoff Andrew (Time Out), “no masterpiece, but a fascinatingly brisk thriller”. Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide), “still manages to leave viewers breathless.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “very entertaining despite its plot inadequacy,” citing Variety, “another racketeering story,” Robert Forsythe of New Masses (where he wrote of Mae West “who so obviously represents bourgeois culture at its apex that she will enter history as a complete treatise on decay”), “the shallow content of ideas makes you want to scream,” and William K. Everson, “its speed is artificially created”.

Madame Du Barry

“Will no-one bring me a woman who knows nothing of politics?”

All parrot and lapdogs in bed. Du Barry Was a Lady, says Del Ruth. “I don’t like

the idea,” (war with England) “let’s forget it.”

Famously, she is doing to France “just what it’s doing to me.”

Reginald Owen, the more English the more French he. Dolores Del Rio

discovered by Osgood Perkins, unalterably opposed by Verree

Teasdale and Henry O’Neill, Victor Jory in opposition turned friendly, Maynard

Holmes and Anita Louise the Dauphin and Dauphiness, Marie Antoinette, “poor

little redhead,” Dieterle everywhere, one of five films he directed that year,

a chef-d’œuvre, cinematography Sol Polito, score chiefly by Mozart.

“A nice way to start a regime.”

Andre Sennwald (New York Times), “fails rather definitely to come

alive”.

Variety, “a Hollywood idea of

Versailles.”

Leonard Maltin,

“superficial”.

Hal Erickson (Rovi), “romp.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “unpersuasive”.

Just the feminine version of Ludwig der Zweite.

The Firebird

Vexations of the author, parrot-actors (the ex-wife claims her

alimony), the paterfamilias who saves his daughter

from Tolstoy’s Resurrection by burning it forthwith, and so forth, and this is Vienna.

“As for The Firebird, it’s fit only for savages.” Now you know where you are,

but a step from Friedkin’s Jade. Hindemith had to rebuke the players once for adopting such

views.

“How can anyone write under these conditions?” Stravinsky took lodgings

in a piano factory.

“He was terribly conceited, and always telling

lies.” What says the daughter? “They don’t mean to let me grow up.”

Andre Sennwald of the New York Times, “it is difficult to become

aroused”.

Hal Erickson (Rovi), “all but forgotten today.”

Dr. Socrates

End of Red Bastian and his gang in Big Bend, Oh.

The local folks is “a mite standoffish” with

the title character, a Chicago man.

“Bastian’s men have been terrorizing the middle west,” Federal agents move in.

The doctor’s

philosophy holds him in good stead.

Andre Sennwald of the New

York Times saw “a bit of minor league melodrama” and expressed his wish “that

the Warners locked up their armory for the season,” like John Leonard bidding

Norman Mailer curb his genius (Variety,

“seems a minor effort”... TV Guide,

“a most minor effort”). Leonard Maltin,

“enjoyable... offbeat”.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “good star melodrama” (citing the Sunday Times, “rapid, strong and

exciting”).

Screenplay

from W.R. Burnett, cinematography by Tony Gaudio, a rich sendup

of small town life.

Dieterle’s

signature is Dr. Ginder spilling the silver service

at the last.

Hal Erickson (Rovi) has the plot wrong, beginning with “a prominent

physician”.

Edwin Lawrence

has the comeback in Important News

with Chic Sale.

Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet is a chemical basis for the treatment of disease, Pasteur is a chemist,

the two films run parallel.

Antisepsis (childbed fever), inoculation (anthrax in sheep, rabies in

dogs and wolves and men), stolid opposition in the Academy.

He wears

himself out in this, beard and pince-nez are noted by

Ferrer in Huston’s Moulin Rouge.

A

portrait of a scientist, or as Frank S. Nugent put it

in the New York Times, “a monument to the life of a man.”

Halliwell

quotes Variety famously, “probably limited b.o.,

but a creditable prestige picture,” which recurs in Kazan’s The Last Tycoon.

Satan Met a Lady

A very beautiful and probably

unique masterpiece (B.R. Crisler in the New York

Times expressed his view that it was

“a farrago of nonsense” and a work of insanity, there’s criticism if you like)

in the Germanic style, a little like Fritz Lang’s Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse in some ways, a little like John Huston’s The

Maltese Falcon in others, from the same source.

Crooks

think Roland’s horn was crammed with Frankish gems by the Saracens to silence

it, Ted Shane of the Shane & Ames Detective Agency falls into the case when

his partner is murdered.

Many

films get up this head of comic surrealistic fervor and élan from time to time,

Dieterle sustains it throughout, continuously, and probably the source of the

joy is just how dumb crooks are (a theme common to Huston and Lang).

“An

inferior remake of The Maltese Falcon” (directed by Roy Del Ruth), Variety

thought, and so did Jonathan Rosenbaum in the Chicago Reader

(“perversely rewritten”, says Halliwell).

Tom

Milne in Time Out Film Guide came very close to appreciating its

limitless virtues.

Another Dawn

An outpost

in Mesopotamia. “Now that’s what I call a democratic orderly. Sleeps in your bed and

snores at you... Kipling should have immortalized Wilkins.”

A beautiful construction on the

theme of love and duty, the hero’s madness, “who only stand and wait.”

Korngold is justly praised by Hal Erickson (Rovi),

the rest he calls “this dreary exercise”.

Leonard Maltin, “well-paced adventure story”.

Time Out,

“flimsy fare indeed.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “absurdly sudsy melodrama.”

The Life of Emile

Zola

Dieterle’s Zola, whose peculiar

genius is to size up a situation in a trice, without reflection, and act

instantly upon it.

Cézanne

(in a striking self-portrait sat for by Vladimir Sokoloff)

is the emblem of his conscience when the Dreyfus affair is brought to his

attention as a successful author championed for the Académie

by Coppée.

Critics

at the time grasped the achievement (Time, Variety, New York

Times), so did Pare Lorentz and John Grierson, more recently critics such

as Tom Milne in Time Out Film Guide (“well-meaning pap”) and Dave Kehr in the Chicago Reader (“utterly, magisterially

bland”) have taken a different view.

Blockade

A vision of

the pastoral landscape, Spain.

“The Spring

of 1936”.

Dieterle sifts the rhetorical

position with great speed, having Ivens’ The Spanish Earth in view, and quickly arrives at

the facts of the matter.

Opposite to this are “adventure, money, love.” He has the curious pivot of a

passport photograph for this, there is an art in

obtaining a true likeness. Spain is expressly compared to a work of art, for

the benefit of one who understands such things.

Variety missed the mark by a long country mile, “a plea against war,” it said, that “pulls its punches.”

Tom Milne (Time Out), “totally spurious.”

Mark Deming (Rovi)

essentially parrots this error.

“Now there’s an example of war psychology. Of

course in my opinion this whole war is psychological.”

A work of

genius, to be sure.

The prayers

of the people.

It is all too much for a

mercenary spy, too much entirely.

Frank S. Nugent could not follow

it, nor Otis Ferguson, as cited in Halliwell’s

Film Guide, likewise (the famous notice of

impartiality is a mere blind).

The sewer, before Reed and Wajda. The observed sinking of the S.S. Fortuna is almost certainly remembered

by Fellini in Amarcord and E la nave va.

The

great score by Werner Janssen was nominated for an Oscar, also the story but

not the screenplay by John Howard Lawson (Rudolph Maté’s cinematography is “mentioned

in dispatches” but not Alexander Toluboff’s art

direction).

Hitchcock

gives the denunciation of Gallinet his raremost praise by incorporating it entire (suitably

embellished) in Foreign Correspondent.

A court-martial for the traitor, out of Beethoven’s Fidelio.

Before Hitchcock, before Chaplin, a direct appeal to “the conscience

of the world.”

Juarez

The immediate spur is the Spanish

Civil War, it animates the drama in a most cogent way

until the scene drifts back beyond the events and the American Civil War to the

American Revolution, which is where the screenwriters wanted it.

The expository dialogue

that states the drama was ignored by critics at the premiere and has hardly

fared better since. Therefore, Bette Davis and John Huston reportedly have

their jokes about Paul Muni stealing the picture with the help of his wife

(according to Davis) or his brother-in-law (according to Huston), because every

critic has remarked that Brian Aherne’s performance

overshadows Muni’s, even though that is not the case

at all.

The character of Juarez

is further explicated by Dieterle in The

Hunchback of Notre Dame. The gnomelike statesman with his democratic gnomons is a mighty

performance by Muni, even stationary in a carriage outside the headquarters of a

rebellious vice-president, most remarkably so, behind his heavy makeup and

deeply ensconced in his equipage.

Aherne gives one of the

most beautiful performances in the cinema, and when you add Davis’s Carlota

(and Claude Rains as Louis III with Gale Sondergaard

as Eugénie) you get a film easily twenty-five years

ahead of its time.

Korngold shows what he is made of at the prince’s investiture,

he raises the diapason to a level that he himself surpasses before the scene

concludes.

The triumphant vulture observed

by Carlota is the emblem of KAOS. There is an implied criticism in Maximilian’s

“manifest destiny”. The Emperor and Empress ride in a closed carriage through

Mexico like Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon and his bride. The film opens with news of

Gettysburg and ends in 1867.

Carlota’s prayer echoes Werfel’s vow at Lourdes. Bertolucci has a great use of the

material in The Last

Emperor. The Republic of Mexico

is beset by a foreign power that aims to restore the central authority, with

the Church’s blessing. An absolute monarchy extends an offer of “united

opposites” to Juarez as prime minister, he refuses in

a memorable speech.

Meissonnier

paints Louis’ portrait astride

a dummy horse. Davis’s

Carlota betrayed by France (in the face of the Monroe Doctrine) finds her voice

at a pitch much favored by Kurosawa for royalty (The Hidden Fortress, Ran). Juarez’s exploit at the human barricade reappears in Boorman’s Beyond Rangoon.

Carlota plunges into the

dark of madness like Monroe Stahr in Kazan’s The Last Tycoon. Corked wine feels the seasons of its vintage, it’s said, not of its

pouring.

The Hunchback of

Notre Dame

Variety objected

that the production “overshadows to a great extent the detailed dramatic

motivation of the Victor Hugo tale”, stepping on it, as it were.

Frank S. Nugent (New York

Times) entirely rejected it as “a bit

too coarse for our tastes now.”

Quasimodo translates his

name, “as shapeless as the man in the moon,” the moon of prayer.

Phoebus is slain by Frollo, the High Justice.

Esmeralda and Gringoire the poet depart together.

It is neither too coarse

nor too refined, for it has the nobles’ petition and

the Court of Miracles.

The King is wise and

good, as far as it goes, and so is the Archdeacon, for that matter.

Dr. Ehrlich’s

Magic Bullet

Huston or Kurosawa is the great

analyst, in Freud or The Quiet

Duel.

One of the screenwriters is Huston, Wolfgang Reinhardt is the producer of Freud as well.

Kurosawa shows the result of the disease left

untreated, in direct relation to the war.

Praises from Frank S. Nugent in the New York

Times and Variety are panegyrics, quite appropriately so for a

masterpiece of this order, add those of Halliwell’s Film Guide citing

Pare Lorentz, “a superb motion picture.”

A Dispatch from

Reuters

Dieterle’s wit runs even to hilarity,

but the gentlemen of the press did not find profundity in it, Crowther (New York Times) objecting to the service de pigeons as perhaps beneath his dignity.

Jefferson’s liking for

Newspapers even above Governments is dramatically realized even unto Aachen, where Julius Reuter is a democrat and a champion of

the free press (his wife says yes by return pigeon).

William Carlos Williams’

famous lines on the news were not yet composed, they complete the equation.

Capra took up the

pharmacist’s mistake in It’s a

Wonderful Life, Welles the poeticizing

and dilatory assistant in Citizen

Kane (he is Bensinger the poet of The

Front Page).

the devil and daniel webster

The word is Scratch, loan sharks,

the bankruptcy laws and the Grange. Critics like to see Faust in it (“Benet isn’t Goethe,” said Variety, which saw it early on as Here Is a Man, “it’s mostly symbols and morality play”), the orator’s successful

plea before “a jury of the damned” is founded on an American’s right to his own

soul, “don’t let this country go to the devil” (Tom Milne considered this “a

little portentously patriotic” in Time Out Film Guide), but it comes down only to selling your soul for a pot of Hessian

gold and the luck of the devil (“you’ll never be President,” says the Devil to Daniel

Webster, “I’ll see to that”), a fleeting proposition.

Bosley Crowther

(New York Times) thought “it should have been directed by someone who has understood

New England.”

Halliwell’s

Film Guide gives it the highest

praise (under yet another title, all that

money can buy), with reference to

Welles’ Citizen Kane from the same studio.

Tennessee Johnson

On its way to the trial in the

Senate, it passes through the inspired opening sequence that dawns on

Rosenberg’s Cool Hand Luke and Montgomery Clift (by way of Van Heflin’s

inspired performance) and Ritt’s Stanley

& Iris (Dieterle gives a short account

of Mr. Bernstein’s story in Citizen Kane from Thomas Ford).

This is closely related to the

theme of Ludwig der Zweite and the devil and daniel webster as well. It will surely be remarked how far in advance of Cukor’s Born Yesterday it appears and yet less than a

decade lies between. In the meantime there is Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and Ford’s

The Man Who Shot Liberty

Valance.

Not only Clift

but Brad Dourif, a comprehensive performance...

drawing from 1860 onwards precisely on Welles as Kane.

A loyal

Tennessean who fights for the Union. The defense of Nashville. Reconstruction.

Lincoln’s

Vice-President. The material is directly

transmuted as Kismet.

Frankenheimer has the

confrontation with Thaddeus Stevens as a crucial preparation for Seven Days in May.

“It’s like walking into Ford’s

Theatre knowing what’s going to happen,” says a gallery spectator. The

abolitionist Stevens is carried in to prosecute on the shoulders of two black

porters. Exclusion of witnesses, as in Inherit the Wind.

“The issue

of Union or Disunion.” Return to the Senate.

T.S. of the New York Times, “a fine and absorbing

biography”, he was ready to fight it over again, “may not be inspired drama.”

Leonard Maltin, “sincere... glossy”.

TV

Guide, “the

Hollywood treatment... slightly above-average”.

Halliwell could divine none of

this, citing James Agee on “Dieterle’s customary high-minded, high-polished

mélange”.

Kismet

Dieterle is ready for you on the

set of the royal palace.

How the Caliph came to marry the

daughter of the King of beggars, whose charming lies beguile a Queen in old Bagdad.

The hand of

fate, the title. “And why not?

If a king isn’t a king he’s just a yahoo!”

Inspired score by Herbert

Stothart. Songs by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg.

“My rose will bloom for some

camel boy. He’ll never know how sweet she is.”

“Eah,

guess he has been drinking too much.”

What would you have, Satyajit Ray

on a fairy tale? Colman in his element, everybody in their

element. “I wonder what this barbarian wants to have traveled so far” in

1944, to see the Grand Vizier.

P.P.K. of the New

York Times dozed off before the end, but “otherwise it is a lavishly

staged, fast-moving and generally enjoyable picture.”

Truffaut

notes the assassination attempt in La Mariée était en noir.

Dancing? “It’s the

flower on the mountaintop!” Which is precisely the point of Peter Brook’s Meetings

With Remarkable Men. It’s a fair bet that Ray saw

this before making Jalsaghar, Kurosawa before The

Hidden Fortress for his clowns.

And when the German

cinema comes to Hollywood for its life, it answers Lang’s Metropolis

with Dietrich in gold like something out of the Ballets Russes.

Stothart evokes Strauss, Wilde’s incense is brought, Russell

has Salome’s Last Dance.

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “hollow and humourless”. For the splendiferousness of this, Colman lays on a touch of

Barrymore, all in fun (but cf. Crosland’s The Beloved Rogue),

Newton as well, he practically invents O’Toole.

Lubitsch has a Bagdad like this (Sumurun), Lotte Reiniger an adventure (Die Abenteuer

des Prinzen Achmed).

The

play, arranged by John Meehan, a great and able masterpiece.

“Ridiculous, beggars

don’t disappear from Bagdad.”

Cedric

Gibbons, Charles Rosher (Technicolor), Irene and Karinska.

Whether Salome dies or

is converted is the dramatist’s coin, as one-sided as Bob le flambeur’s.

It is observed that fairy tales are all that ever truly comes to pass.

Before

the divan, the case of the woodchopper’s ass and the “overly smart barber”.

Magic, “thus

demonstrating to the All-Highest, that nothing in the world is real.” The

dramatic construction, we may well believe, proved too mystifying for the

critics.

“Rather a dead beggar in

Bagdad than a living monarch of the wilderness.”

The choral triumph just

precedes Sir William Walton’s in Henry V.

I’ll Be Seeing

You

The construction is after the

manner of a joke. Why is a woman in prison like a GI neuro-psychiatric

case? Because it’s World War II, they have each other.

Crowther (New York Times) told everyone to go and see it, “warming”, then true to his creed as

a “critic” picked several bones to look busy.

Time Out

Film Guide labels it “mainstream

melodrama”, whatever that is, and that’s what Halliwell’s Film Guide says, though Punch had the beginnings of a very dim little idea there’s more to it than

meets the eye of a critic.

The construction is

quite specific, a boss falls from a window after assaulting the girl, the

soldier with a Purple Heart and South Pacific battle ribbons lies on his bed

seeing the ceiling light descend upon him like a bomb.

It’s Christmas time and New Year’s, each is on a furlough.

Crowther vouched for the authenticity of the homey setting, Uncle’s house.

Love Letters

Here precisely is the theme of Grand Slam, a G.I. writes them for another

in Italy to a girl in England, the beau is killed, the

writer looks her up, not far from his childhood home.

The tone of the war in a

prismatic perspective, young men and women mostly, parents looking on,

carelessness and foreboding, the Italians something else again.

No-one home

at Meadow Farm, Longreach, Essex. “OFFICER MURDERED, WIFE HELD”, says the London Journal.

There is another girl...

amnesiac, at the scene of the crime.

In the second half of the film,

this one meets the writer.

Thus it opens the way Journey into Fear (dir. Norman Foster) ends, on

Joseph Cotten writing to the lady.

“Sentimental twaddle”, wrote

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times in one of his most despicable

reviews, but do not despise him, he managed on the same day to find Renoir’s The Southerner admirable.

They are one and the same, of

course, Victoria Remington and Singleton... “Canti”, she says in the Italian dub, after citing Mark 8:36, “e giardini.”

Wedding in

a bomb-damaged church (cp. Mrs. Miniver, dir. William Wyler).

The influence of Welles is

palpable and well-studied.

The kinship to Hitchcock is

particularly close.

The postman, the bridegroom’s written

hand, cause her to reflect uneasily.

The Bible she writes her name in

leads to a shiny new motorcar. “Oh, guarda la macchina! La macchina nuova!”

It takes her home, though she doesn’t remember (here the gag resemblance to the literary amnesia in LeRoy’s Random Harvest might be noted).

“Una

strana calligrafia...” A film of miraculous technique and great style.

The truth of the murder

is revealed to her mind in the Constable landscape (cp. The Paradine Case, dir. Alfred Hitchcock).

Variety just noticed

“sheer brilliance.”

Similarly Time Out

Film Guide (Tom Milne), “a really rather ravishing experience.”

On the

other hand, “oddly unexciting” in Halliwell’s Film Guide, “depressive”.

This Love of Ours

From Pirandello, two pirouettes

on a theme of caricature applied to the Occupation of France. Dieterle takes

his time, a good long time, to deliver the goods.

They come at the child’s

birthday party in the last scene. One is the mystery guest, a music student

blind before an operation, the other a rapt chess game tiresomely kibitzed.

That is all, as it used

to be said during the war. That’s enough, was the reply.

Critics (Variety, New York Times, Halliwell) did not perceive it.

Portrait of

Jennie

Portrait of Jennie is a very nervous film, with a

kind of horreur sacré at what it wishes to reveal,

namely the progress of an artist from the “winter of the mind” through the

various stages (“the bitter steps”) to nothing less than the Metropolitan

Museum of Art.

Dieterle saturates the film with themes of Debussy to achieve a

dislocation from the audience response in the critics’ minds. The critics have

a love/hate relationship with this one.

Richard Donner’s Twinky is one of many echoes. Powell

& Pressburger’s I Know Where I’m Going! is in

turn an influence.

The tidal wave sequence is answered by La Nouvelle Vague in the person of Godard (Éloge de l’Amour).

The optical effects in the lighthouse scene anticipate Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

There is no tower or refuge, only the Faun’s veil, an old scarf.

Rope of Sand

A vividly realized picture of the Union of South Africa, and thus

closely related to Losey’s The Go-Between.

T.M.P. of the New York Times refrained from making foolish

remarks and merely described it as “a robust exercise in muscular cinematic

gymnastics.” Halliwell did not contain himself and, likewise avoiding analysis, came forth with “ham-fisted adventure story which

suggests at times that a violent parody of Casablanca was intended. The stars

[Lancaster, Henreid, Rains, Lorre, Calvet, Jaffe] carry it through.”

Vulcano

The point of departure is Flaherty’s Man of Aran.

Maria lives there, Maddalena is sent back

from Naples by the police. Both are sent to Coventry.

There is an underwater crew for the swordfishing,

a documentary crew for the pumice harvesting, and the dramatic crew.

An Italian film produced and directed by Dieterle, which must be

acknowledged as an extraordinary piece of good fortune, he made three other

films that year.

Maddalena prays on her knees outside the

church she is debarred from entering, God descends to her,

there is no other way to describe it as filmed.

Question of a treasure trove aboard a sunken ship in these parts,

involuntary memory is a deep sea diver, Beckett says of Proust.

Leonard Maltin, “slowly paced dramatics”.

Hal Erickson (Rovi), who has the plot wrong,

“a standard ‘smoldering passions’ yarn.”

The lesson is sedotta e abbandonata, as the phrase is. A Vulcano girl has never been to a cinema, what’s it like?

“Dreams on canvas,” as Dali would say. Tuna fishing with nets, the tonnara, an

image of the trap (cf.

Hawks’ Tiger Shark).

By a remarkable coincidence, Rossellini’s Stromboli was made at the same time.

The Magdalen does a good deed for Mary, ahead

of Salome.

Death of a mascalzone. Fiery end of Maddalena...

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times tells us how it came to be made

and that it is “a heavy and turgid entertainment... very picturesque and

tempting... seems enacted and contrived... an artless, antique film” (he saw it

dubbed in English, as Volcano).

Paid in Full

A firm basis for Vertigo (dir. Alfred Hitchcock) in the department store

model dropped by a rich matrimonial target and landed by the man in the

advertising department loved in vain by the girl at the drawing table with a

view of the city.

Dieterle follows the line of the work himself in September Affair, here the tune is by Victor

Young and Dean Martin sings it on the restaurant jukebox, “You’re Wonderful”

(lyrics Livingston & Evans). Question of the wrong horse

for the jockey (cp. The Great Dan Patch, dir. Joseph M. Newman). The tale of Happy Sam. “Just shows you, when you think

everything’s lost, the good things are just coming your way.”

“That’s all Ben wants out of life, someone to talk to, a laugh once in

a while, and a reasonable profit.”

Death of the idol, breakdown of the idolater, “a new

nation conceived”.

New York Times, “a plodding work largely

lacking in genuine drama or conviction.” TV Guide, “a good waste of time.” Leonard Maltin, “turgid soaper”. Hal

Erickson (Rovi), “doesn’t

always play well today.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “stolid, contrived tearjerker.”

September Affair

One of the wonders of the cinema. “Forgive them, for they are

young, in love, and they are Americans.”

They see Naples and die in the Corriere, a misprint.

Rome, Naples, Pompeii, Capri... the history of Rome in the opening

sequence, L’Oro di Napoli (dir. Vittorio De Sica), the life

of Ancient Rome, the world of Capri...

A hugely concentrated style of filming, exact, on

the mark, yet at the same time very easy to suit the theme, stopping to put

Walter Huston’s record of “September Song” on the phonograph and listen to it,

the leading man of Dodsworth (dir. William Wyler).

Costumes by Edith Head, piano Leonard Pennario, two cinematographers.

“There it is, the beautiful city of

Florence...”

Robert Browning has “Parting at Morning” to resolve the thing with a

pirouette.

A terribly recondite passage has the Hitchcockian

conductor and cymbal crash at Carnegie Hall repaid in The Man Who Knew Too

Much with

the foreign agent’s resemblance to Dieterle’s Italian engineer.

The peculiar economy of the structure is similar to Another Dawn.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times was averse,

nay, a poem, “rambling drama... hopelessly silly story... simple... this banal

adventure...”

Variety paid attention and noted the plot.

The Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “slick tale... pulls out

all the emotional stops... strictly a formula affair... rings hollow.”

Leonard Maltin, “trim romance”.

Time Out notes certain aspects of the construction and refutes the charge of

emotionalism.

Hal Erickson (Rovi) could not quite follow

(“respective spouses”) but finds it “consistently good to look at, even when

the pacing flags and the dialogue becomes too

verbose.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide, “turgid”, citing Penelope

Houston, “essential superficiality.”

The war, too, her passport is from London, she hasn’t been home to the

States since 1938...

Dark City

The writing is intricate overall and fragmentary from scene to scene,

it conveys a whole biography between two poles, the clarion call of war and the

other one of peace.

“People act different when there’s a war on,” peace has its orders and

duties as well, the film is a postwar analysis of the

shift.

Ted Post’s Hang ‘em High picks up Ed Begley and

the recrimination theme with a rare understanding,

otherwise Dieterle seems to have gone unrecognized here.

The Cornell man who served in England drifts into the Chicago

underworld loosely as a card hustler, one of his colleagues rigs a game, the

victim hangs himself, vengeance comes from an older

brother. The nightclub singer belts out her lyrics in vain until the mess, not

without psychological implications on top of everything else, achieves its

result. Extricated, one has “other plans”.

Red Mountain

The man in an honorable profession who wakes up to find he’s serving

Gen. Quantrell for “a whole Western empire”.

An excellent analysis is given in The Jayhawkers! (dir. Melvin Frank).

Subtle but vertiginous camerawork shows Dieterle’s hand.

“I’m a soldier. I do what I’m told.” 1865, the war is over in the East.

“The Confederacy is dead, we have loyalties

only to the living.”

The remarkable opening shot, one of the finest in the cinema, replaces

a pair of forelegs with boots and spurs at the Assay Office in Broken Bow,

Colorado Territory.

Franz Waxman at a critical juncture is just ahead of Leonard Bernstein

in On the Waterfront.

Dieterle repeats the opening shot with a difference, four legs and a

corpse.

Quite the classic Western, for all that “it just doesn’t make much

sense,” according to Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times (Halliwell for once does not follow Crowther).

The Catholic News Service Media Review Office has “convoluted... predictable...

contrived.”

Boots Malone

The author of Salty O’Rourke (dir. Raoul Walsh) takes it

around the track again to work out the equation more analytically, further

abstracting the Runyon in the direction of Ritt’s Hud (music Elmer Bernstein), drawing

in more of Capra’s Broadway Bill (or Riding High), and with Stanley Clements once again, what gets a

good horse, a great horse even, to the finish line.

“My blood, poured down the sewer, wasted on a spoiled rich runt.”

“I’ll miss him too.”

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “hews close to a line of frank

reporting and dramatic plausibility.” Variety, “good emotional moments and

sentiment without being maudlin. This handling also is reflected in the direction

by William Dieterle.” TV Guide, “crammed with authentic racetrack lore.” Hal Erickson (Rovi), “a satisfying horse-race drama, though one might

expect a little something extra”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “dullish... bogged-down...

repetitive and unsympathetic”.

The Turning Point

The syndicate is back in a “fine midwestern

city”, it deals elegantly with a cop on the take who turns against it, he dies a hero.

An investigation brings to light a securities firm with all the records,

the syndicate smuggles them out and blows the whole building up.

A highly–placed underling brings in a torpedo from Detroit to gun down

a reporter at the fights.

By this time, investigators have the goods.

H.H.T. of the New York Times saw Kefauver in it, nevertheless “sober but uninspired” was his judgement.

Salome

A Galilean princess (Rita Hayworth), who is to be queen, a dutiful

daughter in love with a Roman commander ordered home by dint of his Christian

views, at the last one amongst the crowd to hear the Beatitudes.

Basil Sydney’s stolid military governor Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem is

an absolutely perfect portrait, so is Cedric Hardwicke’s

Tiberius Caesar. Alan Badel’s John the Baptist is the

middle term between Maurice Schwartz’s pious religious counselor Ezra and the

Messiah. Stewart Granger’s Claudius seems about to hatch from his armor, a new

creature. Charles Laughton’s Herod is played down

very quietly until he runs in fear to Ezra’s chamber after the deed is done, still its full majesty is ultimately matched by Judith

Anderson’s Herodias, infinitely cunning.

Bosley Crowther took it for a sex show in his

New

York Times

review. Halliwell’s Film Guide has “distorted biblical hokum”.

The idea is to convey, amidst a carefully refined array of provisional

models (ancient and modern, Roman and provincial, Jewish and heathen), the

sudden drastic conversion of the princess following on her brief meeting with

the prophet in his prison cell, at the sight of his head on a platter ordered

by her mother.

The King dashes off to Ezra, the Queen leaves the throne room laughing,

Claudius and Salome attend the Sermon on the Mount.

The Dance of the Seven Veils, beautifully photographed by Charles Lang,

is intended to win the Baptist’s freedom, Herodias makes a side deal first.

Elephant Walk

A psychological representation overlooked by reviewers.

“Hardly a work of art” (TIME).

Bosley Crowther dismissed it entirely in his New York

Times

review.

“Leisurely-paced romantic drama” (Variety).

Several critics (Judith Crist, Jonathan

Rosenbaum) were grateful for the stampede.

“Grade A fiction for ladies” (Halliwell’s Film Guide).

A superb cast in a work of genius.

Magic Fire

A magnificent and very able analysis of the œuvre, even in a clipped overview necessitated by studio cutting

of as much as an hour, according to report.

The life and work are seen as congruent, the latter especially vivid

for its understanding conveyed in the barest means, a minute or so of a

re-created first production each time.

The author is that of Juarez.

And so we have Dieterle’s Richard Wagner, somewhat compressed as he was in life by straitened circumstances much of the time, and thought to be a monster by some, from Rienzi to Parsifal, a great artist.

The title is

given from the Ring to signify the catalytic powers of the artist.

Halliwell’s

Film Guide finds this “remarkably

boring” and dispraises the Republic Trucolor as well

(cinematography by Ernest Haller).

The

Life, Loves and Adventures of

Omar Khayyam

He will not have a boughten slave to his

mistress but the true one that is the focal point of his existence, verses and

astronomy and calculations supply him with adventures enow

in “the time of the Assassins.”

It is hard, a hard thing, wormwood and gall, to read the vapid reviews

by Bosley Crowther in the New York Times and by Variety, and later on Halliwell’s

Film Guide.

Others noted one of the greatest films ever made and acknowledged it in

Dr.

No

straightaway.

The mystery of the hashishin, the setting forth of

an accurate calendar, the composition of poetry that made Crowther

gawk, a philosophy of life worth living, the whole

monumental gizmo went by the critics like a burp, the poet has a verse or two

for that as well.

Quick, Let’s Get Married!

The collapsed church with its statue of St. Joseph,

concealing a treasure.

The puttana knocked up whose Beppo dreams of New York on his lonesome or not, even.

A typically profound Dieterle formulation, from

Allan Scott.

The madam has a career for her, the mayor of Tolino

a thief who proposes architectural repairs gratis with half a map only,

the rest “lost somewhere in the pages of the books that haven’t been read yet

in the Vatican Library.”

Rosenberg’s Cool Hand Luke for the dialogue

with the saint (whence The Confession as a title), The Marx Brothers for

the curious structure, the canniness of small-town American life for the

Italian.

A damn defective dam is yet another image of the catastrophe. “Pia Pacelli, you’ve been greatly

blessed,” says the thief in the night to the transfigured puttana.

“Incredible! I always thought this whole thing was solid.”

“I’ve been a pretty good man, uh, at least as good as any politician

can be.”

“Have faith,” the empty saint replies, “make restitution.”

“A village redeemed,”

un peu engloutie.

TV Guide, “a completely

forgettable bomb”.

Cf. Irving Pichel’s The

Miracle of the Bells.