Terror

Island

Untold wealth

sank without a trace in the Great War, Houdini as Harry Harper proposes to

administer it via submarine to

“little waifs everywhere—like those two out there” selling

newspapers.

A

work of supreme genius.

Someone else has

an interest in the proceeds (cp. Beyond

the Poseidon Adventure, dir. Irwin Allen). Eugene

Pallette as Guy Mordaunt

double-crosses his old man Job for them, no less.

Question

of human sacrifice, a pearl “stolen from the tribe’s idol”

(cp. Haldane of the Secret Service, dir. Houdini). Faux fire reveals the gem (cf. “The Case of the Blushing Pearls” for Perry Mason, dir. Richard Whorf), but

Lila Lee makes off on horseback.

A reel or two is

missing. Compensatory sacrifice is a feature of Ludwig’s Wake of the Red Witch, see also Ustinov’s Vice Versa. Naturally all this reflects

upon King Solomon’s Mines

(dirs. Stevenson, Bennett & Marton, or Thompson).

A

thrilling demonstration by the escape artist, “world-famous for his exploits

as a self-liberator.”

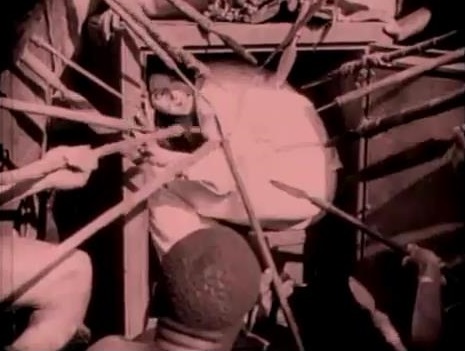

A girl locked in

a safe at spearpoint, chucked in the sea, Mordaunt has it rigged with dynamite, Harper ventures out

through his submarine’s airlock, the latest thing, and returns a few

minutes later to fend off a deep-sea diver and fetch up the diamonds. Finally

it is clear who is holding who hostage for the wealth, and that completes the

image.

“To the

superstitious natives the reappearance of their two victims rising from the sea,

is nothing short of a miracle,” the one described by Elizabeth Bishop in “Suicide

of a Moderate Dictator” with reference to contemporary events in Brazil

happily foreseen by Capra in Mr. Smith

Goes to Washington (cp. The Story of Jacob and Joseph, dir. Michael Cacoyannis).

The

Covered Wagon

The two paths,

Californy and Oregon, are later analyzed in The Wrong Road.

The plow is the

main image, reviled by hostile Indians, abandoned by gold-seekers, planted in

the snowy ground of Oregon by a pioneer.

Cruze takes upon

himself the visual manner of presentation, it is not filmed correctly (for

that, see Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail) but according to the lights

of George Catlin, an altogether different proposition.

Therefore these

are true images of the westward journey, still more, a true way of seeing.

None of these

points has ever been grasped by reviewers, who nonetheless acknowledge the

grandeur or sweep or expansiveness and some if not all of the acting.

Two reels’

worth of the original twelve has been trimmed over the years, evidently, and

the prairie fire is nowhere to be seen.

The Great Gabbo

“Averroes’

Search”, one of the Ficciones Borges wrote later, is certainly a

key to this film and to the inability of critics from its premiere until the

present to have any idea why, for example, it contains musical numbers (which

appear well-known to Russell and Powell & Pressburger in The Boy Friend

and The Tales of Hoffmann). No wonder these Multicolor sequences are

nowadays rendered in black-and-white, though half the picture is expressed by

them in fulsome terms, the Broadway show as pagan love ritual and just the

thing Eliot was looking for in The Rite of Spring.

Opposed to this,

the other half of the picture, the Greek drama and its second actor,

represented by the ventriloquist Gabbo and his dummy Otto.

The game is

played quite gentlemanly, Broadway gets a full revue advantageously filmed

onstage, “350 people” tap and sing, the ballet is nonpareil, while

the Great Gabbo gets the Stroheim treatment in his act. The picture is signed

by Ben Hecht in the story department, he of the subtlest mind in pictures.

I Cover the Waterfront

One of those

newspaper reporters (two actually), drawn from life, who write bunk and bilge

for a living but very occasionally trace down a good story.

Three top

reviewers couldn’t see it for beans, Graham Greene did best, Variety

ran a poor second, Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times deplores “one

of those newspaper geniuses to be found only in motion pictures”.

Tony Richardson

absorbed it for The Border, Fritz Lang echoed it in Clash by Night.

The peculiar

notes of the West Coast probably caught critics unaware.

The smuggling

trade, a Chink in the drink, a Spanish prison hulk with torture implements

(Lyon and Colbert take the 25¢ tour memorably), the great shark hunt, a Chinese

coat for the lady, the exposé, no more back to Vermont or on to Singapore.

A great film

pitiably disregarded. “Somebody’s got to do the

washing.”

The Wrong Road

The advantage of

stealing is you don’t have to work, you have a lot more right away than

if you worked for it, a prison sentence is your way of earning it, that’s

all.

So reason the young

couple not long out of college, he (Richard Cromwell) should have been a

well-paid engineer by now, she (Helen Mack) a member of society.

A detective from

the bonding company (Lionel Atwill) gets them paroled after two years of ten,

the money they’ve purloined is still in her music box but Uncle

Bill’s Antique Shop is closed, the thing auctioned, a fellow ex-convict

wants the dough, they can’t get married until their parole ends.

It just

isn’t worth it, they finally resolve, and give back the money from the

bank where he was a teller put on two-weeks’ notice so a relative could

be hired, that sort of establishment.

The crime is laid

out in the droll opening scene at a swanky nightspot, Club Cubanola.