King Kong

The wildest Irish

hypothesis sets this in the accidental poetry range in response to Howard

Hawks’ Scarface

like Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde,

the extraordinary patient craftsmanship not to the contrary, and one is not

referring to O’Brien’s art with its Laoco÷n touches and perfection of mimesis. The Oscar-nominated photography is only surpassed and set

off by the editing, which itself might give rise to Hitchcock’s

definition of cinema as “a succession of images”,

furthermore a process shot of a falling apartment-dweller lingered with him for

a quarter-century.

Everyone knows

what Whitmanesque means, but none or few notice the meticulous construction of

his poems. Poetically, Kong is allied to Emma

Lazarus’s “New Colossus” (in fact, they turn out to be

united), technically, the complete calm of the image stream identifies the

careful preparation of each scene in the script. One

might mention Schaffner’s The War

Lord as thematically related.

Odd to think so

rare a beauty sprang up a short walk from the present city, at RKO Studios, in

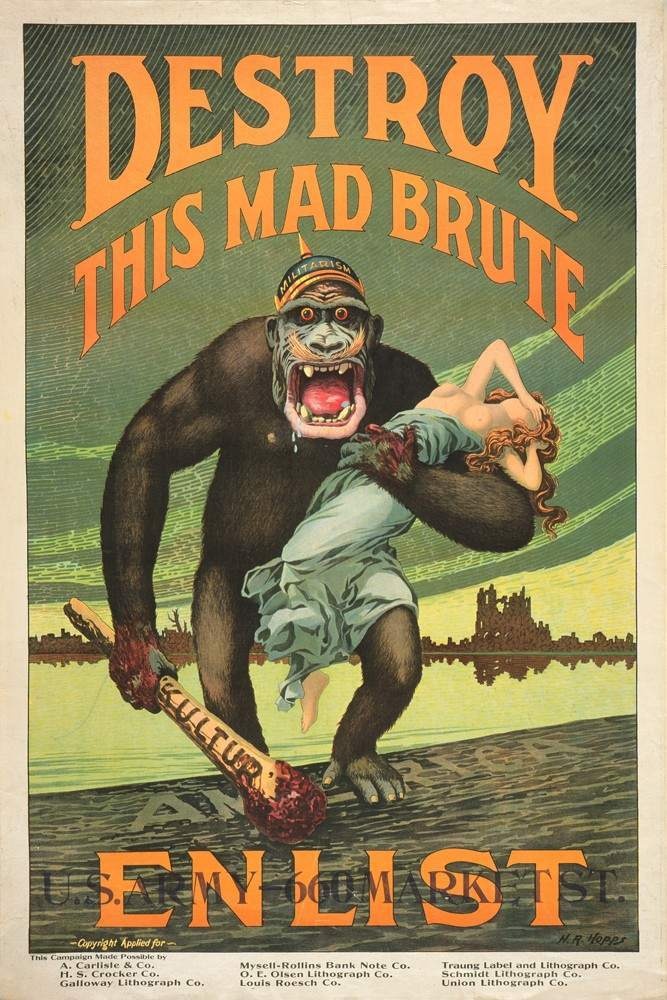

the very year of Hitler’s accession to power. Harry

R. Hopps’ World War I recruitment poster for

the U.S. Army (Destroy This Mad

Brute—Enlist) bears a likeness of Kaiser Wilhelm II, Edward the Seventh’s nephew Willy

(dir. John Gorrie), as the Ape of Militarism that

tells all the tale (Hopps is one of the artists responsible

for Raoul Walsh’s The Thief of

Baghdad).

Mordaunt Hall of the New

York Times, “a fantastic film”. Joe

Bigelow (Variety), “highly imaginative and

super-goofy yarn is mostly about a 50-foot ape who goes for a five-foot blonde.” Time

Out, “all the contradictory erotic, ecstatic, destructive, pathetic and cathartic

buried impulses of ‘civilised’ man.” Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “this classic adventure fantasy succeeds

largely because of the giant ape’s sympathetic treatment and Willis H.

O’Brien’s imaginative special effects in animating Kong and the

prehistoric world of Skull Island.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “the greatest monster movie of

all,” citing more of Variety,

“should gather good grosses in a walk,” also James Agate (Sunday Times), “just amusing

nonsense”.

The Last Days of Pompeii

The village

smithy is obliged by the State to fight in the arena for gold, believing it to

be omnipotent.

His son espouses

the slave religion Christianity.

Charlton Heston

in Robson’s Earthquake but

echoes Preston Foster’s disconsolate walk among the fleeing crowds as

fire rains down upon the town and harbor.

Andre Sennwald of the New

York Times, “a shade too long for complete comfort.”

Variety, “what is

presented is a behind-the-scenes of Roman politics and commerce, both of which

are shown as smeared with corruption and intrigue.” Leonard

Maltin, “climactic spectacle scenes are

thrilling and expertly done.” Time Out, “Mt Vesuvius blows its

top in fine fashion somewhere near the end of this sword-and-sandal

spectacular, but all the molten lava the special effects team can cook up

isn’t enough to atone for a cool, dreary script.”

TV Guide, “does not

quite come off, but it remains entertaining.”