Bataille du rail

After the introductory material, the film opens on a sight that

instantly identifies it with the European and the Scandinavian position, a sign

forbidding Jews to enter the occupied zone.

From that point,

the Maquis have their allies among the railwaymen of

Frankenheimer’s The Train, who

risk their lives to impede the Germans at every turn.

Furthermore, it

is a question of communications across the two zones set up by the Germans,

transporting men and mail in secret.

After D-Day (le débarquement),

operations are intensified to prevent reinforcements arriving in Normandy.

On stolen

bicycles and horse-drawn wagons, on foot (and with a last stab at utilizing the

rails), the Germans depart France one and all.

The magnificence

of the resources placed at Clément’s command is no less surprising than

the ease of his mastery, he has all the German soldiers and equipment needed,

trains, tanks, cannon, even an armored train that goes over the side at full

speed.

Le Père tranquille

The chef du groupe in Moissan is a colonel who sells insurance, assurances,

and in his spare time grows notable orchids.

The influence of Wyler’s Mrs. Miniver seems evident, if

possible, and the germ of an idea for Jeux interdits also.

The magnificent technique displayed, indeed lavished effortlessly on

this masterpiece, is pure Clément.

Time Out Film

Guide’s

remark, “overall it’s too tendentious to take seriously,” is

one of the most astounding constructions ever foisted on a work of art.

Le Chateau de Verre

The love of a Switzeress and a Parisian, met

by the sea in Italy.

Paris, “c’est

pas une grande ville,” he tells her in a taxi, “c’est beaucoup de petites

villes.” Cf. Dearden’s The

Bells Go Down.

A hotel in the Palais-Royal, even if the

proprietress says so the elevator doesn’t work.

“An imitation of rigor and elegance,” thought Truffaut.

She’s married to a judge with a most amusing case, the points of

reference are Anna Karenina and Brief Encounter, he’s a traveling salesman...

View from the Pantheon. Score Baudrier, conductor Jolivet. Cinematography Le Febvre. Novel the incomparable Vicky Baum.

Ahead of Monsieur Ripois, Clément dans les rues. Litvak

has Goodbye Again, a remote memory.

Dr. Roman Colbert was asked by a student to explain je vous aime and je t’aime, “before and after,” he said,

thus the Palais-Royal, “now I recognize

it.”

The title is a souvenir d’enfance.

Jean Marais, whose specialty is the tour de force, Michèle Morgan.

Godard and Rivette arrive at the Gare de l’Est.

Jeux interdits

A complete, devastating satire of France in 1940, top-to-bottom, all

the way around. It couldn’t be more absolute if

Daumier had drawn it.

For half a century, it was misunderstood as a childhood sob story or

tract, effectively damning Clément’s subsequent work.

Only John Osborne in England has the same cry of rage tempered by humor

of the best sort on a total disaster.

Monsieur Ripois

It leaves the London office et voilà the New Wave, as Rimbaud

would say.

English girls, Truffaut had his nose in the book and missed them,

crossly, but made l’homme qui aimait les femmes (and, to be sure, Deux

Anglaises et le continent), cf.

Edwards’ The Man Who Loved Women.

Godard might have taken his inspiration from the rainy rendezvous with

Norah for Adieu au langage (Flicker perhaps

remembers it at the end of The Troublemaker, to say nothing of Gilbert

likewise for Alfie).

And does not Schlesinger in Midnight Cowboy remember

Clément’s Hyde Park? The citation from

Wyler’s Carrie is just rounded off to fit nicely, and in this

scene amongst the prostituées one recognizes

Ophuls’ La Ronde, which is what Dali

would say is quite a pirouette (Malle has the “Prince de Galles” in Atlantic City).

The “heteroclite” library of Cadet-Chenonceaux

has Touchez pas au grisbi,

among other things (Queneau’s Le Journal intime de Sally Mara).

Lovers, Happy

Lovers,

“an odd and interesting film” (Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times).

Time Out does not go so far as

to suggest Losey’s The Romantic Englishwoman, but only just.

Mallarmé’s Swan appears in his own right as well as the

poet’s (the critic John Simon is said to have done his thesis on “Hérodiade”), “son pur

éclat...”

“A little Waterloo never killed anyone,” but observe how

close the hero comes, after several arduous and disagreeable conquests, to

winning the fair.

Bresson famously emulates his end in Une

Femme douce, “il

s’immobilise...”

According to Truffaut, “Hémon’s Ripois was a monster, Clément’s is a cynical

buffoon,” for Crowther the latter was

“the lowest form of human heel”, even

worse than Pal Joey.

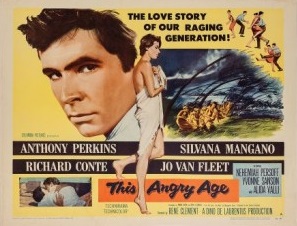

This

Angry Age

How ya gonna keep ‘em

down on the farm after they’ve seen Bangkok?

A firm called Legros makes a bid on the

place, Legros fils

for the daughter.

The son makes bold to leave, the sea wall breaks, a lover is stranded, he recommends concrete.

A lady whose paramour drinks and falls asleep at the cinema, not

“following the affair” (an American crime drama, Yankee culture gets

a ribbing).

The lover is a disgraced merchant mariner, blamed for a shipwreck.

The brother returns home, the man of the house. The

sister departs for Portugal with the lover, construction work.

Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles and Les Enfants terribles (dir. Jean-Pierre

Melville) figure visibly in the

composition.

The typhoon is rather like John Ford’s Hurricane,

Clément’s greatest effect is simply an impromptu lunch on the river.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times,

“there is considerable truth in this film, if you

care to look for it.” Leonard Maltin,

“ludicrous mishmash”. TV

Guide, “to no avail”. Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “moments of interest and even beauty.”

Plein soleil

The title means “full sunlight”, though in English it is

heightened as Purple Noon, and suggests among other things George

Stevens’ A Place in the Sun. The plot developments

more closely resemble Richard III, Olivier’s film is certainly a

memory of the war. These are the steps by which the

level of thought in Clément’s film is comprehensively obtained.

His remarkable steadiness of nerve has been noted, along with a

resemblance to Clouzot in Les Diaboliques on that account,

relieved by a kind of diabolical humor.

Everything has been hammered out to beaten gold,

the sense of refinement is a long clear look in the light of day.

Quelle joie de vivre

Clément has seen and admired Joannon’s Utopia

with Laurel and Hardy, evidently.

It gives him a basis on which to examine anarchists (“libre totalement volontairement solitairement libre”) and blackshirts

strictly from hunger in Rome at the start of the Twenties (cf. Bolognini’s Libera,

amore mio... ).

“Qu’est-ce que

c’est que la liberté, hein?”

“Mais la liberté

c’est, euh, pas aller en prison.”

“C’est lamentable.”

Le Trou Sylvestre, from Becker. The exquisitely refined technique serves in a comic mêlée

and at the setting of the anarchist bombs as well. Ulysses

the Spanish graveyard and his exploding cauliflower. The

magic lantern show from Shoeshine (dir. Vittorio

De Sica). The title song in a Roman ristorante (“Che

gioia vivere”). The arrival of the generals from the Four Powers.

Fascist tools at the Foire de la Paix ahead of Dearden’s The Assassination

Bureau and Friedkin’s Deal of the Century (cf. Gilliat’s Left Right and Centre for the

structure overall).

Homage to Piranesi.

The

Day and the Hour

Occupied France. “The war doesn’t

interest me.”

“Aren’t you interested in the fact that we’re defending

you against Communists, plutocrats and the Jews?”

“No.”

Two slaps. “And that—that interest

you?”

Cf. Asquith’s The

Yellow Rolls-Royce. “Who is to be the big

hero, you or me?” The “Swede, lives in Montparnasse, a painter, he had a show in New York,”

is of course Max von Sydow in Hannah and Her

Sisters (dir. Woody Allen). Bombed in Paris

playing Louis’ blues (Au Revoir les enfants, dir. Malle), drunk as James Dean. Losey has Mr. Klein, Rossellini a certain General Della Rovere, Clément “the famous Sophie” in the

hands of the French police who want one Titus (cf. Cassavetes’ Gloria,

or Lumet’s). “In the Gestapo they have the

latest scientific methods.” Partisans, O.S.S.,

Spain, D-Day.

Howard Thompson of the New York Times, who found the romance not

to his liking just as a predecessor of his objected to Dassin’s Reunion

in France, “reflects the visual wizardry

of the director.” Hal Erickson (Rovi)

speaks of “fellow undergrounders” and

does the lady a disservice.

Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema (“his two best

films—Lovers, Happy Lovers and This Angry Age—were

both English-language productions”) makes a point of not admiring it (Is

Paris Burning? he calls “disastrous dullness”), with Signoret

and Whitman in the dub.

Joy House

Like The Big Sleep, a marriage fantasy, but not a film noir,

though the flashlight scene is a joke on this.

The structure is punctuated with hallucinatory jokes, a cast-iron key

ninety years old and big as your forearm down a lady’s front for

safekeeping without a blink, an infuriated motorist on two wheels who lands on

all four and remonstrates, the woods are full of them.

An affair with a gangster’s moll, then on the lam at Villefranche-sur-Mer with a widow and her lover and her

cousin in a mansion “neo-Gothic”.

A close precedent for Altman’s That Cold Day in the Park. “Dismal claptrap,” said Howard Thompson (New

York Times), “pure, pretentious baloney,” a close precedent for

John Simon’s review of the Altman.

Is Paris Burning?

“My God. Gentlemen, you have heard which way the wind’s

blowing.” The great division in the main factions of the

Resistance is dealt with briskly, Catholic Youth meet Young Communists in a

Gestapo trap. The screenplay is thus most economical,

and yet lavish in its beauty and precision. “Brad,”

says Kirk Douglas as Gen. Patton just apprised of events there, “what the

hell’s going on in Paris?” He’s on a

field phone to Gen. Bradley, a brave Resistance fighter has traveled to the

Normandy front with news, crossed the lines and been led to Patton in his tent

(Douglas evokes Patton without mimicry, an heir of Grant).

The city is mined on Hitler’s personal order. The German officer who receives this order knows the

Führer is mad, nevertheless the charges are laid. Resnais’

Von Choltitz figures in On Connait la Chanson. The

example given in a German newsreel is Warsaw, “it was here that the

Polish terrorists first fired on German troops... a lesson not only to the

Poles, but to the world... Warsaw no longer exists,

and it will never exist again.”

Orson Welles appears as Swedish consul Nordling

in the film’s great set-piece on the Occupation regime.

It plays from the Hotel Meurice by Dantean degrees to the train platform for Buchenwald,

ending with a Daumier tracking shot in the rain.

Belmondo takes the Matignon by force

of character, Cassel storms the Meurice where Fröbe dallies, Montand fights a

tank duel on the Place de la Concorde, and so forth. There

were cameramen in Paris, they shot footage Clément

makes use of.

The title (Paris brûle-t-il?)

is asked in German (Brennt Paris?) over

the telephone from Rastenburg or Berlin in an effort

to determine whether or not Hitler’s orders are being carried out, while

bells are pealing and the lights come back on.

It stands to reason that such a history would require an

extraordinary film for its depiction, and it stands equally that the critics

were utterly unable to receive it.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times could not follow it at

all, “it leaves one exhausted and irked... do you wonder you’re

likely to burn?” Time Out, “has scarcely improved with age.”

TV Guide, “a fairly

entertaining, action-packed film which seems continually in danger of

collapsing under the weight of its own pageantry.” Hal

Erickson (All Movie Guide),

“seems more weighted down than weighty.” Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“muddled, scribbled, tedious and confusing attempt at a thinking

man’s all-star war epic.”

Le Passager de la pluie

Clément now, naturally, looks at France resisting, twenty years

after Jeux interdits

and ten after Plein soleil. She is hard to find, hard to discern, hard to explain.

But there she is in all her glory à la Mrs. Miniver,

raped, revenged, plucked out of an angry whorehouse, restored to home and

hearth.

All Movie Guide has it “confounding the audience at

every turn,” Time Out Film Guide adds “glossy direction from

Clément” as a consolation.

Tony Mastroianni of the Cleveland Press, who always sits

on his hands, brought them up to applaud Rider on the Rain “like

the Hitchcock films of yesteryear,” to be sure, “not the recent

Hitchcock.”

La

Maison sous les arbres

A very celebrated journey by barge canal (L’Atalante, dir. Jean Vigo). Que diable allait-elle faire dans cette galère?

After Le Passager de la pluie, the

question is how or why. One is not rich but well-off, dealing in images,

probability and statistics, wife has a psychiatrist and a memory problem...

A considerable light is thrown on Furie’s The Naked Runner.

Clément throws everything into consideration, but everything,

properly. The result from its first frames is one of

the great works of the cinema.

The offer, when it comes, is after the manner suggested by

Becker in Touchez pas au grisbi,

a contract... The

Deadly Trap. The pivotal image is from Ken Russell

on Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in

the World. The works of Jean-Pierre Melville may profitably be consulted. Tout simple, Resnais presents the job offer in Vous n’avez encore rien vu, from Mon oncle

d’Amérique. Americans in Paris, later on it’s Frantic (dir. Roman Polanski)...

M. le Commissaire asks dispassionately

if she has thoughts of suicide. Forbidden

Games in a simultaneous perspective, as it were. Consequences naturally for

La Baby Sitter... and in the present

instance from Thérèse Desqueyroux

(dir. Georges Franju).

If you like, a simple case of kidnapping for industrial

espionage, though Vincent Canby of the New

York Times had doubts, “all of it is so arbitrarily muddled you begin

to believe the film means to demonstrate other things... nothing really works, though.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide is the very definition of arbitrary muddling, “smoothly

made thriller which spends rather too much time being chic.”