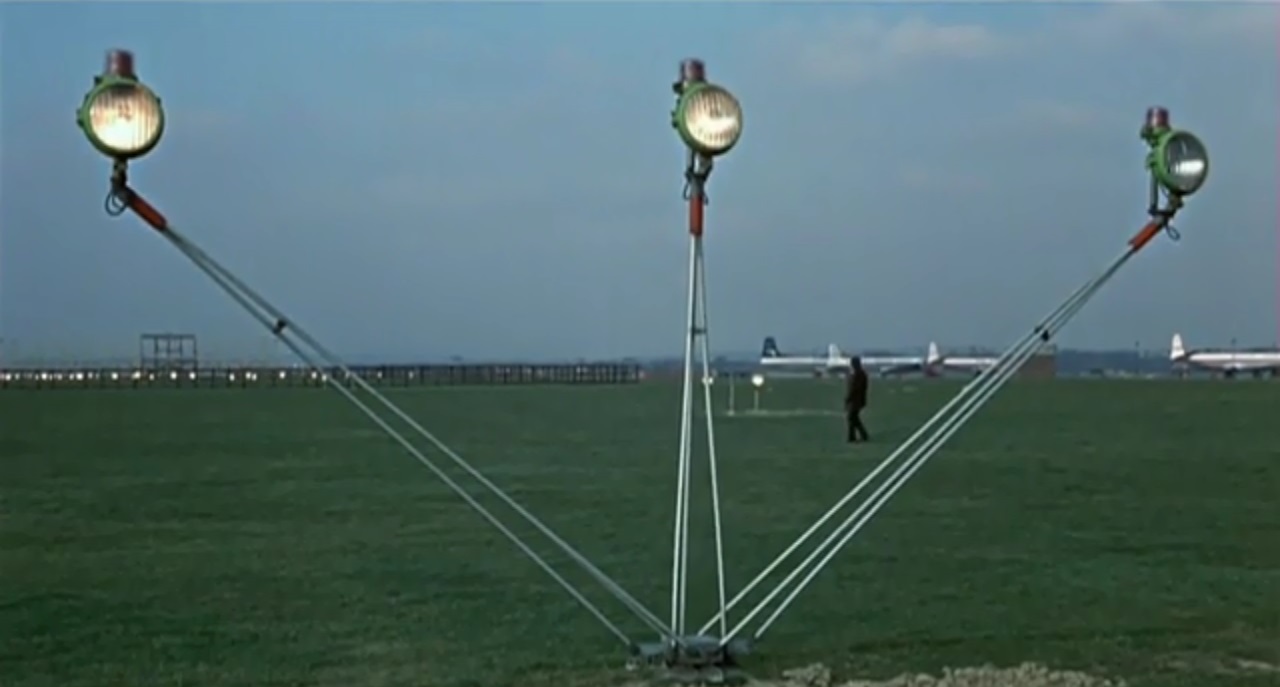

otley

Out and back off

the Portobello Road (“you’ve gotta be

careful with this Persian stuff, most of it’s made in Paris”) one

raw February by way of the spy service inadvertently, the man with the Man Ray

shave in beautiful cinematography by Austin Dempster

(editor Richard Best), like James Joyce wondering if the photographer were good

for a fiver. A particularly brilliant view of The 39 Steps, in that vein entirely unnoticed by Vincent Canby of

the New York Times who pronounced

heavily upon it, and by Time Out Film

Guide somewhat more lenient. Hitchcock thanks Clement, a hugely resourceful

and thoroughly capable and remarkably fluent director to say the least, in Frenzy. The fatal shot through a coffee

pot is by way of Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, the

empty railway station from Walter Forde’s The

Ghost Train with Arthur Askey,

and there follows quite naturally Val Guest’s The Runaway Bus with Frankie Howerd,

not to mention the peripatetic harp of Charles Frend’s

A Run for Your Money, which turns up outside the Playboy Club (the lad

with the ray gun, “pishoo, pishoo”,

is again by way of The Trouble with Harry). The saga of a skiver

in the toils of espionage and murder involving “one of those bent civil

servants”, if the cowboy in command is an Indian chief one has

“homeless bones” (cf. Amiel’s The Man

Who Knew Too Little).

So Gerald Arthur

Otley leaves the Trad (No. 67, Clement is a genius at

signs and posters throughout the film, his many jokes and asides are thematic,

the entire construction and each scene as well) for the Thames like Gully

Jimson before him, a regular Billy Fisher in London, as Canby did notice after

all or very nearly. Philip Proudfoot (“a bit

Baghdad Hilton for my taste”) of I.C.S. World News Organisation

(“London-Chicago-Tokyo”) is right out of Brooks’ The

Producers, a higher-up in the hostile force and a “great

fairy”, a bloody great London poofter in the

latest with a hulking henchman rather out of it (“he’s got a thing

against youth”) who vets for him. “Now hang on, that’s a bit

primitive. By the time you realize I know nothing, I’ll have taken a

hammering. You’re a sophisticated sort of a villain, wh-wh-wh-what

about the drugs, the truth things, the old pentothal then? Have a go at me

psyche, leave me body alone!” The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain

gave it the award for comedy. “How is

your wife?”

“Oh,

she’s still the same sweet gin-sodden bitch that she always was.”

Otley escapes when an I.C.S. underling (“I’m their assassin”)

on the mystery tours (“d’you know

we’re offering 14 days in the Dolomites for 36 guineas?”) is hoist

with a petard, he has himself arrested (North By Northwest) and is

recruited for a large sum. It’s all a question

of official bumf for sale and loyalties in doubt, it ends with the investiture

of a knight at Buckingham Palace, observed from beyond the pale by Otley, whose

services are no longer required (“the night was coming” says

Beckett, “in which no Murphy could work”). He isn’t even

worth the trouble of killing. “Generally pretty funny,” says Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “but not entirely certain of its own motives,”

stating the critics’ confusion.

Dan Pavlides (All Movie

Guide), who has our Gerry a “British secret service agent called in

to investigate”, finds it “confusing”. Thus Variety, “in seeking to avoid

overheroics as well as the pitfalls of parody, the film has an uneasy lack of a

point of view and fails to focus viewer’s attention on any particular

character or plotline philosophy.”

Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “gets lost in its own

intrigues”. Film4,

“very hit and miss.” Britmovie, “uneven”. TV Guide, “spotty”.

The critical

quandary went unabated even after the magnificent central scene in which Miles,

whose name is Rollo (“Miles is head of M.I.5,

isn’t he, that’s what M stands for”), explains everything

very patiently, which gives you an idea of the quandary. “God

you’re a charmless lot,” Otley exclaims, “how do you trust

each other?”

Or to put it

another way, “they’ll never believe this in the pub,” kicked

out of bed by the Irish landlady, have a go with a smashing bird at a health

farm in the country (cf. George

Pollock’s Kill or Cure with

Terry-Thomas), back in town find digs amid the corpses of blackmailer,

murderer, traitor, “you know.”

A

Severed Head

In which it is

made manifest that from Lubitsch (The

Marriage Circle) one arrives at the films

britanniques of Resnais by way of Clement.

Again six figures,

husband-analyst-brother and wife-mistress-bint, mathematical permutations like

a slot machine paying off variously, with cross-relationships en route that are of great interest. The vintner and the love interest, the trick cyclist and

the bit on the side, sculptor and wife, these define the proper relationships

as understood by the authoress, not as the world sees them (the middle ground

or no-man’s-land has married man and artsy bit, artist and design teacher

at the Royal College, therapist and neurotic ball-and-chain).

The critics

notwithstanding, Shelley explains the title platonically, “a poet is indeed

a thing ethereally light, winged, and sacred, nor can he compose anything worth

calling poetry until he becomes inspired and as it were mad; or whilst any reason

remains in him.”

Screenplay Murdoch-Priestley-Raphael,

décor Richard Macdonald & John Clark, costumes Sue Yelland,

cinematography Austin Dempster, score Stanley Myers.

Bosley Crowther of the New

York Times, “plodding, faithful, doggedly unimaginative... I have rarely experienced such desolation”. Variety, “intellectually

snobbish”. TV

Guide, “sexual escapades of the upper crust”.

Catholic News Service Media Review Office, “purports to be a

sophisticated comedy of manners”. Clarke

Fountain (All Movie Guide), “sophisticated

black comedy sex romp”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “tolerably sophisticated for

those who don’t know the original.”

Catch Me a Spy

The Soviets

launch one of their British operatives toward a French schoolteacher living

with her uncle, the shadow foreign secretary, in London. There is a wedding,

the honeymoon in Bucharest is interrupted by secret police, the bridegroom is

arrested and flown to Moscow. He is to be exchanged

for a spy caught by the British.

That is one-half

the story, the rest became the critics’

nightmare in its real and seeming complexity.

There is another

agent, a courier really, smuggling book manuscripts out of Russia, he becomes entangled with the wife.

This is the

height of comedy, going back to Clarence Brown’s Flesh and the Devil at one point, with Sacha Pitoeff

and a joke from Alain Resnais setting up The

39 Steps at an empty hotel in Scotland, a parody of Terence Young’s From Russia with Love on a lake between

the two Germanies, Tom Courtenay as a filing clerk

sent into the field, the Cold War one winter.

Marlene Jobert, Kirk Douglas and Trevor Howard, with Richard

Pearson as the head of British Intelligence, “no-one’s supposed to

know that.”

To Variety, “a straightforward spy

thriller” with humor. Time Out Film

Guide did not wish “to imply that anyone might care.”

Water

A superb complex

analysis of modern affairs that covers all bases from regional poverty to a

rock concert at the United Nations, “designer water” and oil and

everything else.

Brenda Vaccaro’s performance as the island governor’s

wife deserved an Oscar and was vilified by Variety and the New York

Times.

Beneath all the

bullshit, Clement wants to say (with a devastating satire of Margaret

Thatcher), there is something worth something.