Restrictions on production and distribution imposed

by the Office of Price Administration governing certain materials vital for the

war effort are flouted by a Midwest combine of “chiselers, saboteurs and

traitors” selling beef.

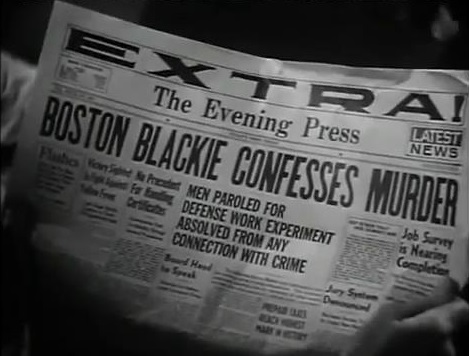

The Chance of a Lifetime

The rare, obscure mystery of a wartime dilemma

later examined by Asquith (Libel) and

Hutton (Kelly’s Heroes). “Who,” as

Huston asks in The Life and Times of

Judge Roy Bean, “did the killin’?” Question of able convicts for war work, “released

into the custody of Boston Blackie”, set to take the rap for one in a murder

case.

“Are you proud of being a fugitive from a brain?”

Castle’s first feature, typically profound and

masterful.

Leonard Maltin,

“proficient”.

The royal carpet, the dumb waiter, the lever of

love, “the two most efficient scrubwomen in our fair city...”

“I’ll bet you haven’t got that insured.”

“No sir, ain’t had

it long enough, ha-ha.”

Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “a loyal following.”

“You’re going down to headquarters and tell Farraday exactly how Red Taggart was killed.”

“In your ivory hat I will... we’re on a fast

express, Blackie, and the next stop is your apartment.” The man with the gun.

“Why don’t you go hide in a doughnut.” The tables turned. “Arthur, you’re like

the United States Marines.”

The Whistler

Murder for hire, 1944. Masterfully remade as The End (dir. Burt Reynolds). “Studies in Necrophobia

(Exaggerated Fear of Death) by Ira B. Franklin, M. D., Ph.

D.”, an assassin’s reading. “Did you hear someone whistling?”

“I didn’t notice.”

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “Columbia’s little nosegay... weary, illogical

imitation”. Leonard Maltin, “tense and moody”.

The rough-shadow, “hard on the nerves” (cf. “The Hitch-Hiker”, dir. Alvin Ganzer

for The Twilight Zone). “Yeahhh... maybe I’m on the track o’ sump’n

big, sump’n

noo inna art o’ moida. No fusss, no musss, huh. Yeahhh...”

“Suppose he doesn’t drop dead?”

“My gun won’t be empty.” Cp. Guest in the House (dir. John Brahm), The Passage (dir. J. Lee Thompson). The

killer in Bed 13. “Rats in this place as big as beavers. They won’t hurtcha, but you’re liable to trip over ‘em in the dark.” On the docks, cf. Litvak’s Out of the Fog,

amongst other things.

Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “a fairly workmanlike series of second features”.

Betrayed

“Formerly known as When Strangers Marry”. In

America, no-one is a stranger.

For ten cents, Hugo the Mental Marvel identifies

the pianist-stenographer-nurse and the reporter-lawyer-works in a bank, or does

he? “Better acted and better directed” than Double Indemnity (dir. Billy

Wilder) or Laura (dir. Otto

Preminger), according to Orson Welles in his newspaper column. Touch

of Evil remembers Mrs. Baxter at the hotel,

numerous tints of mysterious fear are transposed into The Stranger.

James Agee said it encouraged him as only William

Castle could, and “the Val Lewton contingent”.

Castle’s study of Hitchcock is quite thorough, from

the engine-scream of The 39 Steps to the tone maintained in Shadow of

a doubt, with a mainstay of Foreign Correspondent in the push that

doesn’t come to shove and the man who is not what he seems.

Agee certainly could not resist the opening on the

King of the Jungle at the Hotel Philadelphia bar, later there’s a Harlem café

where the champ is escorted after a bout.

Hitchcock richly repays in Frenzy. End of a

king in Philadelphia, partial expropriation of his wherewithal, sent to Atlanta

from the Hotel Sherwin, New York City (Grantsville, Ohio and Grant’s Tomb both

figure in this). Or, a mortal attack for which the wrong party is suspected, a

further attempt on the wartime bride.

Voice of the Whistler

“A tale of loneliness and greed,” with reference in

this latter day to Welles (Citizen Kane)

and Capra (It’s a Wonderful Life) and

Sirk (Slightly French).

TV Guide, “despite a good

idea and the proper atmosphere, the story is not brought to the screen

effectively, making for tough going as the plot drags itself out.”

Mysterious Intruder

The Whistler relates a monstrous parody of The Maltese Falcon that pertains to The

Swedish Nightingale.

A very brilliant concoction, very much in the vein

of film noir. The private dick is

Richard Dix posing for his private-eye portrait with one eye under his hat,

presented by Barton MacLane as Detective Taggart to

the woman behind the counter.

A notable précis of the Blindfold theme (dir. Philip Dunne).

The Crime Doctor’s Gamble

Dr, Ordway in Paris to give lectures on detecting

the sociopath in custody and take in the nightlife, especially apache dancing

and knife throwing at Le Coq Rouge. A case of patricide in hand at the

Prefecture, young writer out of a concentration camp and a mental clinic, “his

wife is the knife-thrower’s daughter” disapproved of by the wealthy murder

victim and painted by a rival for her affections. A criminal defense undertaken

by the victim’s lawyer.

“You are an American, are you not?”

“That’s right, yes.”

“Then you will understand, for many years I paint

originals and I starve, now I paint copies and I eat!”

The original, its detractors and apes.

The war is a recent memory. “Paris without its

visitors is like an oasis without water,” no tourists.

Texas, Brooklyn

& Heaven

In Texas, you’re on the Fort Worth desk of the Dallas

News, nothing happens.

You (Guy Madison) go to New York to write your

play, no-one reads it, a producer’s kid nixes anything

that doesn’t stink of success in his view.

Brooklyn has a riding academy (run by Michael

Chekhov) of stuffed beasts that rock before a sliding diorama backdrop. This is

a bright idea to entertain the Cheever sisters (Margaret Hamilton, Moyna

MacGill, Irene Ryan), grim old maids.

And there is the pickpocket who becomes your mother

(Florence Bates).

On the other hand, the girl (Diana Lynn) you give a

lift to in Texas returns with you to the Golden Horse Ranch.

An incomparable tale told by a New York bartender

(James Dunn) to a customer (Jesse White) over four house specials, the last

one’s free.

Lionel Stander is the indolent bellhop at the Grand

National Hotel in New York, a fleabag where the only phones are in the bar, to

encourage the clientele.

Johnny Stool

Pigeon

The West Coast drug trade (San Francisco), headed

in Vancouver (Canada), worked out of Mexico by way of

Nogales and Tucson.

The sheer elaborateness of this is answered by a

Treasury agent gone undercover with the title character, a gangster in Alcatraz

persuaded like Holly Martins with the dead in the trade.

Undertow

Out of the war, out of the racket, set up for a

murder, a pawn in a syndicate takeover.

Classic film noir material, treated fairly

and squarely, the theme however being that of Texas, Brooklyn and Heaven

(the locations are Reno and Chicago, the desideratum is a small resort outside

Reno, the Mile High Lodge, a fishing retreat).

The girl he left behind him is a kingpin’s niece, no crumb in the business shall marry her. Uncle’s

dead, the frame’s a perfect fit, there’s a friend on the force and a girl met

innocently at a crooked crap table on a schoolteachers’ jaunt, she flies back

to Chicago with helpful winnings, a second meeting (cp. The Lady Pays Off, dir. Douglas Sirk).

Halliwell found it “not at all memorable.”

It’s a Small

World

A film in three parts, The Boy, The Woman, The

Circus.

At its center are Dickens’ Oliver Twist (dir. David Lean) and Todd Browning’s Freaks. It nevertheless ends blissfully

under the big top, “getting smaller each day”, according to the title number.

Et Ô ces voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole!

Screenplay by the director and Otto Schreiber,

cinematography Karl Struss, score Karl Hajos.

Leonard Maltin,

“unnecessarily nasty”. TV Guide,

“off-beat”. Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide),

“obviously designed as an exploitationer.”

The Fat Man

There is no civilization west of the Hudson,

nothing but frying pans. Castle’s film is an elaborate statement of this fact.

As such, it is a work of pure genius, hardly

noticeable at the time (although an anonymous reviewer in the New York Times, a fan of the radio

series, liked it well enough).

Without Brad Runyon, gourmet and private detective,

there would be no Jackie Gleason, Pat McCormick, or Frank Cannon.

Hollywood Story

The town behind the credits. Kazan has the studio

tour in The Last Tycoon. Death of the

silent film director at unknown hands, New York producer looks into it, “good

story here.”

The disused studio looks like Chaplin’s.

“How green was my moneyman.”

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, “the story itself is a

bust.” Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide), “holds no surprises”. TV Guide, “could have been a much better

film”. Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“adequate potboiler”.

Serpent of the Nile

The Loves of Cleopatra

“Caesar was an old man, he

wanted a woman of luxury. Antony is young, he wants

the luxury of a woman.” Julie Newmar’s gilded dance not only goes into Goldfinger (dir. Guy Hamilton) but The Magic Christian (dir. Joseph

McGrath) as well, with its lady centurions cracking the whip against slave

girls hauling the great treasure before Mark Antony, Cleopatra, and General Lucilius, at their wine in Tarsus on the river Cydrus. This superb spectacle, under the musical

supervision of Mischa Bakaleinikoff,

evokes the golden dancer in Dieterle’s Kismet

evoking the Ballets Russes, and in one swift turning

kick Picasso’s Salome.

Nicely-judged casting splits the Roman mind between

Lundigan and Burr, republic and empire, Philippi ongoing (the battle is

represented with characteristically adroit stuntwork

and Castle’s mastery of motion in cinematic increments, the walk taken by Lucilius past soldiers to the tent of Cassius, for example,

creating a sense of its stages). The legendary wealth of Egypt is expropriated

from a starving people to buy Rome for the son of Caesar and Cleopatra.

Leonard Maltin, “good for

a few laughs, anyway.” Hal Erickson (Rovi), “quickie

retelling”.

The honorary general in Alexandria, “so was the

Rome of Julius Caesar.”

Egypt is a reed that cannot be leaned upon,

“veneer... nothing, a shell,” Antony’s hope. Unsleeping virtue perseveres

against the fatal gyp.

Bear wrestling, a sport for Alexandria’s court.

“Get out, get out, GET OUT,” shrieks Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. The Biblical

parallel has Lucilius under house arrest walk past

the drugged guards at his portal (Lundigan and Ansara have a dandy fight with

spear and short sword and shield).

“She’ll do to Rome what she’s done to you,” again

from Dieterle (Madame Du

Barry), in reverse, disguising the general reference to Roy Del Ruth’s Du Barry Was a Lady. Where Caesar fell, a

declaration of war.

A basket of figs fills the screen, an asp emerges.

Antony makes peace for Cleopatra with his sword in vain,

she finds no forgiveness with Lucilius but takes the

asp to her bosom (Rhonda Fleming).

Conquest of

Cochise

He makes war on the Mexicanos, the Gadsden Purchase

puts an end to all that.

The spectacular filming in Technicolor has been

noted by several writers, though not the fine stuntwork.

A great study or evocation of Apache culture and

customs.

The highly complex, intricate and detailed

screenplay is certainly typical of Castle’s middle period.

Halliwell’s Film Guide simply has

“feeble western cheapie.”

Slaves of Babylon

After the fall of Jerusalem (cf. Nicholas Ray’s King of

Kings), the star worn under Nebuchadnezzar, father of brutal Belshazzar.

The shepherd Cyrus, a help to Israel...

A prefigurement of DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. “The wisdom of Daniel...” the den of lions. An

eclipse remembered in Ben-Hur (dir. William

Wyler). The fiery furnace, “it dazzles my eyes!”

The princess Panthea (“she

is said to be the fairest woman in Asia”), beloved of Cyrus, betrothed to

Belshazzar.

“To Nahum, traveling slowly with Panthea in the wake of Cyrus’s army, the fall of Babylon

could not arrive too soon.”

“Tell me about your people.”

“There are so many stories!” Nebuchadnezzar eating

grass... “Great king,” this addressed to Belshazzar, “Cyrus approaches with a

vast army, and our army is not ready.”

“I am

ready.” The high walls of the city, per D.W. Griffith (Intolerance). “Babylon will live forever under the protection of

the all-powerful god Bel-Marduk!...

I’ll put their god to a real test,” a

second exodus against the siege.

The writing on the wall. A film remembered in King

Vidor’s Solomon and Sheba as well as

Henry Koster’s The Story of Ruth and

John Huston’s The Bible: In the

Beginning... (the rainbow of the conclusion).

TV Guide, “depends upon too much dialog, and Castle directs in his

usual way.” Hal Erickson (All

Movie Guide), “another ‘instant epic.’”

Battle of Rogue River

“Well, I never heard of a war where neither side

was the aggressor.”

“It’s no secret, Wyatt, that there are men who

oppose statehood for Oregon. Wouldn’t it serve their interest to prolong

hostilities?”

So Heyes’ screenplay, one of the very fastest ever

composed, dispenses its wisdom in coin before the battle, after many a lightning

turn and loop that Castle, firm disciple of Ford (proper genius his own sphere)

films with the greatest interest astride, as it were, a furiously bucking

bronco.

It is, in all the bright confusion, the Flaubert

position, successfully adopted and commended by Richard Brooks (Take the High Ground!), Joseph Losey (Figures in a Landscape), and Peter Yates

(Murphy’s War).

Castle adds a Matisse portrait of Martha Hyer to situate her in fauve

country. As always, impressive and beautiful stuntwork

is a sine qua non.

Trial by combat ends the hostilities, the two

champions or litigants are a U.S. Cavalry major and a lying thieving weasel

“under the cannon”, as it were.

Leonard Maltin, “lopsided

Western”. TV Guide, “another of Katzman’s cheapies.” Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide), “B-plus western”. Catholic News Service Media

Review Office, “Western clunker”.

Masterson of Kansas

A kind of Poe poem on the vanishing red man and

dying Doc Holliday as viewed by the title character and Wyatt Earp, for whom he

is not a bitter despairing outlaw with a Parthian shaft for Dodge City (cf. Boetticher’s Seminole).

Screenplay by Douglas Heyes.

“I’m offering you a business proposition, Doc, and

all you’re giving me is words.”

“Perhaps those words are beyond your

comprehension.”

Leonard Maltin, “just

standard.” TV Guide, “slight script”.

Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide) sees

“Doc Holliday as a borderline psychotic with a death wish.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “two-bit”.

The Americano

The point is to throw a perspective onto the South

American scene, and have one in return (A.W. of the New York Times

considered this unnecessary and redundant, whatever the cost).

Tom Milne of Time Out Film Guide says

Boetticher directed in Brazil and was replaced by Castle, he also says the

result is “ponderously dreary”.

The title character sells three Brahma bulls to a

ranch in the Mato Grosso and has to take sides in a range war of cattlemen vs.

nesters, this is highly revealing about a democratic neighbor, if you like, and

of course puts the Western (any Western, on this theme) under the microscope,

as it were.

The Gun that Won the West

“This new rifle, as you know, was developed at the

United States Armory at Springfield. It’s a .50 cal. centerfire model, weighs nine

pounds and it takes an 18-inch bayonet. After firing, this two-click tumbler

extractor will throw the empty cartridge clear of the weapon. The ease of

loading and extracting cartridges makes this the most practical breechloader

yet manufactured. The weapon is of extremely high velocity, thereby making it

ideally suited to long-range Plains warfare. This weapon can fire so far that

it can cut down the enemy before he can get close enough to fire at you.

There’s no more powerful rifle in existence. This will be demonstrated for you

now.”

Leonard Maltin,

“harmless”. TV Guide did not

recognize Wellman’s Buffalo Bill,

“consequently, there are a lot of mismatched tints between shots and unmatching grains,” the Altman theme is very rich, as are

the astute representations of the Sioux in their villages, at their rituals,

and riding on the warpath, from Catlin. Hal Erickson

(All Movie Guide), “inexpensive”.

Question of averting a war, the Wild West is a

profitable show back East that keeps a former scout in liquor, the reality

along the Bozeman Trail is Red Cloud. “Did ye ever think much about the

future?”

“Yeah, I did once.” Siegel’s Dirty Harry remembers the lecture-demonstration.

The Houston Story

A clever operator works out a scheme to tap Texas

oil production, sells it to the Houston mob (run by a St. Louis boss), the

“combine” has seen its profits fall, this is an

opportunity to recoup millions.

There’s even a pipeline to be laid for the mob’s

ships, against the cost of trucking.

The Houston boss goes back to Capone, they “detest

violence” in St. Louis, unless necessary.

A brilliant film, at the Derrick Café the operator

is nearly rubbed out and, wounded, sees the police arrive, behind him on the

wall is a sign for a house specialty, “Frank and Stein”.

Prices go up under the regime of the mobsters,

astonishingly. “Tell ‘em to raise the taxes,” says the operator to a foreign

buyer who balks, “that’ll take care of me fine.”

Macabre

The striking form “now goes mainly backward” to

reveal the basis of understanding in a succession of crimes to a single end

that one is bidden as a member of the audience not to reveal (cf. Mervyn LeRoy’s

The Bad Seed). A major theme of

Castle’s later masterworks is here announced from Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques, “fear itself”,

precipitated by a shock anticipating Hitchcock’s Psycho against an increasingly morbid, melancholy and macabre

stylistic treatment, cp. Dante’s Inferno

(dir. Ken Russell) for the exhumation, The

Terminal Man (dir. Mike Hodges) for the gunplay in the cemetery.

Tom Milne (Time

Out), “rather laborious”. Leonard Maltin, “delivers little.” Craig Butler (All Movie Guide), “an average affair.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “unsuccessful”, citing

the Monthly Film Bulletin,

“ineffective”.

House on Haunted

Hill

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House above Hollywood,

rundown with bars on all the windows and said to be the domain of ghosts, cp. The Old Dark House and Let’s Kill Uncle.

A millionaire’s wife gives a party with five

invited guests (the two can’t agree whose idea it is, even, the “loaded”

champagne bottle he points at her is by way of Hitchcock’s Notorious), he’ll pay a fortune to any who survive the night locked

in. “We’ve done it. The perfect crime. Beautiful.”

The theme of fear continued from Macabre, and another of varied murders

expressively taken up in succeeding films, cp. Strait-Jacket for example. Subsidiary motifs include the love of

money or the bondage thereof, and something akin to Bluebeard’s Castle (dir. Michael Powell) at times reflected in the

score.

Howard Thompson of the New York Times, “a stale spook concoction”. Variety, “the characters are interesting and not outlandish, so

there is some basis in reality.” Leonard Maltin,

“campy”. Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago

Reader), “the best of the campy horror films that made his reputation.” TV Guide, “good fun.” Film4, “has a genuinely creepy

atmosphere”. Alan Jones (Radio Times),

“silly spookiness... directorial crassness...” Catholic News Service Media

Review Office, “tangled plot is full of holes.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “outlandish”.

The Tingler

The objectification of fear itself as a large

spinal earwig quelled by an outcry and set loose in a silent movie theater,

where the proprietress is deaf and dumb and thus perishes (spooked by the

husband she’s at fatal odds with), and it’s this theater gone suddenly dark,

where the film is Tol’able David but concerns an autopsy surgeon

(Vincent Price) for the state with a criminal execution in the electric chair,

and his unfaithful wife (Patricia Cutts) who is bored with his laboratory

studies of fear, she keeps her sister (Pamela Lincoln) from inheriting so the

poor girl can’t marry the surgeon’s assistant (Darryl Hickman) and make “the

same mistake I did”, cf. Sekely’s Lady in the

Death House.

13 Ghosts

The incisive wit of the screenplay sets up a

question amid the skeletons of a past age at the Los Angeles County Museum’s

Paleontology Department, assembled to show the remains of birds and animals not

seen in forty thousand years (here, the critics went out for a snack).

The solution fits right in with Beckett’s reading,

|

comme si c’était d’hier se

rappeler le mammouth le dinothérium… les périodes glaciares… la grande chaleur… …et oublier son père …de quoi il est mort on n’en est pas moins mangé… |

Homicidal

The Shakespearean

tale is of a girl raised as a boy to win an inheritance. Disguised atop her

mannish persona as a Danish girl, she kills a justice of the peace and an old

nurse in a wheelchair, witnesses to the deception.

To accomplish the

first murder, she checks into the Hotel Ventura and marries a bellhop, using

the name of her rival in Solvang, Miriam Webster, a half-sister.

If ever there was

a genius in Ventura, it was Castle.

Mr. Sardonicus

His rictus

mirrors his father’s corpse, the treatment is the

father alive to him still. The side effect is an inability to eat.

Castle’s very

funny satire on problems of faith is close to Huston’s Wise Blood yet filmed in the Universal style. He pauses at the end

to poll the audience like a Roman emperor for the fait accompli of a silent mocker.

Zotz!

Borges’ magic

coin and a few of his other tricks serve the turn of Castle’s masterpiece, with

its very accurate rendition of a college language department and a main

rivalry.

Professor Jones

(Ancient Eastern Languages) is played by Tom Poston somewhere between Van

Johnson and Nicol Williamson. The very literate screenplay has him one of ten

men in the world who can decipher a five-thousand-year-old coin, whereupon he

is endowed with certain powers that mainly serve to highlight a position, a

colleague’s bluster, an enemy’s attack, and with a finger he can incapacitate a

foe.

The cocktail

party scene with white mice and Margaret Dumont is only the warmup. Jim Backus

is the rival (Modern European Languages), Cecil Kellaway the dean, Julia Meade

a new colleague, Zeme North the niece and so blessedly on.

13 Frightened Girls

Diplomats’

daughters at a girls’ school in Switzerland.

That is precisely

the way to describe the conduct of contemporary nations.

U.S. spy Candy

Hull, age 16, code name Kitten.

Her adversary is

a Red Chinese assassin, code name Spider.

All this is off

her own bat, to save the career of a special attaché whose outmoded specialty

is nowadays “done by machinery,” as he observes.

A superb film,

really grand, noticed by Cassavetes in Gloria and Cukor in Rich and

Famous.

55 Days at

Peking (dir. Nicholas Ray) or Spartacus

(dir. Stanley Kubrick) answers the attack on Miss Pittford’s Academy.

A film so

little-known, and that little so badly misunderstood, it would be well to

consult the experts, but alas, Bosley Crowther gave it the back of his hand in

the New York Times along with films by Richard Rush, Samuel Fuller, and

Paul Wendkos.

The Old Dark House

Femm Hall, a truly

decayed manor house at Dartmoor, flying from its tower the letter F on a field

of white.

The offspring of

Morgan Femm the pirate gather each night at midnight according to his will,

also an American cousin.

No more truly

exasperating critic, not even John Simon, can ever have existed than Bosley

Crowther, who on Halloween of 1963 panned this film in the New York Times

along with De Sica’s The Condemned of Altona, Resnais’ Muriel,

Shavelson’s A New Kind of Love, Carreras’ Maniac, and Annakin’s Crooks Anonymous,

though the last he said had a “droll finish”, and to be fair, he blamed The

Old Dark House on J.B. Priestley.

Strait-Jacket

Castle’s

masterpiece of virtuosity is assigned to a screenplay by the author of Psycho.

Crimes of passion and madness and murder have a serene philosophical outlook

thrust upon them, men and women are so many porkers and hens for the slaughter,

anyhow.

But you can

discern the story of one swinging lady who chops the heads off her husband and

his paramour, and goes to an asylum, and is guardedly released twenty years

later only to be framed by her daughter for more axe murders in a plot for

money.

The identity of

the killer can be guessed fairly soon, but the motive is kept for the end, with

a stinging epilogue in which the lady packs up the daughter’s amateur

sculptures (“one of those galleries on the coast”) forever.

The Night Walker

The dreamer, who

sees her husband’s stick and the whites of his eyes, and another man, and

another man, her husband explodes, leaving a hole in the floor of the

laboratory upstairs, she returns to her beauty salon (driving past Magoffin

Typographers on Yucca Street) and marries again, her husband again, another

man, another man, her husband, so the nightmare goes, a dream lover who might

be real or an alter ego of the blind staring husband scarred by the explosion,

or his attorney, or a private dick married to a girl in a beauty salon, a

church full of dummies, abandoned, an apartment rendezvous, vacated, all gone

through the hole in the floor of the empty house.

Bosley Crowther

called it “eerie nonsense... totally unbelievable... a creaky gimcrack chiller”

(New York Times).

I Saw What You Did

Castle has but

the one great joke like a porcupine up against a fox, so he luxuriates in

Hitchcock studies. Wiederhorn in Eyes of a Stranger profits from his Psycho

variant with its bursted shower door.

The opening

sequence comprising half the film is a parody of George Roy Hill’s The World

of Henry Orient so charming, accurate and well-contrived that the New

York Times reviewer was ravished out of his senses, proclaiming wildly that

Castle had no business deviating from it in the rest of the film.

The triple

goddess has her wiles but old and young she meets her match, avatars beyond a

certain point are however protected by statute.

There is a very

precise rendering of an image from “Good-Bye, George” (dir. Robert Stevens) on The

Alfred Hitchcock Hour (body in trunk in station wagon), after the next-door

neighbor’s spying eyes from “Nothing Ever Happens in Linvale”

(dir. Herschel Daugherty). The trunk gets buried among leaves beside the road

in woods, the snooping dog is there from Welles’ The

Stranger and T.S. Eliot.

Let’s Kill Uncle

A millionaire

industrialist’s son, lately orphaned in what looks like an accident, is sent to

live with his uncle on Serenity Island, once a prosperous tourist resort but

now teeming all around with sharks.

The hotel is an

abandoned wreck, the uncle lays out the ground rules under which he intends to

kill the boy, for the inheritance.

A very precise

construction, point by point identifying a very exact nightmare.

It stunned the

anonymous reviewers of the New York Times and TIME into

semi-consciousness, which is half the battle.

The Busy Body

A million dollars

in a blue suit, or what’s a nice Jewish boy like you

doing in a mob like this? Hitchcock’s The

Trouble with Harry. “Boss, Boss, when you—when you bury a corpse, you gotta do it in real style, i-if

you read Esquire you’d know it.”

Recipe for a Scotch Sour à la Norton.

“Being a widow is a—a very traumatic experience.”

“Bar syrup.”

“I went to the

mortuary to discuss the upkeep of my husband’s grave.”

“Cracked ice.”

“And seeing Mr.

Merriwether dead, I—I suddenly became irrational.”

“Lemon juice.”

“For a moment I—I

confused him with my dear husband. Uh, not too much lemon, please. You

understand?”

“Yeah, not too

much lemon.”

“No, no, I mean

about my husband.”

“Oh, well, under

stress, uh, certain people do certain things that they wouldn’t ordinarily do.”

“Ah, you’re so profound.”

“Shake

vigorously.” Cp. Dante’s Inferno

(dir. Ken Russell).

New York Times, “freewheeling if obvious scramble that blithely thumbs its nose at justice”. TV Guide,

“managed to inject a few laughs”. Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “unfunny... laboured... in poor

taste.”

The Spirit Is Willing

The most

brilliant of all comedies, and much too good for anyone to understand without

appreciating late works as a genre of sorts, unique in that everything the

artist knows is in them, refined or magnified.

It starts (in

1898) like Strait-Jacket, only the husband with a meat cleaver in his

back completes the fatal triangle (13 Ghosts).

The haunted house

gets a vacation rental that finally sorts everything out, and if that isn’t

genius, nothing is.

A continually

funny comedy with a unique sense of pace, Castle at his most profound,

far-reaching and inimitable.

The identification

of a ghostly pact with life achieves a great analysis of the earlier film.

Uncle George (“head of E-Z Flush”) falls for the lonely virgin, which frees the

husband and wife like the man and maid of yore, and their son is redeemed by

the poltergeist as well.

Project X

A spy mission to

Sinoasia, early in the twenty-second century.

The agent, a

brilliant geneticist and historian of the twentieth-century’s Fifties and

Sixties, is brought back scrubbed and dead, his mind a blank, having broadcast

the imminent destruction of the West.

His frozen body

is revived, an elaborate apparatus is employed to recover his memory, a false

past is given him to secure his participation, he is a bank robber on the lam

in 1968.

A colleague on

the assignment tries to break him out.

The feudalistic

Sinoese (who are mass-producing male infants, ahead of the West) have a secret

weapon, medieval plagues eradicated in the West like every other disease.

Treason,

deception, and a remarkable foreglimpse of Russell’s Altered States are

part of the fabric reaching far back into the silents and the serials, partly

by grace of Hanna-Barbera in animation sequences depicting action à la

Méliès.

In the end, our

man is yet another person entirely, an engineer three-days-married to a girl from

the kineries (where dairy products are processed into pills).

Shanks

Castle was never

able to make himself properly understood as a film director of genius but for a

time he labored to make his pictures seen anyway, and this was a public service

unless it be acknowledged that the Emergo skeleton of

House on Haunted Hill, for example,

adds zest to the flouting of public superstition as well as a sendup of studio

publicity angles.

The appalling

reviews his last film received were crowned by Jay Cocks’ assertion that

Marceau was a “gimmick”, preparing Castle’s epitaph.

The pure

distillate of Castle’s genius is seen for two-thirds of the picture, then he

characteristically outdoes himself.

The agonizingly

pleasurable luxuriance of the puppeteer’s revenge on his cruel relatives

finally is obtruded upon by “the outside world of evil... the dead fight the

living... good versus evil,” and the mime, taking Castle’s part as impresario,

lets you know it’s all a show.