Underground

A film wot is bleedin’ London,

Chaplin was a bleedin’ Londoner, it shows. Des Esseintes can just stay home

in Paree and watch this on the Champs-Élysées,

that’s all. A late start at the peak of the

silents, as far ahead in the cinema as it is possible to imagine nonetheless. In that regard, much like Sternberg’s The Salvation Hunters.

The wrong speed is like the wrong aspect ratio, a funhouse mirror.

The same romantic

situation as in French without Tears

(Kate loves Bert loves Nell loves Bill). Cute kid,

Nell, recites the day’s events in pantomime to her mother, the

film’s first two reels in half a minute. Sublime

girl, parrying Bert in Thistle Grove, riding atop a charabanc

with Bill, whence Minnelli has the lovers in The Clock. A day in the country as placid

as Antonioni’s Blowup. The cinema has to be invented, as for Sternberg. In this lies all the pleasure and joy of the thing. An Englishman in a canoe (French without Tears) is an ancient Briton, an urchin from town

playing his harmonica amongst the trees and fields is a rustic swain piping, the camera simply records this.

The “ruddy

melodrama” Mordaunt Hall (New York

Times) complains of is, of course, just what interests Asquith. The beauty of the construction is to complete the Lubitsch

circle by having Bill attack Kate in a factitious attempted rape set up by Bert

to disgust Nell, it happens just apart from the river of life in an Underground

station. So Bert of the Power House scuppers Bill the

Underground porter for Nell the shopgirl with a tale

of unwanted love foisted on Kate the dressmaker. A pennywhistler bemuses tykes on a London street. Hall evidently saw Bruckman’s

The Battle of the Century “on

the same program,” all he said was “more pies are thrown than in

any ten Mack Sennett productions,” Laurel and Hardy are not mentioned,

“another nice mess”. Nell

gets the drappie on the little bint, a cute kid herself who wants marriage with

Bert something awful. And there is murder in it and a

rooftop fight and finally that crane as if from Sternberg.

The function is to show the genius of the place,

attended by Fortune who is blind On

Approval, according to the well-apportioned gag, The Vagabond King.

According to Juliet Jacques of New Statesman (“a freelance journalist and writer who covers

gender, sexuality, literature, film, art and football,” and who

chronicled her sex change operation in the Guardian),

“a sincere, touching document of its time” (but this is described

as “exploring counter-culture in the arts,” etc.).

A Cottage on Dartmoor

The title

humorously gives a pithy description of a passionate love. Asquith

is of the opinion that the cinema ought to be able to express such things or

why bother?

Emotional states,

psychological states, a Mannerist heroine, the great study of a motion picture

audience (Hitchcock takes notice of one not watching the show), Dearden

capitalizes on this in The Smallest Show

on Earth, the Powell & Pressburger weather eye is there from the very

start.

“Crude...

immature” (Halliwell’s Film

Guide), from which total misapprehension other critics have refrained.

Moscow Nights

Known in America

as I Stand Condemned. History is made...

An uncommonly

influential or prescient film, with consequences far and wide.

Doctor Zhivago, Alexander Nevsky, The Queen Of Spades,

Great Catherine, Fahrenheit 451, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington

and The Bounty all owe something or other to it (it owes a little to A

Farewell to Arms and King Vidor and Les Misérables).

What Asquith

brought back from Hollywood was such a vision of Hollywood lighting as

Hollywood hardly understood. He uses it for sculpture

in relief and in the round, and if he reaches Vermeer at one point, it’s

by an understanding of light and space. Within this

overall framework and with these objects, his camera moves in constant

composition.

French without Tears

The girl is

American-bred, and so the mystery deepens, how this became Losey’s Accident by pure analysis. “Hitlaire!”, eyes to

heaven, Prof. Maingot. Months

before the invasion. Love’s Labour’s Lost upon the English gentleman (cf. Cukor’s Sylvia Scarlett, for that matter Lang’s Man Hunt), he gets the nudge, in a manner of speaking. Asquith has the joke,

“aspects” of French, Tati’s facteur finds rondeur to slap and tickle.

After Pygmalion, and Channel Incident. Quite like Sylvia Miles

in this part, Ellen Drew. Bernard Knowles director of

photography, Jack Hildyard cameraman, David Lean editor, De Grunwald and

Dalrymple screenplay, Mario Zampi producer.

Graham Greene at

this time was given to making outlandish statements on the cinema, Halliwell’s Film Guide cites him

in cold blood while itself commenting merely, “pleasant”.

Let another

English gentleman test the waters, “all right, Diana, I’d do

anything for you, even act as a sort of thermometer.” One

stands corrected, “we call her a ship in the Navy,” one’s

boat.

B.R. Crisler of the New

York Times, “may be set down as easily the most lachrymose comedy of

the season,” in which access of wit he went on to pan Laurel and Hardy in

Saps at Sea (“lacks comic

invention”) and Boris Karloff in The

Man with Nine Lives (“movie medicos are at best a strange

breed”). Time

Out, “simply a historical curiosity.”

As they say,

“nothing like discipline,” to which the reply is, “nothing.” The charming title song is not given a credit. The girl has ideas above her gare. The

height of elegance is a legible signature (Cocteau). The

human voice on a telephone in French, as natural as you please. Infinitely witty, which is why you have Ray Milland, Guy

Middleton and Roland Culver dispensing it. “If

he tries to give you the impression that I’m a scheming wrecker of

men’s lives, you needn’t necessarily believe him.”

The memorable

fracas over an India rubber concludes with a hand and arm reaching between two

hands and arms to seize it (David Tree). It never

fails, the more brilliant the film, the duller the critics. Give

them a crock and they expound like Diogenes, Archimedes even.

And it is a literary theme, question of a rejected novel (cf. Lang’s House by the River). The Foreign Office

and the Admiralty are not un œuf-f-f. John Simon

famously thought Losey’s film not all it was cracked up to be.

The one about the

two conchies in Central Africa. The play is good, the

play is great, the film is something else again. When

they make a better film, you may be sure the British Film Institute will do its

level best to inform the public. A film to put

Lubitsch on the floor in stitches. “Don’t

tread on any escargots.”

“I loved

her for her character! Did you?”

“Certainly not.”

“En français,

in French, gentlemen, toujours en

français. Vive la France! Vive la

France!”

“Officers

in the Royal Navy never pass out.”

“I suppose

they just fall on the floor in an alcoholic stupor.”

“Exactly.”

“Tell us why

we disliked you so much?”

“All right. Because, you all

made up your minds to dislike me, before I ever came into the house. All except Diana, that is to say.”

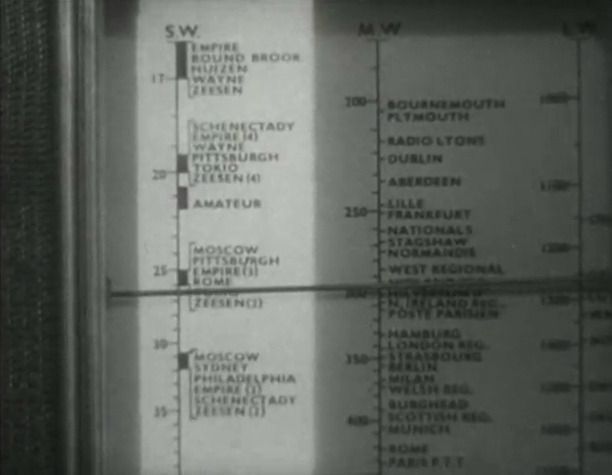

Freedom Radio

It all happening

there, where one is a leading specialist treating Hitler’s flaming

throat, and the wife is a leading stage actress (Iphigenia, no less) named to a

high government post amidst the tightening noose. “Now

I’m married to the Reichsdirector of Popular

Pageantry, I’m going to charge double fees.” The

very fine comedy of the opening stretches is a factor in Wyler’s Mrs. Miniver, the structure also may be

said to bear upon such a thing as John Osborne’s The Right Prospectus (dir. Alan Cooke) or Tom Stoppard’s The Romantic Englishwoman from the novel

(dir. Joseph Losey), but then it all really happened to Fritz Lang, after a

fashion.

The German

Resistance, a thing of old Heidelbergians to begin

with, whose annual New Year’s Eve reunion is closed down and one of their

number killed by the Gestapo. As in the days of the

witch trials, denunciations are a matter of jealousy and greed and blind

superstition. “I was there, I saw the look on

his face, he was enjoying himself!” The charm of the New Order lies in its lying,

Nietzsche’s “homage Vice pays to Virtue.”

Merely a question

of politics at first to which one laughing pays no heed, then of goosestepping SS men in one’s street (“probably

make you very fit”), then a “very becoming” new black uniform

on the young brother-in-law, formerly a painter, and then the murder of a

priest in his subsequently smashed-up church, only the beginning of a

thousand-year Reich.

“That’s

sheer treason,” says the wife, “I won’t listen to it.” Simon Gray in Butley

(dir. Harold Pinter) remembers the doctor switching his work lamp off and on

after she leaves for Stuttgart and her official duties. “The

intellectual blackout is complete,” says the good doctor in his first

broadcast to the nation. A fireside chat from a different

locale each night at 10:30 with the Gestapo hot on the beam. “If

we follow a madman, we are madmen ourselves, and we are doomed.” Popular pageantry means stadium rallies and

forty-foot banners in wind supplied by “our good doctor” Goebbels. In Berlin on a narrow sidewalk with a wide policeman, one

steps into the gutter and goes around him.

The astounding

construction pivots on a woman’s vanity table and an actor’s

dressing room, and then Chaplin’s The

Great Dictator (cf. Capra’s

Meet John Doe, whence perhaps the

entire misprision of Andrew Sarris in The

American Cinema). It comes down to three days

before Poland is invaded in back of a lie, that and the vision of one returning

from the concentration camps. “Karl, what have

they done to us?”

“Not us,

everyone.” Homage to Foreign Correspondent (dir. Alfred Hitchcock). “You

cannot escape responsibility by blaming it on your leaders, if you allow this

thing to happen the blame is yours and you will earn the loathing of posterity!” Wyler remembers the bullet holes (Penn too in Bonnie and Clyde), Cartier the deceptive

homeliness (also from Hitchcock) in 1984,

Pollack the essential structure down to the bullet holes in Three Days of the Condor, the grandeur

and precision of feeling expressed with quintessential reserve are certainly

English, even American according to Ford Madox Brown,

“both of us true inheritors from the Norsemen of Iceland, whose ladies

would take horse and ride for three months about the island, without so much as

a presumptuous question on their return from the much tolerating husbands of

the period.”

T.M.P. of the New York Times, “although there is an

undeniable amount of truth in what the film has to say, it is blunted and made

implausible by the lurid accumulation of atrocities on the heads of the Gestapo” (as A

Voice in the Night “at the Globe” in May of 1941). Daniel Etherington (Film4), “Second World War era

propaganda”. Radio Times, “wartime propaganda

drama.” TV

Guide, “typical wartime propaganda”. Sandra

Brennan (All Movie Guide), “WW

II propaganda film.” Halliwell’s Film Guide, “flagwaver.”

Quiet Wedding

In the village of

Throppleton, among the smart set of businessmen with country houses.

Minnelli later on

takes a pointed view in Father of the Bride, Asquith is an all-rounder

who follows the course of events somewhat more dispassionately, a central organized plan reveals itself as the wedding

materializes from a cricketer’s halting proposal to a general

mobilization of womenfolk abetted by the men.

The jokes are

very swift and keen, at last by the grace of God the

couple are hitched.

The reason for it

all is in three parts, on good feminine advice the polite groom abducts the

nervous bride in her father’s motorcar, passing the groom’s father

on the road at a good clip the latter is all but sideswiped, he shouts after

them, “lunatic!” The son, not recognizing

him, of course, shouts back, “idiot!” This

Œdipal gag is followed by a chaste night in the new flat (power not on), a

road accident and a session with the magistrates, “old baskets” as

they are.

Even this only

adds to the swelling hilarity resolved at the altar.

Five times

production was halted by the Blitz, says T.M.P. of the New York Times in

a rather glowing review.

Cottage to Let

A brilliant

screwball comedy laid on in Scotland at an inventor’s digs. A Spitfire pilot drops in by parachute, he’s a Nazi

spy. A Nazi spy coordinates the kidnapping of the

inventor, he’s with M.I.5.

It begins,

typically, with a misunderstanding. Is the cottage a

military hospital, a home for evacuated children, or indeed to let?

Very choice performances, and a dicky bombsight over 9000 feet, plus a

charity bazaar and an old water mill on a loch.

A Welcome to Britain

A truly inspired

masterpiece that is merely a job of work for the Ministry of Information

“with the assistance of the U.S. Office of War Information” on

behalf of the War Office to let G.I.s know where they

are, which is a pub, a home, a school, a railway station, a taxicab, a hotel, a

training camp, a ship, the enemy coast.

Co-directed with

Burgess Meredith, who talks to the camera in uniform throughout, score by

William Alwyn.

We Dive at Dawn

The Drake motif

carries right through, the Sea Tiger’s

steady captain has a butler of that name who arranges luncheons and soirées

with various “aunts”, the raid on occupied

Denmark and the Jolly Roger flown upon the submarine’s return generally

express it.

The crew are

married unhappily or betrothed reluctantly or vying for a girl, the voyage has

been uneventful, they’re given a new assignment.

The captain

musters all their forces for the sinking of the Brandenburg.

No result is perceptible,

the depth charges burst, the submarine leaks, lies

doggo, rolls over and plays dead.

Then the raid for

supplies, home and dry.

The Demi-Paradise

Olivier’s

great foreigners, this one cousin to the Italian balloonist in Saunders’ Conquest of the Air and the French

trapper in Powell & Pressburger’s 49th

Parallel. The sea route of Bacon’s Action in the North Atlantic or nearly,

then he comes over, in retrospect. “It all starrrted in 1939.” Not

Keats’ tourist, Eliot’s Stranger. English

boarding house. “All modern conveniences.” Hyde Park, Speakers’ Corner, where Shaw

delivered his reviews. A revolving stand of postcards,

for visitors. Will Hay, Paul Muni,

Olivier...

He’s got a

screw, for breaking the ice. Big business in Britain,

her father and grandfather. “Thou wast not borrrn forrr death, immorrrtal birrrd.” It needs work, that

screw. “I still say it’s very

revolutionary.”

Ian Holm has such

another Russian in Poliakoff’s Soft Targets (dir. Charles Sturridge). Behind the scenes at the pageant of English history (he

yawns).

A romance in two

parts. 1940, Europe gone, England besieged. The Battle of Britain. A

broadcast on the BBC, cello and nightingale, searchlights. Shipbuilding. The casting of the great screw. Germany

invades Russia. Churchill addresses the nation.

The pageant in

aid of his native city (he applauds, laughs at himself). “The

International” must be played, the pageant mistress discusses it with the

bandmaster in uniform and a couple of lady Britons of old and John Bull. Britannia with drawn sword sets the maiden free. The band, like Stravinsky and Diaghilev, settle on

“Song of the Volga Boatmen”.

The screw is

subject to metal fatigue in tests. He begins to

appreciate a music hall jest. It might be George M.

Cohan, Little Ivan Ivanovich,

“remember me to Nevsky Prospect.” The

inspiration in a cup of tea. “Well, that’s

that,” a bit of extra work at the shipyard is all.

No Highway

(dir. Henry Koster) remembers this. Laughter and

freedom are not equated, but “there is no laughter where there is no

freedom.”

Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times had no use for

it, English and all, “limp and dampish”. Variety was overwhelmed but praised

Felix Aylmer, “would excite risibility in a mummy.”

Time Out Film Guide,

“very cosy it all is, too.”

Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“pleasant, aimless” (Richard Wilmington thought he was being

condescended to, qua cinemagoing Englishman).

Fanny by Gaslight

The death of a

prosperous panderer to gentlemen, at the hands of a drunken bullying lord. The suicide of a cabinet minister who has ruined his life

through filial piety. The wounding of his assistant in

a duel with the cur. It ends in France, where another

duel was taking place.

Critics seem

generally to have objected to this on various grounds. “Simple,

obvious, hackneyed” (Punch). C.A. Lejeune for the New York Times simply reported from

London that “the customers love it because so many dreadful things

happen”. Variety found fault with the

editing and the tempo, and would have had “all the bawdy-house

sequences” excised. These viewpoints recur in

subsequent reviews.

The Way to the Stars

Basil Wright

noted the overture at the abandoned air station,

Resnais emulated it in Nuit et brouillard.

The marriage

token, a lighter, changes hands but the new man has jitters.

The excellent

poems are “Missing” and “Johnny in the Clouds”, expressing the idea.

The Winslow Boy

A five-shilling

dismissal from Royal Naval College goes at last to trial on Magna Carta.

Before he got to

the main English system he employed in The Browning Version, Asquith

still had the complicated variant of Hollywood lighting he uses here. The very intricate screenplay carries the drama in set-ups

put together by him and his actors that render a series of precise accounts.

A great price is

paid by Winslow père and the family, even the barrister (Robert Donat in

one of Asquith’s extraordinary leading roles), but the weight is lifted

at the last.

Neither Time

nor the New York Times had any patience with the film.

There was a bumper crop that year, or BAFTA would certainly have awarded

Best British Film and Best Film from any Source.

The Woman in Question

A

perfectly-turned item, gem or brummagem as regarded by friends or lovers in the

light of an investigation into her death by strangulation with a silk scarf at

a seaside hotel.

A comedy

nonpareil, a Rashomon with a parrot in its cage saying “Merry

Christmas”, rather placidly admired by Bosley Crowther in his

professional capacity as the film expert of the New York Times, but

really far above rubies in price.

The Browning Version

His translation

of the Agamemnon, “flawed” saith our hero “the Himmler

of the lower fifth,” whose own youthful and unfinished version in rhymed

couplets is preferred by an admiring pupil.

An amazing screenplay,

that might veer out of its way at any time and represent Nabokov’s Pnin

or Albee’s George, but doesn’t.

After wasting his

whole life and everybody else’s, Rattigan’s schoolmaster is made to

say “I’m sorry”.

Asquith is so

keen on the subject that his direction is said to be invisible, but a quick

glance shows his distinctive lighting in full sway.

The Importance of being Earnest

The two

characters are Algernon Moncrieff and his older brother Ernest John Worthing,

known as Jack.

Algernon’s

sport, Bunburying, consists in having a sick friend to call upon whenever

social responsibilities are too pressing. Jack, that

is Ernest, is always able to depart from the exclusively

“high-toned” demeanor expected of him as the guardian of a pretty

ward by going into town after one of his wicked younger brother’s

escapades.

There is no

friend, no brother, Jack and Algy do not know until the last scene that they

are related.

That is the simple,

evident structure. There is a great deal of

superstructure required to sort the mess out, and while this is of signal

interest, having two or more themes in counterpoint (the attractiveness of the

wicked, the very title of the play, etc.), it is generally distributed along

the lines of respectability or seriousness or earnestness in love, and even for

Lady Bracknell a young girl’s fortune is an earnest of her

marriageability.

The play has had

many critics who, like GBS, do not think it is important because they do not

see it is earnest. That, and not Asquith’s

direction, is the main reason why some reviewers have balked at the film in the

very terms used by Shaw on the opening night. “It

amused me, of course; but unless comedy touches me as well as amuses me, it

leaves me with a sense of having wasted my evening.” And

yet it is a very touching play, the two brothers, the handbag, Miss

Prism’s three-volume novel, the two girls of town and country, Canon

Chasuble, and (in Asquith’s film) Lady Bracknell riding the rails.

The Net

General security,

check check doublecheck,

safety of the central figure, hamstringing his best work (Arrowsmith, dir. John Ford).

Triple-fast

supersonic aircraft, the M7 prototype, future in

space.

The peculiar

constellation of its early piloted tests.

From the sea like

Mitchell’s seaplane (The First of

the Few, dir. Leslie Howard) to the stratosphere at a very pure diagonal. Danger of G forces, pressurized suits, a traitor in high

places.

A very fine

thing, achieved by Asquith precisely after the initial crisis is resolved as

suborbital flight (X-15, dir. Richard

Donner). A certain debt to Breaking the Sound Barrier (dir. David Lean) is gladly paid.

The absorption of

the work, a groundling’s love, the young lovers of Things to Come (dir. William Cameron Menzies), administrative

difficulties, a self-serving ally.

Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times, “wholly

incredible”. Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “quite adequately presented.”

R.J. Minney, Puffin

Asquith, “many believe” the director was miffed.

Desmond Dickinson

cinematography, Benjamin Frankel score, William Fairchild screenplay, from the

poet of The Way to the Stars.

The Final Test

England v

Australia, an American at the cricket. “He’s

come up in the batting order.”

“And down

in the age group.”

Rattigan &

Asquith record the moment of inspiration in a poète de dix-sept ans,

“I’ve got it, I’ve got it—or have I?” Pinter’s Hutton. “By

kind permission of the Third Programme...”

“Did you

know they were televising Turtle

tonight?”

“No, were

they?”

“You’re

sacked!” The author of Follow the Turtle to My Father’s Tomb on “Chekhov and

cricket...”

The American,

“I beheld today an astonishing spectacle, it was no less than the

personal Dunkirk of an aging cricketer, but a crowd of many thousands with the

wildest enthusiasm hailed it as his greatest triumph, no less,” a Senator. The legend and the fact.

A.W. of the New York Times, “definitely adds

up to fun.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “flat”.

Rattigan’s

screenplay of Goodbye, Mr. Chips

(dir. Herbert Ross) is certainly a consequence of these researches.

The Young Lovers

A firm basis on

the Odile/Odette theme for The Tamarind

Seed (dir. Blake Edwards), The Human

Factor (dir. Otto Preminger), and The

Russia House (dir. Fred Schepisi), not to mention Romanoff and Juliet (dir. Peter Ustinov).

Asquith has

Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps for

his pivotal turn in the last act.

Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times

(“beautifully directed... nicely acted”) found “very poor

common sense” (as Chance Meeting). Variety,

“under Asquith’s polished direction, the two leading players bring

a genuine freshness to their roles and give point to the arty touches used by

the megger to bring home the sensitive side of the

story.” TV

Guide, “good Cold War romance”. Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“quite nicely put together”.

Carrington V.C.

The greatest

tribute to Capra, a translation of Broadway

Bill (or Riding High) into the

Royal Artillery, thus acknowledging the transformation of Job into It’s a Wonderful Life, the Gospels

into Meet John Doe, etc., an artistic

tour de force (the U.S. title is Court Martial).

Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times, “a

judicial issue of trifling consequence and of no significance whatsoever to the

turn of events in the world.” Variety, “a subject of dramatic

intensity.” Time

Out, “lacking only the final ounce of sheer cinematic flair.” Leonard

Maltin, “a solid drama.”

Hal Erickson (All Movie Guide),

“witty... classy”. Halliwell’s Film Guide, “good... convincing...

serviceable”.

Orders to Kill

Liquidation of a

wayward asset in Paris under the Occupation. It’s

an American job, the French are losing operatives, the British help train a

Yank for it, a fighter-bomber pilot grounded after fifty missions. One hundred masterpieces are contained within this

framework, the finely articulated structure proceeds notably by steps, now one

thing, now the next, a prismatic, kaleidoscopic thing, ultimately.

Bosley Crowther

of the New York Times simply

couldn’t follow it, “this promising melodrama loses steam and

credibility”. Time Out, “a way above average Asquith film.” Leonard Maltin,

“low-key psychological study”. Halliwell’s Film Guide,

“strong, hard-to-take but well made”.

The Doctor’s Dilemma

The elephant and

the blind doctors, Jesus and the doctors, anything but a satire of the medical

profession, which is what Variety and Bosley Crowther of the New York

Times took it for, the latter most enjoyably, what was that deathbed scene

for, he wanted to know.

The vehement

satire of critics and academics and people who give awards and grants to save a

Blenkinsop because a Dubedat only makes them think of James Joyce’s

gentle lady, “she said her name was Dubedat, and then she did,

bedad!”

The nasty

business of picking up the widow afterward is handily taken care of, she

marries a collector of great pictures, in honor of her husband’s memory

and wishes, cf.

Jacques Becker’s Les Amants de Montparnasse (Montparnasse 19).

An out-of-date

play, Variety thought.

Libel

Television is a

central motif of this composition, and Asquith modulates toward its neutral application

of light to prepare his great effects at the close. He

also abates composition after giving a handful of sharp angular inset views

early on (and the silhouette of a stopped train filling the screen in a

flashback, with escaped POWs hiding beneath it, and a German soldier peeking

between the cars).

Bogarde

effectually shows a transition between his dual roles (one of which is an actor

standing before his mirror), making possible his dubious identity at the trial

when a third avatar is introduced.

Beneath the legal

metaphor is a military one, the victor only being decided when his

consciousness returns, availing him a memory of the attack and his proper defense.

The game is

played with tricks, ruses, feints and guises, such as the baronet’s

American wife, the Canadian smelling out a fingerless villain (The 39 Steps),

the terrible revelation of the hospital patient known

only by his bed number, Fifteen, and the superb jockeying of Bogarde among his

characterizations.

This is a great

working–out of cinematic problems to achieve a great abstraction, the

victor’s guilt resolved, before the ultimate refinement of

Asquith’s later films, and in fact something like the yellow Rolls-Royce

is visible in the car dealership scenes.

The Millionairess

A very brilliant

analysis of the essential problem. Capitalism has its

gifts, socialism its considerations, there is a modus vivendi and still

more, each in its way is most humorously unsatisfactory as a mere instrument of

human will, life does not follow such absurd programmes.

It is easy to

build a hospital for the poor and a factory to replace a sweatshop, but

humanity is strangely not served by such things always, in every way. And where is the man of science without money to command?

Wolf Mankowitz

arranged this out of Aragno’s arrangement of Shaw for a clear picture,

completely irresistible. Film critics, if one may be

pardoned for putting Bosley Crowther on the spot in his New York Times

review, have scarcely seen it at all.

Variety did not give itself the excuse of being distracted

by Sophia Loren’s charms but took a thoroughly professional view of the

film and came out considerably ahead.

Peter Sellers has

the “annual dinner at Romano’s” number to let you know

“who you are dealing with.”

Guns of Darkness

A coup d’état at the presidential

palace of Tribulacion, banana republic.

A “new

boy” with Napier International Plantations, chafing at the collar. “Be different,” says his French wife, the

winegrower’s daughter, “please, try!” It

gets to murder in the street next day, New Year’s. “There’ll

be a trial, of course, in the sports arena.” The

liberal regime, lately ousted by the army, falls into his lap (Richard

Brooks’ Crisis, John

Huston’s Under the Volcano).

All over by

Christmas, so to speak. “Look, I’m

English, um, you saw the flag.”

It’s the

interstices that tell the tale of company wives and the boss.

“You have such wonderful manners, Hugo.”

A pure source of

Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs. A complicated impressionistic set of fragmentary images

quite in Asquith’s line that, having undertaken the thing for whatever

reason or none, must come to terms with political quicksand as that and nothing

more, for example. Hard brutal facts are another

feature of the landscape, politically speaking, such as a whitewashed wall for

instructing villagers who “may not have heard the good news of our

revolution.”

“Another

job bitched up, is that what you were gonna say?” The war with its strange bedfellows, an end to

bosses of a certain kind (cp. Things to

Come, dir. William Cameron Menzies).

By John Mortimer

from the author of Furie’s The

Naked Runner, cinematography Robert Krasker,

score Benjamin Frankel.

New York Times, “familiar terrain”. Variety, “director Anthony Asquith

is slightly off form with this one.” Time Out, “there is, in fact,

rather more to it.” TV Guide, “too many implausibilities.” Eleanor Mannikka (All Movie Guide), “may wear too many hats

to be identified as either an

adventure, a treatise on non-violence, a psychological study, or whatever.” Halliwell’s

Film Guide, “a few tiny

comments about violence.”

The V.I.P.s

Crœsus times

three and the Duchess of Brighton (Margaret Rutherford) plus a gigolo (Louis

Jourdan) at London Airport.

Max Buda (Orson Welles)

the Yugoslavian film director has an Italian starlet (Elsa Martinelli) in tow,

his next film is Lessing’s Mary

Stuart but she shan’t even play Elizabeth. He kisses his elderly

accountant right on the lips for devising a tax dodge that will save him a

million pounds sterling by leaving England before midnight.

Les Mangrum (Rod

Taylor) the Australian tractor manufacturer has to be in New York this

afternoon or lose his company to Amalgamated Motors.

Madame Andros

(Elizabeth Taylor) is leaving her enormously wealthy husband Paul (Richard

Burton) for the gigolo.

The Duchess has

accepted a job at a Miami hotel as Assistant Social Directress, to save her

home.

Fog closes the

airport.

Andros threatens,

bribes, and writes a suicide letter.

Mangrum’s

secretary Miss Mead (Maggie Smith) encounters Andros in the writing room of the

airport hotel lobby, he gives her a blank cheque.

The accountant

hits upon another dodge, marriage to the starlet for one fiscal year, and gets

another kiss.

The fee for six

weeks’ shooting at the Duchess’s home means she doesn’t have

to fly to Florida.

Madame Andros

also stays home.

Beautifully

written, acted, and filmed.

The Yellow Rolls-Royce

The film proceeds

along a revolving formula, let us say, and doubtless with reference to Renoir’s

Le Carrosse d’or. The Englishman sells it after his French wife

dallies with a Foreign Office underling in it. The American gangster sells it

after his moll dallies with an Italian photographer in it. The rich American

widow ships it back to America after a dalliance with a Yugoslav partisan in

it, just before America enters the war.

That this

structure, in the lapse of time conveyed, could have any significance beyond a

plush ride in a finely-appointed automobile does not seem to have occurred to reviewers

in the general run of things.

England between

the wars, Italy under Fascism, World War II.

Thus the

modalities, which absolutely escaped A.H. Weiler of the New York Times, to be specific.